By Anand Manikutty

Here are some questions that often come up for second generation members of the Indian diaspora: how much should I relate to India, the country of my ethnicity, as compared with the country of my birth? How much should I relate to Indian culture? Should I relate to it at all, or choose to become — what has been called — completely “whitewashed”? Conversely, is it okay for members of the Indian diaspora to use Indian culture as a punching bag for all of their life’s frustrations and failures?

These are obviously important questions from the point of view of second generation and third generation Indian-Americans as well as other hyphenated Indians. Now, this is not something that can be fully addressed in the circumscribed space of a food column. However, we would like to tackle these questions in this column in a limited way and this will be purely from the point of view of food. I would argue that it makes sense for members of the Indian diaspora to connect back to their roots, at least in terms of food, but this is only if they wish to. We would also like to make the case that this process does not have to be hard. It can actually be quite easy.

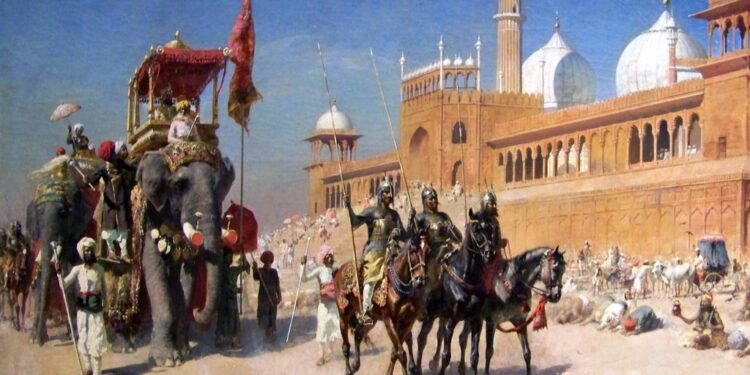

Before I provide a more detailed answer to the questions posed, let me introduce this food column itself. This is a food column that will feature recipes from the royal kitchens of India. Some of the recipes are reputed to go back to the medieval period. I will be writing this column in association with Amita Roy, a historian of India specializing in Indian Royalty. I will be writing the first two or three columns, and exploring these questions from the point of view of an economic historian, after which Amita will be joining me. Since the medieval period of India featured both Hindu and Muslim rulers, we will be presenting recipes from both Hindu and Muslim royal kitchens. Muslim kings contributed to Indian culture not only through their food, but also through their beautiful monuments and mausoleums. A section from the painting “The Great Mogul and His Court Returning from the Great Mosque at Delhi” by the American artist Edwin Lord Weeks is reproduced here. The Islamic influence in the architecture is, of course, evident.

So, let us go back to my original set of questions: How much should a Pravaasi Bharatiya relate to India, the country of their ethnicity, as compared to the country of their birth? How much should he or she relate to Indian culture? In a recent email exchange with Ghee Bowman, a British historian with whom I also conversed recently, a member of our team brought up the following additional question: “Why do Indians eat Indian food?” Also, we may ask: “Can we help improve their health outcomes by helping them make some fairly small changes to their diet?” A seemingly innocuous couple of questions like these can help us think about what we are eating more critically, why Indians seem to be particularly susceptible to diabetes, a lifestyle disease, and how our food choices may affect our health. We should perhaps also add an additional question to the mix: les Indiens en Inde devraient-ils manger des aliments de la cuisine indienne? Or if you prefer Hindi: kya bhaaratiya logon ko bhaarat ka khaanaa hee khaanaa chaahiye? Translated: “Should Indians eat Indian food?”

We would like to answer all these questions in the space of this column, but first, we would like to make a brief segue to the third century Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna. Nagarjuna is widely considered the most important Buddhist philosopher after the Buddha himself, and one of the most important figures in Indian philosophy. Nagarjuna was recently on my mind, and it is for the following reason.

