More often than not, discussions around Indian culture in the Western media tend to be biased

By Amita Roy & Anand Manikutty

In a previous column, we had mentioned “ghee” as an example of a food that entered our diets by a historical accident. Ghee is still extensively used in Indian cooking, but given that we now live in a modern consumer-oriented society, there is no reason why we cannot change this eating pattern, especially with all the new technologies that are now on offer. It is part of the Idea Of America itself to believe that the innovation we work on today will help make a brighter future for us and our children in the future. It is also an idea that animates this column.

We continue to discuss “ghee” in this column, and argue that it is part of a behavioural pattern that we must unlearn. But first, a note about the recipe for the series comes from Awadh or the area around Lucknow in India. It is called Musallam Raan and tastes quite delicious.

Back to discussing ghee. As discussed before, Ghee has historically been considered one of the best cooking fats in Indian cuisines for centuries. The reason for this, as we said, is historical. There have only been roughly a dozen large mammals that have ever been domesticated. Among the attributes that one looks for in a potentially domesticable species are the following: size, temperament, growth rate and diet. The cow was one of the larger animals that could be domesticated in Eurasia, and indeed is the one animal that meets all four criteria to the greatest extent. It, therefore, acquired a certain status that other animals did not.

This aspect of the nature of the adoption of the cow as a religious icon and the subsequent adoption of milk products has not been sufficiently appreciated within political and learning organisations within India. The advent of globalisation has made collective learning and organisational learning particularly important. As the Indian diaspora spreads across the world, it is important to take into account their cultural backgrounds when developing any learning solutions.

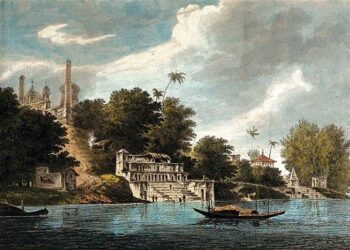

But still, notwithstanding cultural factors, while it seems clear why this ancient deference to the cow arose, there is no reason why such deference should be further preserved today in India’s special treatment of cattle of the bovine persuasion being allowed to walk around on Indian roads today. It is a sight virtually unique to India, and not something to boast about. And with that out of the way and in keeping with the theme of Awadh or Oudh, here is a picture by the 18th century artist William Hodges of a part of the city of Oudh.

In a paper published in the International Journal of Learning and Change, Prof Manikutty writes: “The steadily increasing degree of globalisation of enterprises implies development of many skills, among which the skills to learn are among the most important. Learning takes place at the individual level, but collective learning and organizational learning are also important. Learning styles of individuals are different and learning styles are affected by the cultural backgrounds of the learners. Organisations need to create conditions for effective learning at the individual, collective and organisational levels.” As has been mentioned before, Indian-Americans, Indian-Canadians and other hyphenated Indians have begun to use their cultural background for the purposes of entertainment, and certainly, what level of learning individuals display should be seen as dependent on the organisations from which they acquired their learning. Thus, even if certain members of the Indian diaspora such as Russell Peters and Lilly Singh have odd or confused things to say about Indian culture, it is important that we recognise the various biases with which they enter this discourse.

The fact that a lot of the discussion around Indian culture in the popular media is biased needs little introduction. Why does this happen so much? One reason for this is Eurocentrism. Let us look at an example. Why are Lilly Singh and Russell Peters more or less given a free pass if they say something wrong about an aspect of Indian history or culture, but immediately caught out if they say something wrong about European history or culture. (If Peters were to wonder whether Rome was in Italy or France, people would call him “stupid” or “dumb”. But he seems to have very little knowledge about the geography of India and that seems to matter very little.) Another reason for this may be the nature of social media. It may even be that Singh and Peters simply choose to essentially engage in a sort of disingenuous way knowing fully well that such an approach is likely to provoke more reactions online and, thereby, make them better known. A third reason may also be the state of schooling in their home countries, viz., the United States and Canada. Indian-Americans often use this as a defense of their own lack of familiarity with Indian and other cultures and that is understandable and forgivable. What is not condonable is to use that as a basis for getting more “Likes or “Retweets.” Given that the underlying population in question is itself not very knowledgeable, and this would be a global audience of Europeans, North Americans, South Americans, Australians and so forth, the wrong sorts of tweets get retweeted more and the state of disinformation on the Internet only increases. It is this dynamic that certain academics such as Wendy Doniger also seem to exploit. When they say something wrong about India, they simply label it as “provocative thinking”. Well, provocative arguments do have a place in society, but that should be done with the idea that said provocateurs should make themselves available for closer questioning. I have myself engaged with Prof Doniger and wanted to bring up a step-by-step critique of her book which claimed to undertake doing an all new history of the Hindus as part of ’s Panel Discussion Series. However, Prof Doniger turned down our request citing a reason that we, at Qwykr Technologies, refuse to accept as valid. As a counter response, I have used my good offices as the Editor of Termite magazine to charge a ten thousand fee payable by the University of Chicago or Wendy Doniger personally for responding to any reviews of the articles in our journal critiquing Wendy Doniger’s work.

