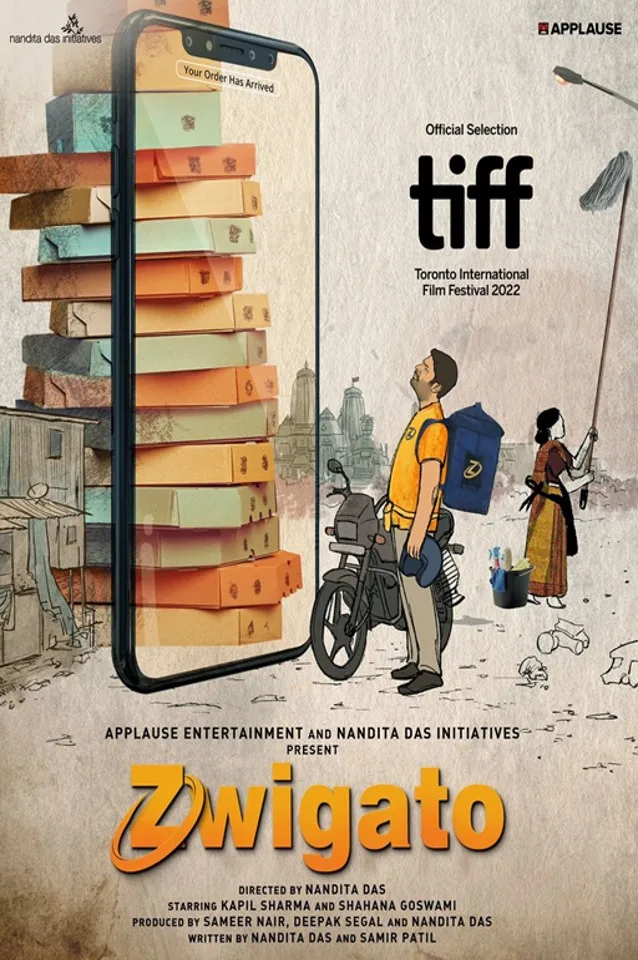

In Zwigato, Nandita Das takes a memorably empathetic look at the simple yet inordinately difficult to fulfil aspirations of small town India through a heart-wrenching tale of a migrant delivery executive

By Shinjini Kumar

In the iconic movie An Affair to Remember, Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr go through a series of heartbreaking twists and turns before they unite. If this story were to be based in 2023, Kerr would have been talking to Grant on the phone while she met with the accident and he would have come right away to help. Sorry to be a killjoy, but when I watch films or read fiction, I get carried away by the role technology plays in our lives, work, relationships, even love. In some ways, we are like cyborgs already, with powers and superpowers for humans, but also deep divisions and complexities because not all humans do, or can, access and use technology in the same way. Our stories then, are as much a reflection of our emotions and societal values and norms, as of our age of technology.

If that were not the case, someone like me, a fintech founder, would not be writing about Zwigato, a film by Nandita Das, which premiered recently. More often than not, when cinema deals with technology, it is in rather obvious and scary ways, bringing us the future of galaxies, AI, or viruses; an artistic expression of our collective fear. More rarely, cinema puts the human condition at its core and yet makes us aware, in more nuanced and poignant ways, about how changes in technology touch our humanity, sometimes elevating and sometimes debasing us. Zwigato tells a simple story, with elegance and power, that makes us aware of the disenfranchisement of many participants in the dream of new India and our own desensitisation and lack of empathy towards the aspiring masses and their vulnerable lives.

The sinking feeling in your heart comes from the predicament of the protagonists, Manas Mahto, with his forever expanding and contracting ego, that he feels entitled to as a man, but can hardly afford, and Pratima, with her tiny ambition to preserve not just the economic well-being of the family unit, but the love and happiness that seems to be slipping out. You want to laugh and cry with the protagonists, but you also want to dream with them and make their dreams come true. Where the film scores over other films dealing with economic vulnerability and the capitalist system is in this constant build-up of emotion, where you expect the next scene to make things worse, or, equally dramatically, make them happy ever after. Neither happens. It starts to feel like life and you get involved with the lives of millions of people with simple, wholesome aspirations of food, shelter and education for their children which seem so tantalisingly within reach, but also slipping away, like Manas’ rating on Zwigato. It is not an easy feat to achieve, but Das does this with her little unsparing tricks, pulling you in and twisting your conscience to ask yourself — why is it so hard?