I was recording an audio podcast series on Financial Independence and Professional Success in which I was talking about Josh Kaufman’s book “The First 20 Hours – How to Learn Anything… Fast”. Kaufman talks about how one can learn things fast, and proceeds to demonstrate how one can do it for six different subjects and skills. The subjects or skills that he chose were programming, yoga, touch typing, playing the Ukulele, windsurfing and the Japanese game Go. It was then that it occurred to me that two of these subjects actually lend themselves to iterative learning: the first is programming and the second Yoga. It makes sense that programming can be learned iteratively since one can sequentially gain an understanding of the different parts of any engineered system to understand the whole, but what about Yoga? What is noteworthy is that modern Hatha Yoga Practice seems to have been deliberately designed to be “learnable” in an iterative fashion. This seems to be also true of certain concepts in Buddhism and, indeed, the Buddhist scriptures themselves. What Nagarjuna observed is that there are both easy routes and difficult routes to understand Buddhism, but both reach the same destination.

Now, you might ask what the connection between Yoga, Buddhism and Indian food is. Well, the connection is this. You see, the great thing about Indian cuisine, both North Indian and South Indian, is that you can learn the basic concepts iteratively. Just like Yoga and Buddhism.

You can just learn a few basic ideas and nothing more. Then, as you learn more and more of these concepts, you just get more and more sophisticated in your understanding of Yoga, Buddhism and Indian cuisine. Let us see how it is with Buddhism. You can learn about Buddhism by first simply understanding the concepts behind the Four Noble Truths, the ideas of anicca, anatta and dukkha, and nothing more. But you can, if you like, add on to your knowledge by building upon these foundational concepts iteratively over a longer period of time. As you learn more and more, you become better and better at appreciating not only the philosophy of Buddhism but also Buddhist philosophers. The same is true of Yoga. You can, if you like, just get a very basic introduction to Yoga – for instance, via Josh Kaufman’s book. But if you want, you can learn more and more about Yoga, while all the time building on your prior knowledge.

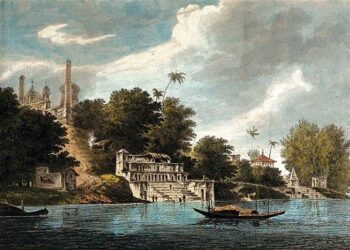

There is a certain beauty in what I would dub the Knowledge Architecture of both Buddhism and Yoga – a certain step-by-step building up of ideas upon ideas – that you find common also to Indian cooking. In this column, we feature cooking from the Royal kitchens of India, both Hindu and Muslim, and the theme of Islamic culture has been featured in this month’s column. This is evident in the pictures we have used here, including the one of the beauteous Taj Mahal.

Let us now go back to the original question posed. How much should members of the Indian diaspora relate to Indian or, to use the more appropriate term, Indic culture? Our answer to this question is that it is really up to them. At the end of the day, how much a member of the Indian diaspora relates to India’s culture cannot be decided for that individual by anyone else.

It is, however, worthwhile to keep in mind that scores of Indian-Americans, Indian-Australians and other people of Indian heritage have researched the diverse cultures of India fairly deeply, and found the ideas in there compelling. Besides that, the ideas of this column are based on science and have been shown to help people lead healthier lifestyles and even address such diseases as diabetes. While these sorts of approaches are clearly beneficial from a public health perspective, it is conceivable that these ideas are not sufficiently appealing or compelling to certain members of the diaspora who, as we know, just happen to be of Indian ethnicity. Perhaps, it is not sufficiently appealing for them to make these approaches a part of their lives. That is okay. There are just as many people who are not of Indian ethnicity who appreciate ideas from Indic culture and, of course, Indic cuisines, as we also have discovered throughout a panel discussion series I am running in parallel.

When we look back at the history of India, we, of course, also encounter the British. But since the British never considered themselves citizens of India, we will not be featuring British cuisine made in India. Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education and the Macaulay education system he helped introduce has been rightly criticised for its liquidating effect on indigenous culture of India. But anyone who has seen the beauty of Mughal Era Art in its monuments, mausoleums and miniatures would be inclined to think that here was a culture that was sophisticated and refined, and that cared about aesthetics as much as any other. With a view to capture this, we are also planning on preparing an e-Book for the Kindle which mixes and matches Mughal Era art with recipes from royal Indian kitchens with the help of an A.I.

