Meghnad Desai’s new book, which takes even those uninitiated in economics through the puzzles and wonderment of the subject and its evolution, emphasises the importance of redistribution of wealth

BY DR SANJEEV CHOPRA

Never having been a formal student of economics, I approached this book with a degree of trepidation— but from the foreword itself it became clear that Desai’s purpose is not to show off his knowledge of economics but to engage with the general reader about the essentials of economic theory and the evolution of the subject from the time of Adam Smith to the present. He covers a long span— starting with Adam Smith’s Inquiry, and goes on to discuss the economy of redistribution as well as the imperative of focusing on lives and livelihoods especially in the postpandemic world, for the resource-poor suffered much more than those who were privileged to fall back on their savings, and more importantly, the network of institutional support. For Desai, the patron saint of economic theory, Adam Smith’s first book The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which ran into five editions, is actually the precursor to his famous book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (WN). The core argument of this treatise is that “the wealth of nations is not in its treasure of gold and silver, but in the productivity of its labour.” This value was to be measured “by the amount of the worker’s time contained in the product”. He argued in favour of free trade as he felt that it “would enhance productivity as well as revenue which would enhance the incomes of labouring people rather than the monarch’s coffers”.

However, after Smith wrote his magnum opus in 1776, the world and especially England was shaken by two cataclysmic events: the American War of Independence (1775-83) and the French Revolution (1789) which changed the style, content and context of political economy. When Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population, he also implied that unless workers were kept at subsistence level, their numbers would grow to unmanageable proportions and this helped the Ricardian notion of the “iron law of wages”. As Desai puts it, “Malthus provided the crucial link between wage levels and population levels among the labouring classes which fastened the lock on any prospect of improvement in the lives of the majority.”

In sharp contrast to Smith, who called his work Inquiry, Ricardo elevated the status of his writing to Principles—which implied that he was quite certain of his assertions. According to him, “the produce of the earth—all that is derived from its surface by the united application of labour, machinery and capital is divided among the three classes of the community; namely, the proprietor of land, the owner of the stock or capital necessary for its cultivation and the labourers by whose industry it is cultivated … the proportions of the produce will be allotted under the names of rent, profit and wages.” Ricardians regarded these principles to be the laws of nature, rather than of society. He also postulated a connection between paper currency and inflation, and linked paper to gold reserves.

In 1848 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto and challenged the Ricardian thesis about society and polity. According to them, “the mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life”. The second half of the 19th century witnessed both industrial and political revolutions in Europe and America. The demands for adult suffrage—at least for all able-bodied males—gathered steam, and set the stage for women seeking political equality as well. By 1911, the supremacy of the House of Commons over the House of Lords was established for all time to come.

By the early 20th century Alfred and Mary Marshall wrote The Economics of Industry and later The Principles of Economics which became the universal textbook for economics all over the globe. Marshallian economics brought economics back to the ordinary behaviour of people in their day to day transactions of buying, selling, saving and earning. This also led to the establishment of a global corps of economists who spoke the “same language” and used the same analytical tools to understand the puzzles and wonderment of economics. These new economic mandarins joined the civil services, finance departments, and later multilateral organisations.

