Indian films have always focused on women but, as microcosms of societal norms, usually furthered popular perceptions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ women with annotated notions of ideal conduct or waywardness

By Dr Pallavi Jha

The role of women within Indian society has been a topic of Indian cinema from its very inception. A bunch of films has discussed problems relating to women. The cinematic portrayal of women reflects their social role as mothers, wives, daughters. Women are often seen as objects, and they are devalued in the process. However, throughout the evolution of Indian cinema, there have been attempts to change this limited view of women and give them a more meaningful position in films.

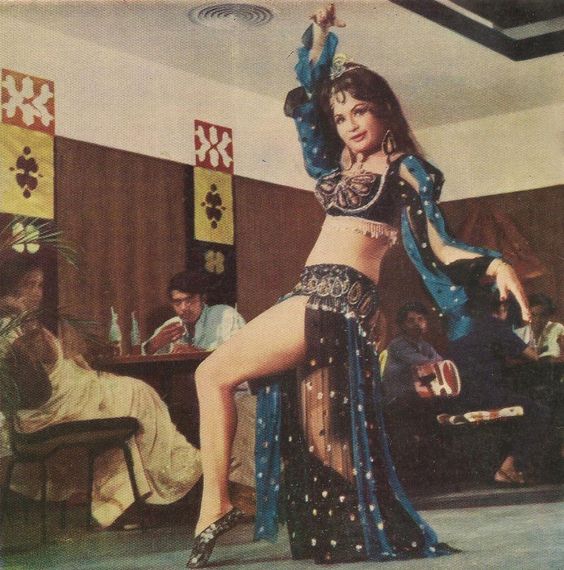

Cinema in India suffers from the Sita and the Menaka complex (also known as the Madonna and Whore complex). Drawing from mythology, Sita (Madonna) is the perfect mother, wife, daughter, and sister. Menaka is the outsider who does not comply with social norms and is rejected at multiple levels. These are the vamps. The vamps are basically Eastern interpretations and imitations of Western women. They are the complete opposite of what traditional Indian women should be, and they are always depicted as objectionable, specifically in a sexual connotation. They are often seen dancing, drinking, smoking, and being immoral. Often, the audience does not empathise with the vamp, and she is typically punished in the film for her obnoxious actions. Patriarchy has a strong hold over society and thus over cinema as well.

There are social constructs about women in India. Some women are seen as replicating Sita, and then some as Menaka. Sita: the docile, obedient wife, the caring mother, the ever-sacrificing woman for whom self-respect is cheaper than her husband’s decisions. These are the mothers, sisters, and wives in mainstream Hindi cinema. Their identity is that of either their fathers or husbands. And then we have Menaka, the whore. Another popular portrayal of women in Indian movies is the character of the vamp, which is precisely the opposite of the ideal wife or mother. The vamps were characterised as women who showed disrespect for traditional values by emulating Western women. Furthermore, they were shown drinking, smoking, partying, visiting nightclubs, and being promiscuous. Thus, they portrayed the characteristic traits of an immoral person, with unacceptable and offensive behaviour that was punishable. They live life on their terms and do not abide by social norms and orders. These are women who are generally unaccepted by society as a whole. And films have been promoting this ever since.

