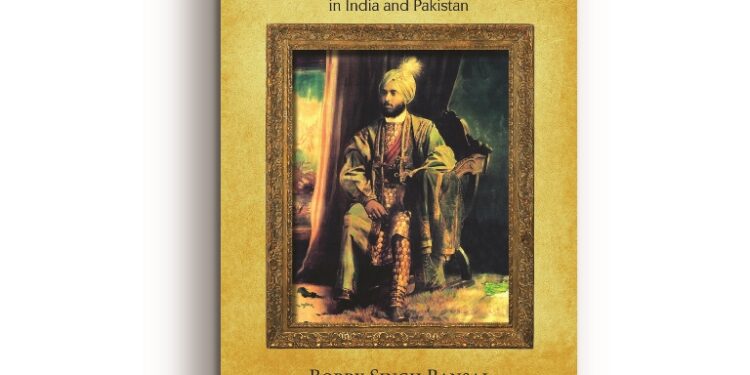

A look into undivided Punjab, the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, his court and courtiers, his wives and children, his descendants. A candid gaze at those in power and the life and times of a bygone era

BY H. KISHIE SINGH

The first impression of The Punjab Chiefs: The Lost Glory of the Punjab Aristocracy in India and Pakistan by Bobby Singh Bansal, a coffee table book, is impressive—with the colourful vintage photograph of a Punjab chief.

Bobby Singh Bansal, a councillor of Syston, a small town in Leicestershire, a county in England’s East Midlands, realised that Dalip Singh, son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was buried in Elveden, the Maharaja’s estate, and an hour’s drive from where Bansal lived. He wasted no time in visiting the estate and started to gather what material he could lay his hands on regarding Maharaja Ranjit Singh, his family, his generals, friends and courtiers.

Bansal set about searching for courtiers in the Maharaja’s court in Lahore during his reign and managed to trace descendants of those families in India and Pakistan. This exercise took him all of five years; after all, Lahore was the capital of the kingdom of the Sikhs and a cornucopia of information. Covering 65 ancestors of aristocratic families, a family tree of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the book stretches across three pages. Unfortunately, however, it is dated only until 2000.

At the recent launch of the India edition of the book in Chandigarh, Bansal admitted that the list was incomplete and that names could have been misspelt.

Extensively researched and a repository of knowledge about the families in the limelight in those times, the gap in historical facts is due to chunks of records remaining behind in Pakistan, and many others being unearthed from trunks where they were at the mercy of the weather and termites. Some prominent families with an incomplete family tree include the Sodhis of Guru Harsahai, the House of Bagrian and the Sandhawalias.

Despite this, it is a treasure trove of Punjab’s aristocratic times—a chronicle of the Sikh aristocracy from Maharaja Ranjit Singh to the present with mention of descendants like Bharat Inder Singh and Rani Jagdish Kaur of Fardikot.

Bansal admits the book is a continuation, or perhaps an extension, of the first edition of The Punjab Chiefs by Sir Lepel Griffin, published in 1865. Griffin’s book was followed by an updated version by Charles Francis Massy in 1890, and again by H.D. Craik in 1909. The author maintains, however, that his work is an “endeavour to correct and mend anomalies and inaccuracies in the 1865 edition of Griffin”.

It starts with the House of Maharaja Ranjit Singh simply because the “history of Maharaja Ranjit Singh is, in fact, the history of Punjab” in many ways. But instead of his political exploits the author focuses on lesser known facts about the wives and children of the Maharaja. “History has never really depicted an explicit account of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s wives and children. The book would be deficient without the inclusion of the Maharaja’s family, specially his lesser known sons,” says the author at the beginning. For example, very little is known about the Maharaja’s descendants like Kharak Singh, Prince Nau Nihal Singh and even Duleep Singh, who had eight children from his two wives.

Bansal underlines emphatically that the history of the Maharaja’s lineage has been distorted to satisfy accounts written by English writers. The account of Maharaja Duleep Singh is riddled with misinformation and half-truths. Equally baffling was that he was flooded with “numerous assertions and claims by relatives as descendants of the Maharaja. I have been inundated by many unscrupulous individuals in connecting their names with the Maharaja’s lineage, who, however, never provided me with any evidence to corroborate their fanciful claims,” notes the author.

There is mention of less important houses like Alawalpur, near Jalandhar, and Arnauli, which, aristocratic in their own right as local satraps, joined hands with the more influential houses.

A rich new dimension is added when the narrative shifts focus from Maharaja Ranjit Singh and family to the courtiers. And in the telling we have a glimpse of undivided Punjab and the private lives of the Punjab gentry. If we have the House of Ayudhia Prasad and the House of Akalgarh evidencing the shades of Hindu aristocracy, we also have the House of Kalaswale (Pakistan) underlining the Muslim ancestors of the Bajwas. The family of Diwan Ayudhya Prasad came from Kashmir to Benaras. However, it was his son, Ganga Ram, who made a name for himself, rose in social circles and ultimately joined the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and became a key person in his coterie. He would be the Maharaja’s ambassador for treaties and for liaising with foreigners.

The House of Akalgarh had its founder in Diwan Sawan Mal Chopra. His son, Lala Hoshnak, earned a respectable place for himself in the court of the Maharaja. His services were largely used by the Maharaja for accounting purposes.

On the House of Nakai there is an interesting mention of how Sardar Atar Singh and Sardar Ishar Singh converted to Islam and yet retained their aristocratic lineage. Sardar Mohammad Arif Nakai and Sardar Mohammad Suleiman Nakai uphold the tradition of the family, among others, later on.

And how the House of Harika had its origin in Mathura, from where it shifted to Gurdaspur, then to Jaisalmer, is rivetting. A family member down the lineage moved to Patiala and became the Chief of General Staff of Patiala. There is the House of Jaijee which refused to pay jizya to the Mughal rulers and got the subtitle, Jaijees.

The history of the Maharaja’s court would be incomplete without the involvement of the ladies who were able administrators and even went into battle. Maharani Jind Kaur is a classic example where the Queen Mother was in complete charge of the state.

(H. Kishie Singh is a journalist, author, motoring aficionado, globe-trotter on wheels and a public speaker. He has authored two books: Good Motoring, and Whispering Deodars, co-authored by His Holiness The Dalai Lama, the late Khushwant Singh and Satish Gujral, Ruskin Bond, among others.)

@rukssaluja @bobbysinghbansal