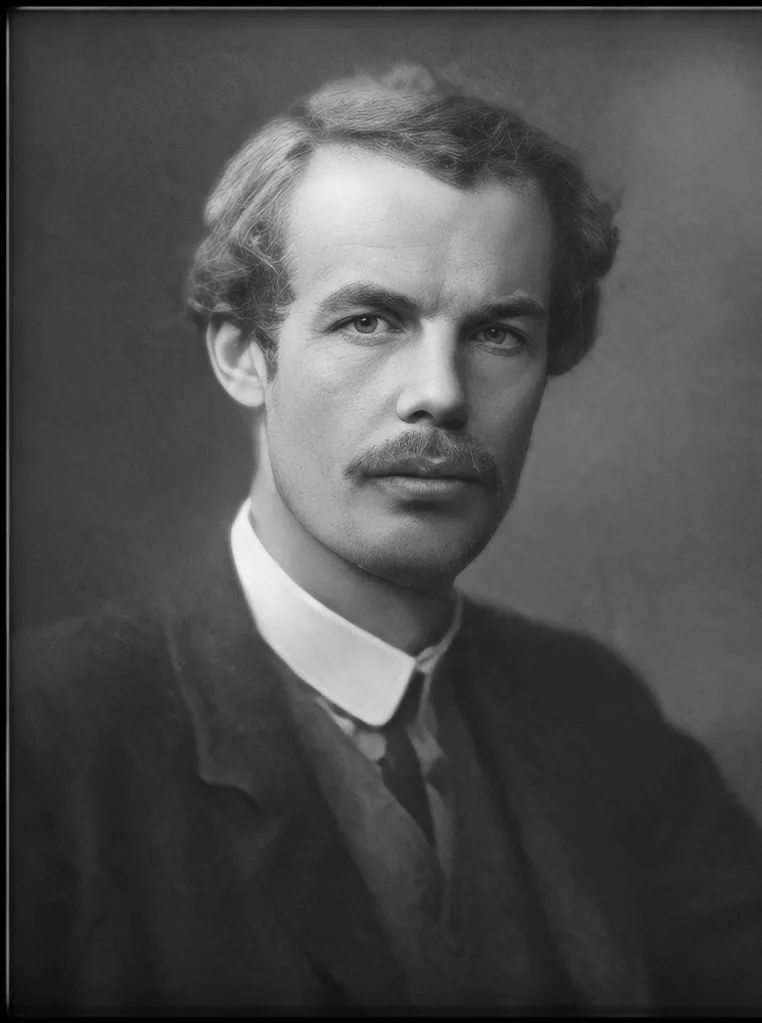

Marshall was succeeded in his Cambridge chair of economics by Arthur Cecil Pigou, who was just 31 at the time of his appointment. Pigou published Wealth and Welfare in which he argued that the principal concern in economics should be about the redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor. In fact, from the first UNDP report, the focus has been on the coefficient of distribution of personal incomes rather than the overall GDP of a nation. Desai is an unabashed acolyte of Pigou, and calls him the (first) green economist.

However, Pigou’s thunder was stolen by John Maynard Keynes, who launched his version of New Economics in 1936. Keynes pioneered the introduction of uncertainty and the role of expectations in macro economics. Although the idea of expectations had first been raised by Gunnar Myrdal in Money Equilibrium in 1933, the English version of this work was published only in 1939. Keynes argued that consumption was a better index than savings, and the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) was made a central part of the model.

But the consumption theory was challenged by Milton Friedman who wrote A Theory of Consumption Function, based on the statistical data of family budget surveys and the time series data for the aggregate economy. He showed that the Keynesian consumption function did not correspond with the family budget data, and postulated his own permanent income hypothesis, according to which the spending decision of families was based not just on current incomes but on a sort of average of past, current and expected incomes.

The next major milestone in global economics was the abandonment of the Gold Standard for good by President Nixon on August 15, 1971. Till this announcement, the US dollar was sticking to the Bretton Woods proclamation of Roosevelt by which the price of an ounce of gold was fixed at $35. Realisation dawned that the real value of a currency was actually a function of the national monetary authority! Two years later, the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) delivered a shock by quadrupling the price of oil from $3 to $12. This, coupled with space travel and satellite communication, led to the shift of manufacturing from Europe and the US to Asia: South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan and Singapore. Meanwhile, the Soviet system collapsed, and the World Bank began to frame anti-poverty programmes with a clear focus on redistribution. In 2008, Wall Street crashed and in 2020 the Covid pandemic hit the world, thereby impacting the ability of nation states and their constituent units to respond to the health and food security needs of their citizens.

The pandemic has taught all of us that lives and livelihoods have to be the central concerns of all political economy debates. Desai puts this across in absolutely readable, nay, enjoyable text which I strongly recommend to all those interested in understanding the “wheels within wheels” of governance and polity.

(The reviewer is a historian, public policy analyst, and Festival Director at the Valley of Words, Dehradun. Until recently, he was the Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie.)