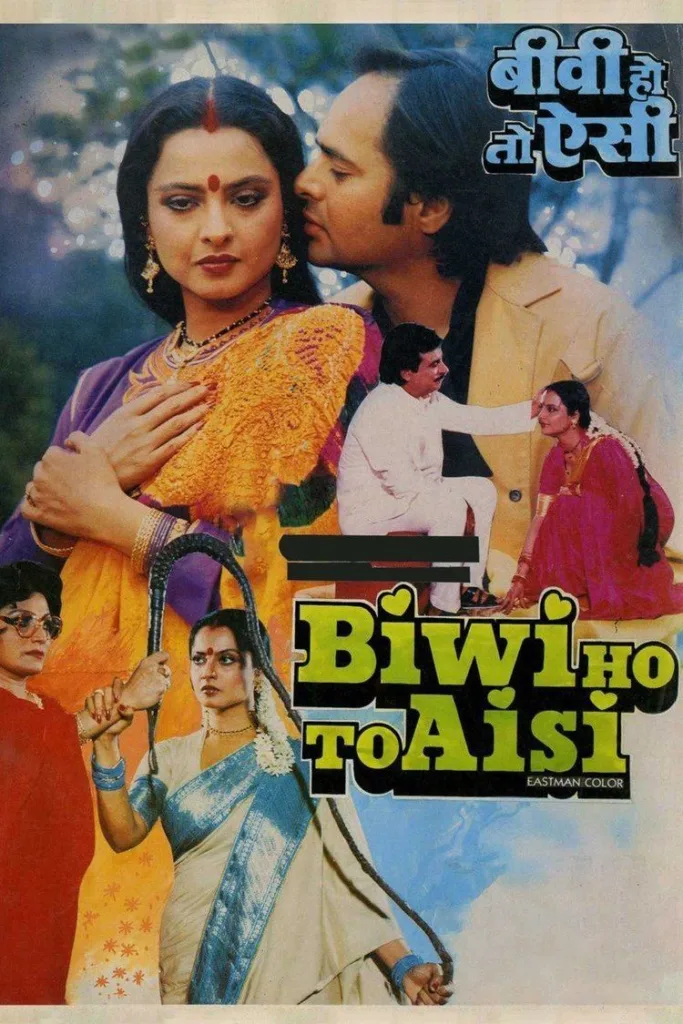

To understand this better, let us take an example. Let us analyse a film that has depicted both kinds of women. The film is Biwi Ho To Aisi (BHA) which was released in 1988. It is the story of the Bhandari family, a wealthy, privileged family led by an oppressive matriarch, Kamla (Bindu), the matron of the Bhandari family. She is the one who runs the business as well as the house. Kamla takes every single decision in both set-ups. She is ruthless and loud. To set the backdrop, the very first scene of BHA shows Kamla ruthlessly beating one of her domestic helps with a hunter for unintentionally breaking something she liked. His apologies and cries fall on deaf ears. The camera pans to a stuffed tiger on her exit, metaphorically comparing her to the tiger in the jungle. Kamla’s husband, Kailash, is introduced with an old song playing in the background, denoting his non-relevant existence.

Kailash (Kader Khan) is a timid, submissive, and meek man who has lost all his self-respect as well as respect in everybody else’s eyes for being an at-home spouse. Kamla needs her oldest child, Sooraj (Farooq Shaikh), to marry a girl whose economic well-being matches theirs. Nonetheless, Sooraj follows his heart and weds the not all that rich yet skilled Shalu (Rekha), who chafes Kamla continually. Along with her clever, conspiring secretary (Asrani), Kamla decides to throw Shalu with their wise and shrewd strategies against her.

However, despite the evil moves, Shalu tries to be a devoted daughter-in-law by attempting to win the heart of Kamla. She has the complete support of her timid but righteous father-in-law. Vikram, a.k.a. Vicky (Salman Khan), is Kamla’s perfect son who, just like his mother, believes in money and show-off. But, with Shalu’s continuous attempts, Vikram becomes a new person who cannot bear the barbarities dispensed to his sister-in-law and gets vocal in fights against his overbearing mother.

After unlimited endeavours at bearing mortification and individual assaults, Shalu hits back in her style, and her actual personality is uncovered towards the end. She stuns everybody, including the audience, with her expressive English, which contrasts with her ‘illiterate woman’ image. Her father, Ashok Mehra (Om Shiv Puri), a family companion of the Bhandaris) uncovers her actual personality. Kamla discovers that Shalu is the Oxford-returned girl, who, in conspiracy with Kailash, got married into the family to mend “Kamla’s ways” and beliefs. Kailash, for the first time, gets unexpectedly vocal against Kamla. Kamla understands her blunder and apologises for her conduct. Kamla genuinely apologises for everything, and joy and happiness enter the Bhandari family unit.

Shalu is presented as fearless as she fights with the local goon. She is not a damsel who needs to be rescued. BHA has tried to change many gender roles, but most of these have not been for any good. For example, Arti (Renu Arya), who loves Vicky, intervenes in his personal space at any given moment. Vicky disapproves of her advances, but Arti does not respect his decision. This, in the film, has been depicted as Vicky’s feudal mentality towards people from the less privileged section. But Arti, time and again, is shown disregarding the sense of privacy. The film also exhibits a lack of social choice of marriage for children in society. The film cracks sexist jokes rampantly; the only difference being that the men are the pieces of mockery.

