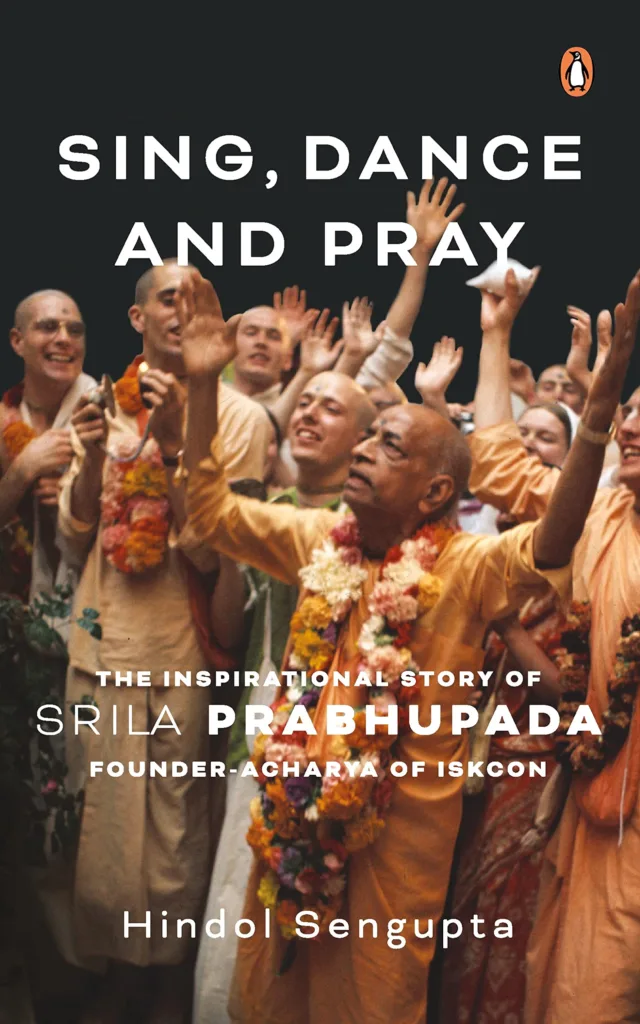

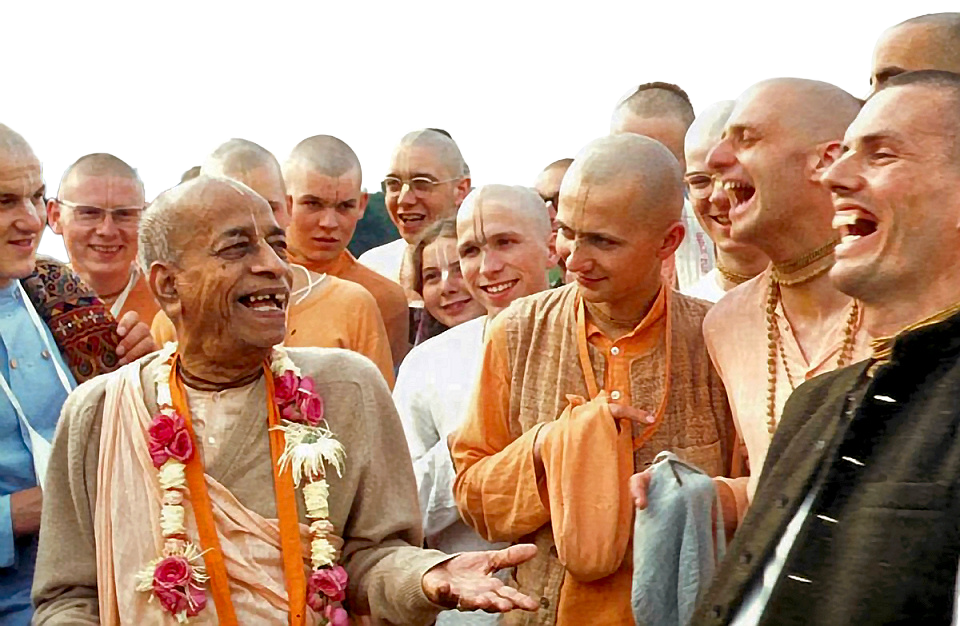

Historian Hindol Sengupta’s latest biography traces Srila Prabhupada’s journey from modest Calcutta environs to the shores of 1960s counterculture America where he amassed a following, founded ISKCON and continued his lifelong mission to spread the message of Chaitanya

By Dr Sanjeev Chopra

After two very successful biographies of distinguished Indians — Swami Vivekananda and Sardar Patel — who steered the course of history in the spiritual and temporal domains before and around the time of Independence, Hindol Sengupta now offers us the story of a cultural-devotional icon of the late 1960s, Srila Prabhupada. While Swami Vivekananda’s story The Modern Monk was set in the late 19th century, and Sardar Patel’s, The Man who Saved India, covered the first half of the 20th century, this can also be seen as a sequel to those definitive biographies. Mr Sengupta therefore deserves credit for offering us a wonderful way to understand the intellectual, political and cultural ferment of our nation.

