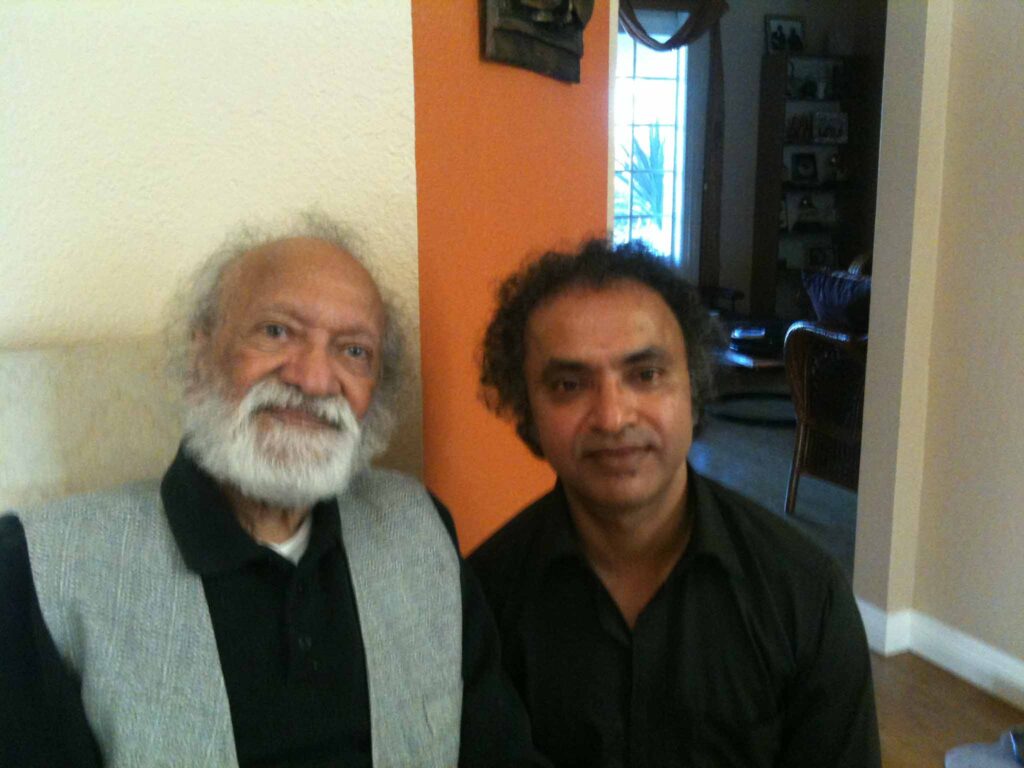

Author and art columnist SUJATA PRASAD in conversation with acclaimed composer and performer SHUBHENDRA RAO, Pandit Ravi Shankar’s foremost disciple. This year, April 7 marks the sitar maestro’s 102nd birth anniversary

Q: In a poignant obituary, written for The Guardian after the maestro’s [Pandit Ravi Shankar] death in December 2012, Amit Choudhury remarked, “an epoch has passed, not only in north Indian Classical music but for a certain buoyancy and colour in the music of the long 20th century”.

A: Artists like him never die. They live through their music.