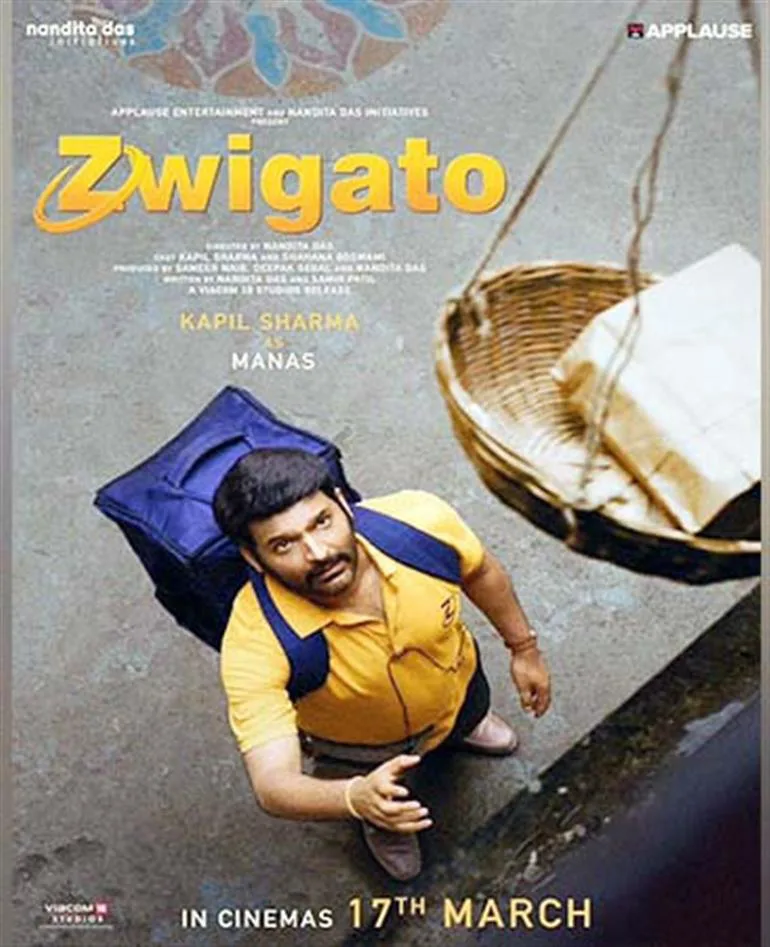

The main trick is the casting itself. Kapil Sharma is the happy man of India. His comedy is obvious, crass, sexist, politically incorrect and extremely popular. He is the rags to riches, mental health hell-and-back man who is the poster child of post-liberalisation India. From small town Punjab to ruling the world of comedy, he has done it all. He is perfect for the role of Manas, the Hindi-speaking migrant delivery boy from Jharkhand. He is an insider-outsider, sitting on so many fences; in his political views, language, work (he is not a regular delivery boy, he becomes one because he loses his job as a manager in a factory), personality (he is the patriarch whose ego is bruised when his wife tries to find work, but he also helps with housework and children). He does not stand out from the crowd of delivery men with his little paunch and fuel-guzzling two-wheeler, chasing ratings and incentives, but he also stands out in his fight for self-respect against the mechanical ‘system’. His struggle and dream for a government job is the dream of millions in his position, but his dreams are also of racing against a high-speed train and Bollywood-style romance with the glamorous avatar of his simple, beautiful wife.

Shahana Goswami is the foundation of the household and delivers a powerful performance, looking every bit the migrant woman with deep, secure roots in her culture and community. She is a new icon in a way. Pratima, with grown children and a mother’s body, trying out the uniform of the Mall janitor and feeling like she can take on the world — “I may look like an ant, but I have the power of an elephant” — is in the rather short line-up of women characters in Indian cinema who leave a mark in the evolution of what it means to be a woman in this society. It is easy to fall in love with her and own her aspiration to not just save her family from financial ruin, but also to become something more than she is — the stretch and flex of the ant to be the elephant.

The other coup is the location. What’s not to love about Bhubaneswar — beautifully shaded avenues, nice homes, gorgeous sculptures and temples casually dotting the skyline, new cafes and restaurants jostling with traditional eateries serving delicious local meals.

For me, the film stood out for many things, but primarily many sensitive touches relating to class, caste, gender interactions and the insensitivity of newly affluent middle class Indians to migrants, the working class and their struggles. It is a mirror to new India, with all its inequalities and indignities. This is the kind of cinema that must be watched by all, especially young people who have growing discomfort about their world, but cannot pinpoint their restlessness and discomfort or find an outlet for it.

The beginning and the end of the film stayed with me for being gorgeously shot and positive in the midst of the almost nihilistic story. It is very hard to think of the end of a film like this. But this is where Zwigato scores. The one thing that could be better was the length of the first half of the film. The pace sometimes falls short, like the fuel in Manas’ bike. But hold on and be ready to be rewarded. Once the story moves, it carries you along, twisting your heart into knots. For someone like me, the film also raised many questions about the crossroads where technology has brought us and if we can set a better mission statement for ourselves and our future.