As important as learning is, equally important are the learning organisations that members of the Indian diaspora are a part of. Even if they are somewhat loose or unsophisticated in their understanding of Indic ideas, as may be apparent from the work of some Indian-Americans on blogs such as Sepia Mutiny , it is their responsibility to make sure to correctly understand various aspects of Indic culture as and when they become part of learning organisations in the United States and elsewhere. Note that I will be only looking at things from the point of view of food. Other important questions of Indian history such as whether Aurangzeb was a good ruler, whether Babur should be considered a Central Asian or an Indian or even whether Aurangzeb was a 16th century Borat, will not be covered here. These deliberations we personally will leave to the able hands of the members of the Epimetheus Society.

When I read some of the articles on India in blogs by well-known Indian-American bloggers or view some of the videos on Youtube even by such celebrities as Russell Peters or Lily Singh, I wonder how they could get things so wrong. For instance, when Lily Singh questions the very idea of “holy water”, she is inadvertently rejecting a concept that has been shown by medical research to help address psychiatric diseases. But I could give her a pass for that. Less forgivable is her using Punjabi culture and Punjabi accents to characterize all Indians, for instance, in her video on Indian weddings. You never see a video where a comedian jokes about common characteristics of European weddings while all the time talking in an Italian accent.

The great thing about Indian cuisine, both North Indian and South Indian, is that you can learn the basic concepts iteratively

Here is another example. Russell Peters once said in one of his standup performances that Indian people and Chinese people cannot do business together, thereby trying to negate and whitewash something like at least fifteen centuries of history. As I was telling Prof. Deepshikha Shahi at the University of Delhi, these two countries have engaged in trade for tens of centuries. Indeed, there are probably few better examples of countries with different cultures which have, in fact, engaged in trade over tens of centuries.

There is real harm being done insofar as stereotypes are being created. It takes only a few days for these videos to go viral and stereotypes to take hold worldwide. But it takes months of work to put some of the false ideas to rest. There is a real problem of Information Asymmetry here. Through these means, the very knowledge systems of the subcontinent and other parts of the Third World are increasingly subjected to disruptive attacks, and now with the advent of Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, there is no way to easily police the disruptions to knowledge systems any more.

I say this quite conscious of the fact that some of these bloggers and vloggers now wield considerable cultural power as academics in the West or as online celebrities. So, there is a certain insolencia, Frechheit or chutzpah that one needs in order to question such “status quo ante’’ as may exist. And the fact is that there’s a certain “je ne said quoi” element that Sepia Mutiny (or SM) sorely lacked when it tried so hard to be a “sine qua non” of the blogging form.

How serious are these social media bloggers and Tweeters about their analysis anyway? I saw a post by a blogger on SM asking whether Barack Obama was a secret Hindu. I must admit that this thought had never crossed my mind before. I saw another blogger on SM make a post entitled “Babu hell” arguing against the NREGA Act. Now, this post seemed to lack any real economic arguments whatsoever. In this post, he questioned a very important and, from a national economic point of view, a very reasonable governmental program, viz., the NREGA, by questioning the national origins of Jean Dreze and Sonia Gandhi. Rather than argue for an economically viable alternative such as building toll roads backed by appropriate interests, which would of course be capitalist, he argued against the plan itself and closed the post with a vulgar reference. Does this not cause any reasonable reader cognitive dissonance?

“Say what? What does Jean Dreze being Belgian have to do with anything?”, may be your justifiable response. So, now, you, dear reader, are also displaying cognitive dissonance. One of the bloggers on SM, Amardeep Singh, seems to have solved his own cognitive dissonance on being a part of this group by posting on his own blog that he himself did not know economics very much. Maybe the post was unrelated. At any rate, there seems to be no clear response on this matter from another SM blogger Amitava Kumar either. If a tenured professor at an American university who has lifetime job security cannot be relied upon to police other bloggers in his own blog, or offer post facto explanations, then who on social media can, in fact, be trusted? Who else really can be expected to have this sort of time?