With Shalu entering the house, BHA becomes a movie where one woman is pitted against another. The one who defies the social order (read Kamla) of how a woman should behave is demoralised. Shalu is perfect as she takes care of the kitchen, sings bhajans, and owns all the house responsibilities. The film also looks down upon short clothes, fast music, and partying, bringing these all under one umbrella of Westernisation.

In its desperate attempt to reverse the gender roles, the film also brings out the typical masala film villain in Kamla and hero in Shalu. Kamla makes many efforts at killing and trapping Shalu, but all are in vain. Adding to this terrible story, in a scene in BHA, the father says that a woman thrown out of her in-laws’ house has only two options: one is to go to her parents (which apparently is a shame for a girl’s parents), and the other is to commit suicide. BHA blatantly shows hitting, including physically torturing the domestic staff and the family members. For instance, Sooraj slaps Shalu for disgracing the family’s name by consuming alcohol.

BHA has been the cliché victim of the Sita and Menaka syndrome. Kamla is a busy businesswoman who also has a life of her own. She invests time in herself, the way she looks, and her regular kitty parties. The film does make it a point to show that Kamla also takes care of domestic chores. She runs her family’s business successfully. But since a woman has to be under societal control, it becomes important for films like BHA to depict a woman in a certain way from the very beginning. Despite all her strengths, Kamla is loud, authoritarian, and ruthless. A woman with such power is difficult to put a social leash on and is thus represented in a negative light. Her negativity is shown to the extent that in one of the scenes, she is shown hitting a male domestic help with a whip for breaking a vase. With the progression of the movie, Shalu enters as a rustic, rural woman. Shalu is independent, physically and mentally strong, and takes her decisions herself. But the film sadly pits one woman against the other. On the one hand, Kamla hates Shalu for being uneducated, poor, and unpolished. But, on the other hand, Shalu is traditional, takes care of the family, sings bhajans in the morning, cleans everyone’s rooms, and does all the kitchen and house chores herself. Kamla is financially independent and can afford to pay for domestic helps. But, as instructed by society, a woman must take care of her family herself, and Shalu epitomises the idea.

But looking keenly at Kamla’s character in BHA, it is understood that she is a victim of oppression and thus a carrier herself. In a scene where Sooraj is annoyed with his mother’s control over his life, Kailash tells him how he got trapped in the marriage. Narrating the story, he says that being an honest worker in the company, the owner married off his indisciplined daughter, Kamla, to him. From here, it can be noted that Kamla, depicted as class-conscious, was married to someone below her class, which she must have disapproved of. Also, to be taught the lessons of a ‘good’ Indian woman, she was married off. For a ‘good’ Indian woman, marriage comes with many responsibilities. The underpinning of the scene from a gender lens could be that Kamla was not given a choice of who she wanted to spend her life with and was married to an unknown man her father thought was right for her. Thus, Kamla comes out as a victim, a socially oppressed woman whose insecurities make her bitter. Having said that, it is also essential to highlight the end of the film. In the climax scene, Shalu reveals herself to be an Oxford graduate and the daughter of a wealthy industrialist. She was part of a real-life play directed by Kailash to bring Kamla onto the correct path of being a traditional wife, good mother, and good house-maker. Society and so cinema have preconceived notions about gender. The gender roles are fixed and must not be altered. BHA finally abides by this law, and the control of the family goes to the men.

BHA is a film that promotes deep-rooted patriarchy, but the carrier is a woman. The moral frames for the daughter-in-law are kept tight; a woman who performs specific duties only could be a good wife. If a woman does not act according to societal rules, her upbringing is to be condemned. The film very conveniently also engages in the age-old belief that an illiterate woman is an uncivilised woman. As the name suggests, BHA is an encyclopaedia of how a perfect wife should be. It draws the line firmer and makes it more stringent for women to behave in certain ways pertaining to the regulations set for them. And those who do not, are misled and need to be brought into the fixed bracket. BHA has no doubt experimented with replacing patriarchy with matriarchy, ending up strengthening the oppression of women.