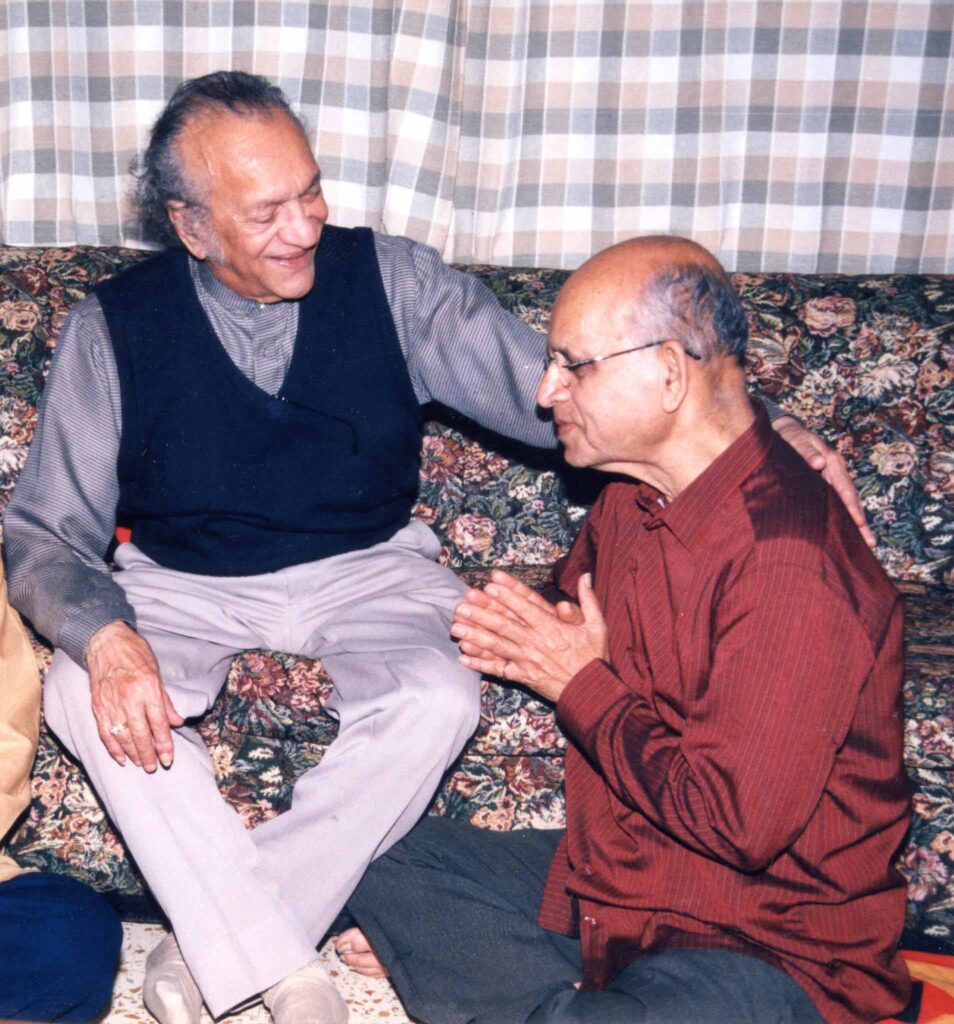

Q: You had a very special relationship with Pandit Ravi Shankar. He was not just your guru but your father’s guru as well.

A: Yes, my father, N.R. Rama Rao, was one of his earliest disciples. A young science graduate, just out of his teens, he reached out to Panditji after attending a concert at the historic Bangalore Town Hall. To say that he was mesmerised would be an understatement. He was completely entranced by the complex rhythms of the unfolding ragas, the improvisations, the intricate crescendo of the closing notes. He made his way to the green room. Fortunately, my father was not a complete greenhorn. His mother had lived in Pune for a long time and could understand the intricacies of Hindustani music. My father imbibed that from her.

Q: How old was Ravi Shankar at that time? Where was he based?

A: We are talking about 1948. Panditji was 28 years old and was working at All India Radio in Delhi as the director of the network’s instrumental ensemble. Encouraged by his mother, my father came to Delhi and took up a small job in the Congress office. He spent most of his time in Panditji’s tiny apartment at Hailey Road. He was present during his long practice sessions with Annapurna Devi and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, providing accompaniment on the tanpura. Their bonding as guru and shishya endures in endearing anecdotes about “Rambhakt Hanuman and Ravibhakt Rao”!

Q: Was he already a global celebrity?

A: He was certainly an Indian celebrity, recognised in the discerning music circles of Kolhapur, Pune, Belgaum, Aurangabad, Nasik, Baroda, and elsewhere. He was also a celebrated composer. The Satyajit Ray trilogy would come later, but his scores for Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s Dharti Ke Lal (1946) and Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946) were already making waves.

Q: You have spoken about the festive atmosphere that would set in weeks before his arrival in your hometown, Bangalore. A: Yes, it was Holi, Ganesh Chaturthi, and Diwali all rolled into one. A week before his arrival, our small home would be spruced up. He was our god. In our puja room, there were only three deities who were worshipped — Dattatreya, Adi Shankaracharya, and guru Ravi Shankar. My father’s guru bhakti was unmatched. My mother, an accomplished Carnatic vocalist, was as devoted to him as my father.

Q: Do you remember your first interaction with him?