There seems to be no public policy debate in India that the Blogosophere, the Twitterosphere or the Facebook Metaverse does not make worse, as I remarked to the eminent economist Tyler Cowen recently, and this seems to be a failure of market-oriented economics or neoliberal economics. The NREGA Act, when it was announced, was roundly criticised on social media by many. Now, what exactly is the NREGA Act? The NREGA Act puts in place an employment plan. Among other things, it offers landless workers, day laborers, and destitute farmers, people on the very margins of society, some income in exchange for actual tangible work.

Given that this is work with real, tangible economically valuable outputs such as roads, and given that it can have potentially enormous effects on the lives of the poor, I had felt moved to speak out, but there has never been a way for regular people such as myself to do this with any great effect. Ironically, despite not having been born in America, I have found it easier to reach American economists and solicit their opinions or offer ideas on U.S. economic policy. Policy decisions in India, on the other hand, seem to be taken fairly opaquely.

Now, the truth is that for the vast majority of policy decisions, there is nothing in the analysis of the policy decision that requires any great secrecy. What is the big secret about where we are going with farm policy anyway? What is the big secret about what lockdown measures we are going to impose and when? All one needs is for the government to sign up to discuss things transparently on a platform. I myself have built an A.I.-based platform for facilitating exactly this sort of analysis, and have used this platform to great success in a Panel Discussion series I am conducting in parallel. I can make the software available for free. If you look at the past fifty years, there has seldom, if ever, been a need to enact policy in the entire history of any of the twenty-nine states of India or the history of the Indian State wherein a better policy could have been put in place by virtue of avoiding parliamentary debate or serious economic debate.

We in this country are spending too much of our time looking at the merits of this recent book by Wendy Doniger or that recent book by Audrey Truschke – much of the scholarly work from departments of South Asian Studies seem to deal with pre-modern India with practically zero impact on the economic lives of Indians today. With approval from the Presidents of the leading American colleges, this could easily change. If these departments can help drive discussions on issues of national importance, they could easily erase what bad blood these departments may have created in India over the past few decades. Just this one change – viz., changing the opaque nature of Indian policy making wherein policy decisions are not taken transparently and without appropriate critique by economists – would make a difference. Just this one change alone would significantly change the course of the Indian economy. Indeed, some of the poor economic decisions of recent vintage seem to have arisen out of the blind application of neoliberal economics.

In order to resolve these issues arising from the blind application of neoliberal economics, I have developed a new theory to explain global economics. This theory explains economic outcomes a lot better than Adam Smithian ideas. My dataset of interest is the global impact and distribution of diseases arising out of diet and pandemic pathogens, and the strategic management implications of the same.

Jared Diamond in his book “Guns, Germs and Steel” poses a question that he calls Yali’s Question. Yali, a local New Guinean politician, wants to know why “white people” had so much more material stuff whereas black people in New Guinea had little. My version of Yali’s Question concerns not why “white people” “developed” “so much cargo”, or material stuff, and why “black people” had “little” but why there is a certain distribution of malnutrition and disease in different parts of the world and questions such as why “black people” in certain countries have so much more burden of disease. I have developed a theory that offers a more realistic perspective on the world around this. This theory, that I call the Disruptive Dependency Theory, like the Dependency Theory of economics from which it derives its name, also argues that resources are transferred from a periphery of poor and underdeveloped nations to a core of rich and developed nations. It does not however blame any nation per se. It simply provides a disruptive account of the state of the world that is, in my view, a view that captures reality better.

Disruptive Dependency Theory and the Real Competitive Advantage of Nations

This novel theory, called the Disruptive Dependency Theory, is different in that it adds the following new ideas which develop the former theory further in the following way:

In addition to the core and the periphery, there is a third category of nations which have characteristics somewhere between the nations of the core and the nations of the periphery. A similar approach has been advocated before, but in this column, I will restrict myself to simply calling out Brazil and Russia as two such nations.

Furthermore, there is a fourth category of nations that within themselves are subjected to the disruptive change referred to in the name of the theory (more in that below). These are nations like India, which are large enough in size and spread out sufficiently in terms of geographical extent that there are regions within the country that qualify as the periphery and other regions that qualify as the core.