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami aka Srila Prabhupada is so very different from the earlier icons. Vivekananda was the exponent of the Advaita, and Patel was the patron saint of the civil service; the muse for this book is the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in the US in the late 1960s. He was also an important cult figure in the Western counterculture of the Sixties marked by the protests against the Vietnam war and the senseless materialism and hedonism of American society. Spread over 18 chapters, the book traces the birth of Abhay Charan (AC) in a Suvarna Banik family of Calcutta in 1896, and his education at Mutty Lal Seal (the Anglicized version of Moti Lal Seal) School and Scottish Church College, where both Swami Vivekananda and Subhas Chandra Bose had studied before him. These were the years when AC studied not just Walter Scott and J.S. Mill, but also Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Kalidasa, the Vedas, the Bhagwad Gita and Vaishnav literature, as well as the editorials in the leading newspapers of his time in both English and Bangla.

The Vaishnava tradition AC was following had the distinction of ‘bookworm monks’, and Bhaktivinoda Thakur was a prolific writer who wrote Krishna Samhita (1880), Chaitanya Sikhshamitra (1893), and Tattva Viveka (1893) besides a monthly journal in Bengali, Sajjan Toshani. His writings caught the attention of Ralph Waldo Emerson in the US, Reinhold Rost in Germany and Sir Monier Monier-Williams, the Boden Professor of Sanskrit at Oxford, who reviewed his works in the journal of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Bhaktisidhanta Saraswati also became a publisher and got Vaishnava literature translated from Bengali into English, Odia, Hindi and Assamese. The publications in English were a classic case of the subaltern hitting back at the Empire — if missionaries were printing the Bible in Indian languages, the Hindus started publishing in English for the Western audience.

Two seminal events took place in Calcutta in 1920. The Congress held its session in the city and issued the call for non-cooperation under the leadership of Gandhi, and in Ultadanga locality Swami Bhaktisidhanta Saraswati renamed his ashram Gaudiya Math where he was soon to meet his most famous disciple, Abhay Charan. The young Abhay argued that while the land of Chaitanya was still under the colonial yoke, the first effort should be to free India from the British. However, for Bhaktisidhanta Saraswati, “the message of the divine could not wait for politics of mere mortals. Krishna’s lessons could not be held back by the political circumstances of India; indeed the world of the divine was not merely confined to people in India. It was for everyone.”

Although Abhay Charan was not successful in business ventures in Allahabad, Lucknow and Bombay, his association with Gaudiya Math and his public speaking skills in English soon gained recognition. By the mid-1930s, he had lost his business and his father as well as his spiritual mentor, but his association and work for the dissemination of the message of Chaitanya became central to his life and mission. He found an international publisher in Thacker, Spink and Co. and published Back to Godhead, and also announced the publication of his magnum opuses — a detailed exposition on the Bhagwad Gita as well as on the life of Chaitanya Maharishi.

Post-Independence, he started his work at Birla Mandir, New Delhi, and then at the Radha Damodar temple in Vrindavan, the birthplace of his beloved Krishna. It was here that he conceptualised the 60-volume commentary on Bhagavatam — all 18,000 verses. To give this number a context, it may be mentioned that the Bhagwad Gita has only 700 verses. Two notable people who ensured that some copies of the book were purchased for public libraries were Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Vice-President Dr Zakir Hussain.

Finally, in 1965, with free passage from the Scindia steamship company aboard the Jaladuta and a sponsorship from Gopal Aggarwal of Pennsylvania, he set sail for America and landed in New York, which was then “one of the filthiest cities in the world”. When he landed in November of that year, the city faced its worst blackouts, the counterculture of the hippie movement was in full force, the opposition to the Vietnam war, militarism and the war machinery was at its peak, and people were flocking to the East Village where along the sidewalks, hippies performed, recited poems, chanted or engaged in ‘be-ins’, ‘be-outs’ and ‘happenings’. In this audience, which included George Harrison, Yoko Ono (later partner of John Lennon), Harvey Cohen and Bill Epstein, entered AC Bhaktivedanta with his melodious voice, dance and prayer to create the first, and perhaps the only, ‘multiracial safe space’ in a city which was in the throes of endemic violence.

Sami Krishna, as he was famously called, also paid equal attention to food — for he felt that well-fed bhaktas sang and danced better! Soon Allen Ginsberg was a follower, and he helped him to extend his stay in the US. When the Sami reached San Francisco, he was almost like a rock star, and had built a cult following, many of whom were former junkies, but had agreed to abjure drugs and sex outside of marriage as part of the initiation rituals. Gradually, as his fame increased, he was invited to lecture at many universities, including Harvard. He also set up base in London, and temples everywhere around the globe, but his heart was in the Krishna temples at Nabadwip and Mathura, the places associated with Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and Lord Krishna. By the mid-1970s, he was in conversation with leaders from the world of industry (Gerald Ford) and of politics (PM Indira Gandhi and her successor, Morarji Desai). His movement was flourishing, books were selling, new devotees were being initiated and the impact was being felt. In the autumn of 1977, when he felt that his mortal life was ebbing away, he chose to spend his last days in the holy town of Rishikesh on the banks of the Ganga.

However, there are certain questions and controversies which Mr Sengupta should have addressed. The ISKCON movement has been under attack from both the Left and Right. The CPI(M) was never comfortable with the growing influence of ISKCON in Krishnanagar. While this is understandable, the Rajiv Dixit group is also very critical of ISKCON on the grounds that the organisation is not transparent about its governance and accounting systems. The internet is also replete with controversies surrounding the movement, and readers would have preferred it if Mr Sengupta had responded to these as well. Perhaps he could do so in the next edition.