A: Yes, vividly. My first memory of him is from 1968 when I was not even four years old but had begun running my fingers on my father’s sitar. Guruji came to our home to meet my grandmother, accompanied

by Ustad Alla Rakha, and his son, Shubhendra, after whom I was named. There was a buzz surrounding this visit. His US and Europe music tours, topped by his incredible performance at the Monterey International Pop Festival in California in 1967, had turned him into a global music icon. He was christened ‘the godfather of world music’ by George Harrison. I remember playing a small composition in Raga Yaman for him. Impressed with my talent, he taught me the right posture of holding the sitar, since I was keeping it on the floor like a Saraswati veena. My first formal lesson came rather unexpectedly in 1973 in Mysore. Right after a concert, he taught me the chalans of Raga Bhairav and a small composition. From then on, once a year, sometimes twice a year, I would get his attention. He was by now an unassailable superstar, his gift for melody was being likened to that of Mozart and Beethoven, and he was collaborating with maestros like Yehudi Menuhin, John Coltrane, Jean-Pierre Louis Rampal, and iconic composer Phillip Glass.

Q: When did the regular classes start?

A: I continued my taalim under him by visiting him in different places in India, whenever he had time for me. I remember being given lessons in Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad, and Chennai. I managed to get his undivided attention in 1982 when he was stationed in Bombay for two weeks to work on the soundtrack of Richard Attenborough’s film on Gandhi. Every morning, despite his tight schedule, he would mentor me for three hours. We would have lunch — his favourite homemade fish curry, rice, dal, vegetables, and a small Bengali sweet — before rushing to the studio.

Q: Any special anecdotes that you would like to share?

A: Oh,yes. It was 1983, just before a concert with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan at the Shanmukhananda Auditorium in Bombay. It was a red letter day in the city’s concert calendar. The hall, with a seating capacity of more than 2,500, was packed, with dozens of people sitting or standing in the aisle. While driving to the venue, we noticed a huge anti-drug hoarding. Guruji pointed to it and made me promise not to ever succumb to the temptation to take drugs. “Make music your opiate for all times,” he said. That was also the year when I first played with him in a sitar ensemble at a festival at the Siri Fort in Delhi, in memory of Uday Shankar.

Q: You moved to Delhi in 1984 to study music in an unfettered way…

A: Yes, his place at 95 Lodhi Estate became my gurukul for nine years. The other resident disciple when I moved in was my gurubhai, the renowned sarod player, Parthasarathy Choudhury. Guruji would spend 80-90 days in Delhi each year. The two of us ran the house and submitted ourselves to the rigour of hours of riyaaz. Guruji remained present even in his absence. In true guru-shishya parampara, we surrendered ourselves to him. For him, music was a spiritual quest, a way of life. It became our quest too. He nurtured our innate talent and gave us deep insight into what it entails to become a complete artiste, as only he could.

Q: You have often said that the date that remains etched in your memory, that you cherish most, is the day you shared the stage with your guru in the Convention Hall of Ashok Hotel. A: Yes, it was so unexpected. He was supposed to play with Pandit Uma Shankar Mishra, who, for some reason, had dropped out. Guruji asked me to tune the sitar at noon. I failed to comprehend what was in store. It was much later that it dawned upon me that I was the chosen one. I was ecstatic, in seventh heaven. After the concert, he said that it was a good start and that I had played well. After that, I frequently toured and performed with him, and assisted him in his orchestral compositions.

Q: Any other special reminiscences?

A: His extraordinary warmth and generosity. He loved Saskia [renowned Dutch cellist, composer, and educationist Saskia Rao-de Haas] and her music. He could not attend our wedding in Bangalore. He and his wife, Sukanya, whom we fondly call Chinnamma, surprised us by organising a party for us later. Another special memory is of his visit to the hospital a day after Ishaan, our son, was born. He held Ishaan in his arms and blessed him. And I vividly remember our last meeting in 2011. I had just finished a three-month US concert tour with Saskia and was leaving for Mexico. Guruji was not well. I was with him for two hours in a hospital near his home in California when he said, “Beta, I feel bad I could not give you the time you needed. I was busy with my own concerts at that point. I am really glad that you are doing well. I am confident that you will carry forward my legacy. My blessings are with you.”

Q: In a video that is now viral, he is seen performing at the Terrace Theatre in Long Beach, California, a few weeks before his death. He is seen arriving in a wheelchair, wearing a nasal cannula. He looks extremely frail, but that does not stop him from playing a raga, Pancham se Gara, a raga created by him. He is aided by his daughter, Anoushka. He seems to know that this will be his last live performance. A: Yes, it was an evening resonant with raw emotions. At the end of the performance, there were tears streaming from our eyes. It was an event few will forget. He has gone but his music will endure … his incredible, unforgettable music.