The theory also argues that countries at the core more or less deliberately disrupt democratically elected regimes in the periphery so as to increase their exports of defense technologies such as stealth bombers and advanced bombs. Since it takes thousands of man-years of agricultural peasants’ labor to manufacture even a single bomber, there is a net transfer of wealth from the latter to the former. The transfer of wealth, according to this theory, occurs not only via trade agreements and deals that tend to benefit the nations of the core, but also through four kinds of disruptions.

It is worth noting that the primary focus of DDT theory is not to advocate national policies at all but rather only policies and strategies for business and individuals. It is also worth noting that by advancing this theory, I myself am, in no way, bound to it. An individual can choose to not be bound by a theory as part of his ideological makeup. Just as an individual can advance Newton’s theory of Gravitation to explain certain effects, while being aware that Einstein’s subsequent development can also be useful to explain other effects, so can an individual do the same in economics. My goal is to simply advance evidence based, scientifically valid opinion. At the same time, I would like to note that I tend to be somewhat conservative in declaring the viability and value of my own new results.

With that out of the way, I would like to add that this theory has important implications for business school education. My (very conservative) analysis offers the conclusion that this theory and its implications ought to be taught in business schools as an alternative theory. Both Michael Porter’s Theory of Competitive Advantage and Five Forces Model need to be updated, per this theory. The argument that this theory should be taught as an alternative theory seems beyond reproach, and I see no intellectually viable argument against including it other than a refusal to look at models that don’t accord with one’s own worldview. Bluntly put, business school curricula need to be updated based on an understanding of this. I would like to add that this sort of a change to business school curricula has been needed for a very long time.

There are four main types of disruptions according to this theory, and these disruptions are the real reasons, according to this theory, for the Competitive Advantage of Nations. My area of expertise is Strategic Management, and thus, I will reference work in this field. I deviate from Michael Porter’s arguments on Competitive Advantage of Nations in his book of the same name. Furthermore, the theory shows that Porter’s Five Forces model is incomplete. We need to add two more forces to the Five Forces model, viz., Government and Pandemics. I propose in this theory four main sources of disruptions to economies:

(a) Disruptions due to Defense Technologies: this refers to the disruption of existing, mostly democratic regimes by the secret service agencies of certain countries in the core (e.g. the CIA), the monopolization of the development of expensive defense technologies by these latter “rich” countries and the subsequent export of these technologies to the periphery. These defense technologies are developed so as to help the countries in the periphery “guard themselves” against violent insurrection; however, this insurrection is, in fact, actually partly instigated by the rich countries of the core. Countries which have been affected include Pakistan, Syria, Libya and now, of course, the now infamous case of Afghanistan. The economic lives of the more than 250 million people who live in these countries are better captured by this theory than any other theory I am aware of.

(b) Disruptions due to Disruptive Innovation and Information Technology Platforms: the disruption of existing businesses by disruptive technologies such as via robotics-based and artificial intelligence-based technologies has been noted before. For example, the development of the technologies that make it possible to develop websites such as Expedia that disrupt existing travel agent businesses and autonomous vehicle technology such as used in Waymo that disrupt the economic lives of truck drivers, pizza delivery personnel and chauffeurs. This sort of disruption contributes to the existence of the fourth category of nations described earlier.

(3) Disruptions due to Social Media and Knowledge Based Technologies: the disruptions to existing institutions due to Social Media and Knowledge Based Technologies need no great introduction. Every day, there are people all over the world on social media questioning economic policies – both good and bad. Here is a point I would like to make here. What has been really remarkable is that, despite having moved to India from the United States, I am able to follow the state of thinking on public policy issues in the United States quite easily due to blogs, and remotely at that, but am unable to understand the state of thinking on important public policy matters in India. What one needs in India is a similar system of universities as they have in the United States with salaries that are comparable to salaries globally. If India offers a few economists seen figure salaries (in dollar terms), they could easily line up enough economists to look more seriously at issues such as whether lockdowns are necessary. These issues are Trillion Dollar issues, and the expenditure of a few million to save a trillion is really quite a bargain.

