Pride surges in the hearts of all Indians living in the country as well as abroad when they look at Tiranga, our tricoloured national flag, being hoisted, and fluttering high above. Eminent vexillologist Sekhar Chakrabarti shares with Namaste Bharat how the national flag as we know it today came about, and how and when it is displayed…

By N. Kalyani

The national flag evokes a spirit of freedom, nationalism, oneness, unity, integrity, and a common purpose. The fluttering Tricolour flying high stirs up patriotic sentiments in the heart of every Indian including the diaspora spread across the globe. What were the beginnings of the development of the national flag?

“The question of a national flag for India began in the late 19th century, when the leaders steering the freedom movement in India became passionately infused with the spirit of reasserting the country’s freedom. The first serious attempt at indigenous flag-making came from Sister Nivedita. She conceived the idea of the national flag during a visit to Bodh Gaya in 1904.” Sister Nivedita, born Margaret Elizabeth Nobel in Northern Ireland, was a devotee of the great Indian spiritual luminary, Swami Vivekananda, who named her thus, Nivedita meaning ‘the dedicated one’. She moved to India and became actively involved in the India’s freedom struggle. An article by Sister Nivedita was also published in the Modern Review of November 1909 in which she wrote on the subject with great fervour.

“Nivedita’s Vajra flag was publicly displayed in the Calcutta Congress Exhibition in December 1906. Over the years, other versions came and went.” Chakrabarti goes on to say. And what were these versions? “The Calcutta Flag was the first tricoloured flag hoisted on 7 August 1906 on the first anniversary of the Partition of Bengal. The Swadeshi flag was variously termed as ‘Boycott flag’ or ‘Bande Mataram’ flag. It was jointly designed by Sukumar Mitra and Sachindra Prasad Basu. The prototype flag was sewn by Kumudini Basu, sister of Sukumar Mitra. The flag was later hoisted by Dadabhai Naoroji in the Calcutta Congress in December 1906,” he narrates.

Chakrabarti goes on to mention the role of Madam Cama. “A strikingly similar flag was hoisted on 22nd August 1907 at the Second International Socialist Congress at Stuttgart, Germany by Madame Bhikaiji Rustom Cama. Waving the flag Madame Cama declared, “This flag is of Indian Independence…….I appeal to lovers of freedom all over the world to cooperate with this flag in freeing one-fifth of the human race.”” About the flag he says, “Dr. Bhupendranath Dutta (younger brother of Swami Vivekananda) in his book, Bharater Dwitiya Swadhinata Sangram (the manuscripts of the book were penned in 1922 in Germany) opined that it was Hem Chandra Kanungo (Das), a member of the Anushilan Samiti (a secret society), who was familiar with the Calcutta flag, who made the flag for Cama in Paris.” And continuing on the role of Madam Cama, he says, “On 19 December 1908, Madame Cama attended one of a series of lectures on ‘Indian Nationalism’ delivered by Bipin Chandra Pal in London. At the end of his speech Madame Cama demanded a hearing waving the tricolor flag.”

Chakrabarti takes us further through history. “Then came the Home Rule Movement in 1917. Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the two pivots of the Home Rule Movement, devised a new flag in consultation with Mohammed Ali Jinnah and B. P. Wadia.”

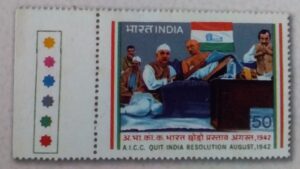

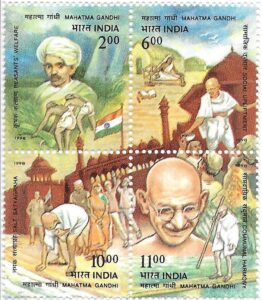

Subsequently, it was Pingali Venkayya (1876–1963), hailing from Masulipatnam, who founded the Indian National Flag Mission in 1916, and relentlessly pursued his goal to give shape to a distinctive pan-Indian flag. “In April 1921, prior to the Bezwada Congress, Mahatma Gandhi asked Venkayya to prepare a design. The charkha was placed on the flag as suggested by Lala Hansraj Sondhi of Jalandhar. The Swaraj flag was sufficiently popular to be hoisted on all Congress events. However, failure of the Swaraj flag to gain pan-India acceptance forced Congress to adopt a new flag.”

The Swaraj flag was subsequently amended, and in 1931 a new tricolor, the Purna Swaraj flag was born. “the new arrangement was in conformity with the basic principle of flag designing…..Saffron over white over green with a charkha (spinning wheel) in navy blue at the centre of the white stripe…..The saffron would represent courage and sacrifice, white would stand for peace and truth, and green would symbolize faith and chivalry while the spinning wheel would be an emblem of hope of the masses,” explains Chakrabarti.

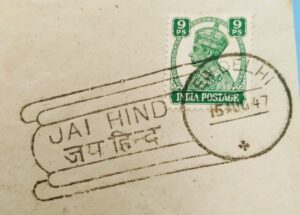

Independent India’s national flag came about from the Purna Swaraj flag – the charkha emblem replaced by Asoka’s Dharma Chakra (Wheel of Law) at the centre of the white stripe. Says Chakrabarti, “The Constituent Assembly on 23 June 1947 set up a nine-member flag committee that decided the Purna Swaraj flag as the national flag with a token alternation in its design by substituting Gandhi’s Charkha with Asoka’s Dharma Chakra. Approval of the ‘Chakra flag’ was accorded on 17th July 1947.” The wheel depicted in the flag has 24 spokes.