Where does all this leave us? Most likely, it is a combination of both lack of knowledge and disingenuousness that causes much disinformation to spread via Social Media (and the truth is that one cannot hope to combat all of that with one panel discussion, but such panel discussions which employ innovative Artificial Intelligence technology are a start). It is our hope that this column will help reduce the disinformation on the matter of dieting, especially as it applies to health issues such as diabetes and obesity. With that out of the way, let us now view this beautiful map of the Awadh/Lucknow region by Letts, Son and Co. Ltd. who have published many other beautifully rendered maps of areas around the world including cities such as Berlin, Vienna, and Brussels.

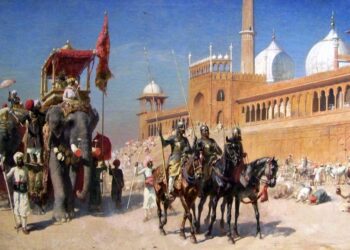

As we can see, Awadh is a region in the Northern part of India in what is now Uttar Pradesh. Before independence, it was part of an administrative entity known as the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Oudh being the British Era spelling of the Indic word “Awadh”. Okay, so back to our discussion. Here is one more example of Eurocentrism in Social Media. Lilly Singh in one of her videos makes certain comments about “Indian weddings” which includes her attempts at imitating or perhaps slightly mocking a Punjabi accent. It is, of course, odd to hear Lilly Singh characterise “Indian weddings” in this particular way. One does not expect comedians to imitate a German accent and say that this is what one may expect to hear at a “European wedding”. Similarly, one does not expect comedians to imitate an Italian accent while making comments about alcohol served at “European weddings”. Yet a certain amount of essentialisation has occurred in the blogosphere and the Internet about India. This has led not only to such positives as a greater understanding of Indian culture around the world, but also such negatives as certain sorts of stereotyping and negative characterisations and misrepresentations of Indians as “cheap”, “ and even “prone to rape”. The problem, from an economist’s point of view, is the problem of Information Asymmetry. With the introduction of that term out of the way, let us segue to take a look at a rendering of the Durbar of the Badshah of Oudh.

Now, that is a scene that as beautiful as any you are likely to see even in “Assassin’s Creed Chronicles: India”, a beautifully recreated depiction of 19th century British India. On that note, we conclude this month’s column. We will come back with the recipe for Awadh in the column for next month and continue the discussion on Information Asymmetry as well.

(Amita is a historian turned startup entrepreneur whose specialisation is on Indian Royal families and their luxury lifestyle. She is also a Research Fellow from Indian Council of Historical Research under Government of India and also an incubatee with IIM – Kashipur.)

(Amita is a historian turned startup entrepreneur whose specialisation is on Indian Royal families and their luxury lifestyle. She is also a Research Fellow from Indian Council of Historical Research under Government of India and also an incubatee with IIM – Kashipur.)

(Anand is a strategic management expert, economic historian, poet, Indologist, and a computer scientist. Currently, he is the editor of Termite, the journal of the Epimetheus Society, Top Society and a couple of other High IQ Societies.)

(Anand is a strategic management expert, economic historian, poet, Indologist, and a computer scientist. Currently, he is the editor of Termite, the journal of the Epimetheus Society, Top Society and a couple of other High IQ Societies.)