One example of the economic questions for India are on the new farm laws passed in 2020 around which there were recent protests by farmers. Another example is the question of whether we need stringent lockdowns at all for Covid. Instead of serious economists offering us their thoughts, we have celebrities telling us what presumably their gut instinct on any particular matter is. Although these celebrities wield enormous cultural power, it is clear that they do not have any responsibility for decisions taken and, furthermore, it is clear that their opinions will not add anything substantial to the debate itself.

We have turned the matter of national economic policy into a social media game reminiscent of medieval tournaments involving jousting knights with the rewards remarkably being worth nothing at all. The rewards are little more than Likes and Shares. Upon encountering this sort of irresponsible behavior, I want to say: “Hur vågar du?” Or translating from the Swedish, “How dare you?”

(4) Pathogenic Disruptions due to the development of Advanced Genetic and Transportation Technologies: The disruption of economies in the periphery is also due to the development of advanced microbial technologies such as gain-of-function technologies which lead to the creation of pandemics and endemic diseases, and the development of transportation technologies such as aircraft which transport pathogens around the globe. Contrary to popular belief, there is nothing new about pathogens disrupting economic activity. In fact, pandemic pathogens such as the Coronavirus simply lie on a different end of the spectrum as compared to pathogens causing diseases such as Caribbean dengue and malaria which disrupt economic activity in smaller, more circumscribed regions of the world. These areas of the world do not have powerful media agencies advocating for them. These technologies cause economies which manage to make economic progress or progress in terms of HDI indicators such as literacy to regress back and lose years’ worth of progress in the span of a few months. For instance, there is a non-zero probability that the Covid pandemic was one such exogenous shock to periphery economies around the world.

Adam Smith is rightly considered the Father of Economics. It was he who identified or, at the very least, popularised some of the ideas that we now consider foundational in economics. The main theoretical and extremely disturbing question the DDT theory raises is whether we are suffering from an anchoring bias in terms of how we view economic principles and the field of economics itself. In science, earlier theories are almost always more foundational and more fundamental. But there is little reason to believe that the same is true in the social sciences, especially in the field of Economics. In fact, in economics, one could argue that it is the later theories such as Marxism and Maoism and, I would like to add, the Disruptive Dependency Theory, which have more descriptive power. Also, in terms of economic models, perhaps, we are basing ourselves too much on Anglo-American models of growth at the expense of Scandinavian models of growth. In this column, I am not taking any position on these theories or models, but only claim that the DDT is a better descriptivist account.

The DDT is necessary to understand what has led to the prevalence of economic disruptions due to diseases such as Covid that we see around the world today. My chief concern is not to look at the distribution of wealth around the world. One significant critique of the neoclassical model of economics is that societies differ markedly in terms of how they perceive wealth. Some countries valorize and acclaim successful businessmen and businesswomen whereas, in other countries, such as some countries in South Asia until recently, successful businesspeople were rightly regarded with some suspicion. However, what is common to virtually all societies is that, at both an individual level and a societal level, almost every society without exception tries to avoid disease.

This theory not only explains the economic lives of people around the world today better but also explains the economic lives of people around the world for the past five centuries better. No one can deny that Adam Smith’s theories may explain the pin factory. And the lives of people attached to such pin factories as may be around England or India today. By way of contrast. it will be seen that the DDT explains something slightly larger – namely, the continent of Africa.

Also, explained are the economic lives of people today in the nation of Iran. And the nation of Syria. And the nation of Iraq. And the nation of Afghanistan. And the nation of Pakistan. And any more. And, in fact, the lives of people in the entire continent of Africa. Not to mention the continent of South America. Also, not to mention many areas of the Middle East. These continents and continental areas are somewhat larger, let us not forget, than Adam Smith’s pin factory.

