The conflicting viewpoints and the inherent contradictions reflected in the fierce debate are well-documented

By Dr Sanjeev Chopra

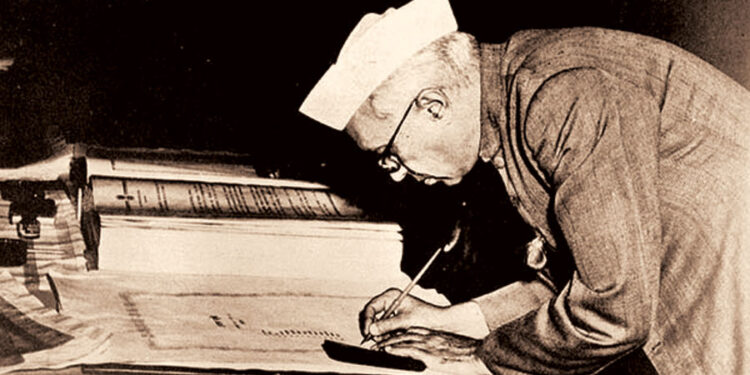

Tripudarman Singh’s Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India is a stellar work for it draws our attention to the circumstances leading to momentous changes in the governance and legal architecture of the country within the first few months after the inauguration of the Indian Republic. The seminal provisions of the Constitution of India which had been deliberated upon at length in the Constituent Assembly with a clear emphasis on fundamental rights, especially the freedom of the press, and on individual liberty were now coming in the way of implementing the social and economic reform agenda of the Congress party.

Tripudarman Singh’s Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India is a stellar work for it draws our attention to the circumstances leading to momentous changes in the governance and legal architecture of the country within the first few months after the inauguration of the Indian Republic. The seminal provisions of the Constitution of India which had been deliberated upon at length in the Constituent Assembly with a clear emphasis on fundamental rights, especially the freedom of the press, and on individual liberty were now coming in the way of implementing the social and economic reform agenda of the Congress party.

The Constitution of India, like constitutions across the world, had to incorporate multiple viewpoints – many of which were not in sync with one another. Thus, while the Mahatma wanted a minimalist state in which the gram panchayats would become self-governing republics, and only those functions which could not be performed at district and sub-district levels would be taken up by the state and Union governments, Nehru was all for a strong, centralised state which would “dominate the commanding heights of the economy”. While he was not quite comfortable with a strong and independent civil service, Patel was clear that without a strong All-India Service, providing the backbone of administration, the newly independent country would find it difficult to hold itself together. Thus came in Article 311. Dr Ambedkar was of the view that the ‘idealised village republics’ would never provide a platform for equity and social justice, and he too was in favour of strong state governments to implement the agenda of social justice. Many of these issues were resolved by making them part of the Directive Principles of State Policy – which were lodestars to provide a long-term vision, but not enforceable in the immediate or short run.

Singh places on record that what Nehru wanted to implement had long been part of the Congress agenda. Land reforms, zamindari abolition, nationali-sation of the core sector of industry and reservation for backward classes in education and employment had been part of the resolutions at the annual meetings of the Congress party from the 1930s. However, all these flagship initiatives had ground to a halt because the Fundamental Rights guaranteed in Part III of the Constitution gave the zamindars, the industrial magnates (who also controlled the press) and the educated elite the ability to challenge legislation. From the RSS-backed Organiser to the left-leaning Crossroads, the government of the day was subjected to intense criticism. It took recourse to the relevant sections of the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act (in the case of Crossroads) and the East Punjab Public Safety Act (in the case of Organiser), but both were declared void by the Supreme Court on account of their violation of the Right to Freedom of Speech.

Singh places on record that what Nehru wanted to implement had long been part of the Congress agenda. Land reforms, zamindari abolition, nationali-sation of the core sector of industry and reservation for backward classes in education and employment had been part of the resolutions at the annual meetings of the Congress party from the 1930s. However, all these flagship initiatives had ground to a halt because the Fundamental Rights guaranteed in Part III of the Constitution gave the zamindars, the industrial magnates (who also controlled the press) and the educated elite the ability to challenge legislation. From the RSS-backed Organiser to the left-leaning Crossroads, the government of the day was subjected to intense criticism. It took recourse to the relevant sections of the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act (in the case of Crossroads) and the East Punjab Public Safety Act (in the case of Organiser), but both were declared void by the Supreme Court on account of their violation of the Right to Freedom of Speech.