For Chakrabarti the study of flags is not confined to collecting real flags, but includes going through a variety of material such as books, government gazettes, archival documents,

newspaper clippings, advertisements, and collecting conventional and unconventional items like postage stamps, medals, coins and currency notes, match box labels, propaganda/publicity leaflets, objects associated with flag events and flag imprints.

Chakrabarti has represented India as the sole delegate in three consecutive International Congresses of Vexillology (ICV) – the 25th ICV at Rotterdam in 2013, the 26th ICV at Sydney in 2015 and the 27th ICV in London in 2017.

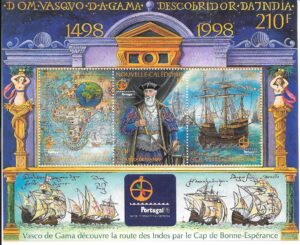

It is interesting when Chakrabarti goes back in time to trace the earliest reference to the term flag in India. He points out that the earliest reference to the flag, ‘ketu’, in India is in the Hindu sacred scripture, the Rig Veda, dating back to around 5000BC. And coming a long way forward to the 15th century it is the European flags that reached India with maritime trade activity such as the Portuguese, Dutch, English, French and Danish flags, and these are shown in the stamps that these countries brought out in the 20th century.

The earliest reference to the flag, ‘ketu’, in India is in the Hindu sacred scripture, the Rig Veda, dating back to around 5000BC

One also learns of the flags of the early Indian rulers such as Shivaji Bhosle, the great Maratha king of the 17th century; Tipu Sultan of Mysore in the 18th century, also known as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’, who adopted the tiger and the sun as his emblems, the sun, according to Sufi tradition representing “the source of divine light”; Maharaja Ranjit Singh under the Sikh golden yellow banner; the rulers of Chittor, the Ranas, who claimed descent from the Surya Vansi or Sun dynasty; and Rani Lakshmi Bai, who flew her Hanuman jhanda (flag).

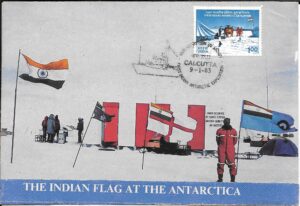

Coming back to the present. We see the national flag fluttering and flying high on many different occasions. On the uses of flags Chakrabarti says, “Flags serve many functions – coercing, rewarding, ordering, teaching, reassuring, and such other functions. Saluting a flag indicates acknowledgement of loyalty or submission. Flags are waved in celebration of national events. It is used to cheer our favourite team in sports meets. The flag is lowered at half-mast to indicate the death of a national leader or a dignitary. At the time of mourning flags are draped over the coffins of national heroes.” He goes on to say, “Flag events are interpretive symbolism. Freedom is heralded by the hoisting of national flag. Planting the flag mounted on an ice axe atop the conquered peak is a typical mountaineering tradition across the world.” Chakrabarti enumerates significant events that had the Indian flag related to them in some way. As for example the conquest of Mount Everest in 1953; the first Indian Antarctic Expedition in 1982; in outer space-on the moon as part of the Apollo 15 mission in the American Apollo space program in 1971; and as a medallion adorning the space suit worn by Squadron Leader Rakesh Sharma during the Indo- Soviet joint space flight in 1984.

Coming back to the present. We see the national flag fluttering and flying high on many different occasions. On the uses of flags Chakrabarti says, “Flags serve many functions – coercing, rewarding, ordering, teaching, reassuring, and such other functions. Saluting a flag indicates acknowledgement of loyalty or submission. Flags are waved in celebration of national events. It is used to cheer our favourite team in sports meets. The flag is lowered at half-mast to indicate the death of a national leader or a dignitary. At the time of mourning flags are draped over the coffins of national heroes.” He goes on to say, “Flag events are interpretive symbolism. Freedom is heralded by the hoisting of national flag. Planting the flag mounted on an ice axe atop the conquered peak is a typical mountaineering tradition across the world.” Chakrabarti enumerates significant events that had the Indian flag related to them in some way. As for example the conquest of Mount Everest in 1953; the first Indian Antarctic Expedition in 1982; in outer space-on the moon as part of the Apollo 15 mission in the American Apollo space program in 1971; and as a medallion adorning the space suit worn by Squadron Leader Rakesh Sharma during the Indo- Soviet joint space flight in 1984.

Flags are also displayed at various international forums such as conferences; state visits of heads of states and other dignitaries; in bilateral cooperation between countries; in diplomatic relations; in promoting cultural ties internationally; in international sports events like the Olympic Games; and in philatelic exhibitions.

For instance, of the Olympic Games, Chakrabarti points out, “At the opening and closing ceremonies of the Games, there is a parade of athletes: each contingent, dressed in its official uniform, must be preceded by a shield bearing the name of the country, accompanied by its national flag. It is a huge honour for any athlete who is selected to be the ‘flagbearer’ of his or her country.” And when it comes to the Indian contingent and the Indian Tricolour one has witnessed the fervour and verve shared by all of us.

On the use of flags Chakrabarti adds, “There are separate flag etiquettes and uses for military services. At sea we have separate flags for national identity and functions, and there is a set of international signal flags for marine vocabulary. And there are legal aspects, etiquettes, and protocols related to the use of the flag.”