An advantage of proposing solutions, however narrow they may be in scope, based on evidence-based medicine is that one can at least present people with choices in terms of the costs involved. A question on Quora from 2018 asks who the best columnists in India were. The answer according to this Quoran included the following journalists, thinkers and authors: Mukul Kesavan, Ramchandra Guha, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Swapan Dasgupta and Mihir Sharma. One must add to this list Pushpesh Pant, Ravi Shankar, Devdutt Pattanaik, Shashi Tharoor, Shinie Antony. And adding the reasonable assumption that everything in India must proceed along dynastic lines, we should perhaps add Ishaan Tharoor, Kanishk Tharoor, and perhaps even Shobha Tharoor Srinivasan to this mix. Their columns are certainly not lacking in literary quality. Mukul Kesavan seems to like cricket, and his enthusiasm comes through in his columns. Mihir Sharma seems to have a liking for capitalist economics, and has a range of opinions on everything from the vaccine inequality problem to the question of infrastructure development in Europe to India’s new industrial policy. Ramachandra Guha seems to have a taste for social issues and activism.

Now, let me tell you what I noticed after having moved to India after spending around twenty years in the United States. What I noticed is that, by way of contrast with American columnists, none of these columnists ever analyse any economic issue with a transparent account of the costs involved with various policy choices or offering their own estimates of costs. Not a single one of them does this. Not Mihir Sharma, not Mukul Kesavan, not Devdutt Pattanaik, not Shashi Tharoor, not Ishaan Tharoor, not Kanishk Tharoor, no one. So, why don’t we just hire Tyler Cowen or Alex Tabbarok at million dollar salaries to work on India’s Covid problem full-time once America resolves its Covid problems?

The Covid pandemic has been ravaging the House of India for more than eighteen months now, and there is no clear sense that evidence-based approaches are being used to look at the costs involved with various economic choices. The basement is flooding. Since Economics is no longer my main area of study, and since I don’t get paid to work in this field, you cannot expect me to be looking into why the basement of the House of India is flooding. I have been working on writing books and outlining ideas as an economic historian and have not been spending time looking at Covid. But, really, this is the job of professional economists.

Rather than kvetching about the situation, which a lot of people have already done, I also have the outline of a solution. What I want to ask is whether we could incentivise professional economists, such as Alex Tabarrok, Tyler Cowen or others, to help us look into pandemic related economic issues for India, and propose that we simply conduct economic discussions in the open on a tech-based platform to keep things transparent. While the Covid pandemic has been ongoing in India, Amartya Sen has written a book about himself. This allows us to conclude that Amartya Sen is the world’s leading expert on … Amartya Sen? What have Rakesh Khurana or Mihir Desai for that matter been doing? Desai and Khurana seem to be good at playing academic politics but not very good at solving real world problems. First in games, last in solving problems. If anyone should ever meet them, they should ask the latter worthies why no work on Covid has been forthcoming from them. It is arguably our lack of ability in India to control the games being played in American academia that has contributed to our economic failures owing to Corona. None of these academics seem to have done any significant work to answer the important questions facing a Covid-stricken India today.

In economics, incentives matter. But in order to incentivise this approach, India does have many strategic cards to play. It could, of course, incentivise people with money. It could also incentivise it with its awards, namely, the awarding of the Bharat Ratna, the Padma Bhushan, the Padma Vibhushan, et cetera. Why not award these honours to economists around the world who can actually help us solve real world problems? These economists don’t have to be of Indian origin. Economists such as Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabbarok by way of their blog Marginal Revolution, and economists such as Brad DeLong do seem to be looking at the issues surrounding the Covid pandemic and posting literally daily. They do seem to have a good handle on the Covid pandemic in the United States. Additional people, who will look at it through a different ideological lens, can be hired to validate their analysis so that transparency is, at all times, preserved.

This problem of lack of transparency is not a problem confined to the economic analysis of lockdowns for the Covid pandemic alone. This seems to be a problem all across policy in India. I should note that what I mean to imply is not that these columnists are incompetent. It is rather that such data may well not be available anywhere. But to continue to read about accent-shaming and Tom Cruise in the centre pages of the Sunday Magazine of the Indian Express while Covid rages on instead of a clear, ongoing discussion on the costs involved in the various policy choices for Covid seems bizarre.

To continue the House analogy, the basement for the House of India is clearly flooding. But instead of bringing in a plumber and proposing to reward said plumber appropriately, how would it be if we brought in a Film Studies major who can tell us whether she liked Tom Cruise in the latest movie and fixed our VCR instead? Or a linguistic expert who appraised us about the importance of not being classist and open to different sorts of accents, and fixed any issues with our Wokeness? Are we Woke enough yet? Because, you know, thinking about this question will fix all our Covid problems.