Regarding zamindari abolition, the Allahabad High Court had passed a series of injunctions restraining the government from taking any action against the newly passed Zamindari Abolition Act while it examined its constitutional validity. Likewise in Bihar, the State Management of Estates and Tenures Act had been declared ultra vires of the Constitution by the Patna High Court as violative of the (then) Fundamental Right to Property guaranteed by Article 31, and the Right to Equality under Article 14. While the nationalisation of road transport in Bombay was not struck down, the CP & Berar legislation on bidis was declared inoperative as it violated the right to carry on any trade or profession. In Madras, the caste-based reservations in educational institutions were struck down by the Madras High Court with the observation that Article 15 (1) prevented discrimination based on caste, communal and racial grounds. This decision was upheld by the Supreme Court as well, and the government was left red-faced.

India was now in the fourth year of her independence, and the Congress government had not been able to make any substantial difference to the lives of the people on the ground. On the other hand, the belligerent criticism from the press went on unabated. By early 1951, Nehru wrote to his chief ministers that “it is impossible to hang up urgent social changes because the Constitution comes in the way. We shall have to find a remedy, even though it might involve a change in the Constitution.” Thus, within a year of adopting the Constitution, Nehru and his colleagues felt the imperative need to change it – for it was perceived to be a roadblock in the implementation of the social and economic agenda of the Congress. However, the proposed changes were so pervasive and all-encompassing that Prof Upendra Baxi went on to characterise it as the Second Constitution!

The First Amendment was introduced by Prime Minister Nehru himself and sought changes to Article 19 (a), freedom of speech, Article 19 (g), freedom to practise any profession or trade, and Article 31, right to property. It also sought to strike a balance between Article 15 (Fundamental Rights) with Article 46 (Directive Principles).

The opposition to the proposed amendment was quite intense – both within and outside Parliament – and even within the Congress parliamentarians, there was reticence and concern. Singh documents the fact that even President Rajendra Prasad wanted Nehru to reconsider the provisions regarding freedom of expression, as well as the procedural aspect of carrying out an amendment even as the two houses of Parliament, the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, were yet to be constituted. Nehru himself acknowledged in his letter to Bidhan Chandra Roy that “the bill for the amendment to the constitution is meeting with a good deal of opposition in the press and elsewhere” but went on to add that “we hope to get it through, even though it requires a two-thirds majority”.

The opposition to the proposed amendment was quite intense – both within and outside Parliament – and even within the Congress parliamentarians, there was reticence and concern. Singh documents the fact that even President Rajendra Prasad wanted Nehru to reconsider the provisions regarding freedom of expression, as well as the procedural aspect of carrying out an amendment even as the two houses of Parliament, the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, were yet to be constituted. Nehru himself acknowledged in his letter to Bidhan Chandra Roy that “the bill for the amendment to the constitution is meeting with a good deal of opposition in the press and elsewhere” but went on to add that “we hope to get it through, even though it requires a two-thirds majority”.

Well, the Congress had the majority and Nehru held complete sway over the party. As his biographer, S. Gopal, wrote, “He had the eager subservience of mouldering mediocrities who claimed to be his colleagues.” Yet the opposition was able to put up a valiant fight. Led by stalwarts like Shyama Prasad Mookerjee, Acharya Kriplani, H.N. Kunzru, Nasiruddin Ahmad, Ram Narain Singh, K.T. Shah, Hussain Imam and Hukam Singh, they questioned the timing, the intent, and the procedural shortcomings. They were joined by Congress rebels and dissenters like Shibban Lal Saxena, H.V. Kamath, K.K. Bhattacharya, Damodar Swaroop and Sucheta Kriplani. They also had the support of the tribal leader, Jaipal Singh, who captained the Indian hockey team which won gold in the 1928 Olympics.

Singh describes the debate between Nehru and Mookerjee – both very powerful speakers, and erstwhile colleagues in the Union cabinet as fierce, rabid and ‘no-holds-barred’. The Times of India described the verbal duel between them on June 2, 1951, as “an intemperate and impassioned slanging match between the Prime Minister and Shyama Prasad Mookerjee”. While Mookerjee felt that this was the death knell of freedom and liberty, Nehru held that the reforms were necessary to usher in the dynamic ideas of social reform and social engineering, enshrined in the Directive Principles of State Policy as guidelines for the newly independent state.

While the book draws all its material from records available in the English-language press and the proceedings of Parliament, the flavour of the local press and the pro-government newspapers is not given adequate space. The fact is that there was overwhelming ground-level support for land reforms as well as for reservation in educational institutions and government jobs. Compared to the English-language press, the regional papers were in favour of land reforms, nationalisation and reservation. The elite who occupied the topmost echelons of industry, media and judiciary were obviously not very much in favour of the reforms as they were hurtful to their economic interests and political clout.

In fact, the First Amendment made it clear that while the judiciary was there to interpret the law, the law itself could be changed by Parliament at the behest of the executive!

(The author is a historian, public policy analyst, and Festival Director at the Valley of Words, Dehradun. Until recently, he was the Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie.)

(The author is a historian, public policy analyst, and Festival Director at the Valley of Words, Dehradun. Until recently, he was the Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie.)