This is not complicated. It is about comparing costs. As I was telling Prof. Bhaskaran Raman at the Indian Institute of Technology Mumbai, if someone can present important policy questions as involving a set of Choices A, B and C, and present the estimated costs involved with each decision, one can expect the ordinary citizen to understand the tradeoffs involved better. It is really that simple. None of these leading columnists in India seem to do what a front page or centre page columnist really needs to do. And this is not a laughing matter. There is a real opportunity cost involved here.

This is really the Million Dollar Question facing India today. In fact, it is perhaps more accurately described as the Billion Dollar Question. There is a real opportunity cost for India in not channeling resources to help execute this sort of economic analysis and even for newspapers to give journalists not executing evidence-based analysis centre page space. And this opportunity cost is that good development ideas are routinely ignored, and bad development ideas are instead adopted.

Let us just take a couple of questions of economic policy, viz., whether lockdowns are needed in the face of Covid, and, if so, in what form; and whether schools should be reopened. Despite looking at this issue for over six months, neither I nor Prof. Bhaskaran Raman have been able to uncover any papers evaluating the costs involved with the various choices around lockdown. In fact, despite Prof. Bhaskaran Raman having written many opinion pieces on the reopening of schools, there has been no side-by-side comparison of the costs involved with the various choices available in his work. If just these two questions could be looked at transparently, that alone would make it all worth it for us. It would make all the work that our company’s team put in for the panel discussion, for this column and for the software mean something.

Okay, with that introduction out of the way, let me introduce the recipe for this month. This recipe is for a somewhat well-known dish of the Muslim Era in India called Murg Mumtaz Mahal, and it is from the kitchens of the Mughals. So, here without further ado is our recipe for this month.

Ingredients –

1 Kg of Chicken

4 qts. of Onion

150 g ghee

25 g Khoa

20 qts Cashew nuts

100 ml Curd

2 tbsp Red Chilli Powder

1.5 tbsp Coriander Seeds Powder

1 tbsp Salt

½ tbsp. Cumin

150 g Ginger

1 pinch Cardamom Powder

1.5 tbsp Lemon Juice

1.5 tbsp Kewda Water

10g Saffron

METHOD –

Step 1

Heat the ghee in a non-stick wok.

Step 2

Add the chopped onions. Stir fry until nicely browned. Remove into a dish and let it cool.

Step 3

Add the ginger pieces in the wok and stir fry until brownish. Remove into a dish and let it cool for a few minutes. Then, blend the fried onions and fried ginger into a smooth paste. Keep aside.

Step 4

Now, add the chicken (leg & breast pieces) in the same wok and reduce the heat to medium-low. Also, add the khoa (dried whole milk), red chilli powder, coriander powder, & cumin seeds. Mix well for 1-2 minutes.

Step 5

Pour some water (about ½ glass) and cover the wok for 15-20 minutes over medium heat.

Step 6

Next, uncover the wok. Add salt & curd. Mix gently and cover the wok again for 15-20 minutes over low heat.

Step 7

Add the cashew paste (cashew nuts soaked in water for 15-30 minutes and blended into a smooth paste). Also, add lemon juice, kewda water, cardamom powder (elaichi powder), and saffron liquid (saffron strands soaked in lukewarm water for 10-15 minutes). Mix well for a minute and cover the wok for 5-7 minutes.

Step 8

At this stage, remove the lid add the fried onion-ginger paste. Stir cook for a few minutes and cover the wok for 2 minutes over low heat.

Step 9

Lastly, turn off the stove, uncover the wok, and serve!

(The author is a strategic management expert, economic historian, poet, Indologist, and a computer scientist. Currently, he is the editor of Termite, the journal of the Epimetheus Society, Top Society and a couple of other High IQ Societies.)

(The author is a strategic management expert, economic historian, poet, Indologist, and a computer scientist. Currently, he is the editor of Termite, the journal of the Epimetheus Society, Top Society and a couple of other High IQ Societies.)