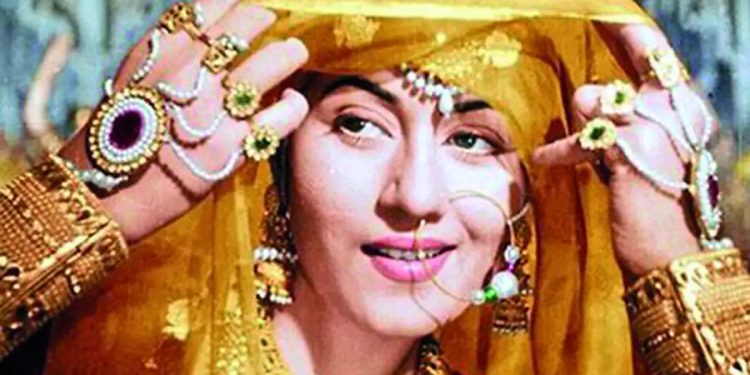

Two illustrated books on legendary themes, the first on the 1960 film classic Mughal-e-Azam, and the next on Mahatma Gandhi as portrayed in art, make for delightful and educational reading

By Sanjeev Chopra

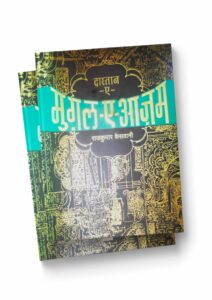

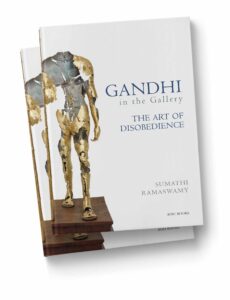

These are not the typical coffee-table books with excellent pictures and photographs on fine art paper, in which a picture is expected to speak a thousand words. These are also not academic tomes without any human interest, where the text is interspersed with illustrations to break the monotony. These are professionally researched, beautifully printed (or, if one may use the term, crafted) editions in which the fine selection of paintings, sketches, photos, posters and calendars is embellished by professionally researched text which embellishes the illustrations, and vice versa. Let us call them ‘illustrated context books’, to distinguish them from other kinds of books with illustrations and text, such as the textbooks and coffee-table books. This column will focus on two such illustrated context books: Dastan-e-Mughal-e-Azam, by Rajkumar Keswani, and Gandhi in the Gallery: The Art of Disobedience, by Sumathy Ramaswamy, which have made it to the short list of the Valley of Words awards, 2021.

Dastan is the story of Lahore, Bombay, Calcutta, Benares and Azamgarh, and of the famous personalities of the world of art, music, cinema and theatre who gave a certain and definitive direction to these genres.

Before I discuss Keswani’s magnum opus, which, like the movie itself, took more than a decade to document, a few words about the author. Keswani started his journalistic career as a subeditor for Sports Time and went on to write for the Illustrated Weekly of India, Dainik Bhaskar, Sunday, New York Times, India Today and the Week. In fact, he had been trying to alert the authorities to the impending gas leak disaster in Bhopal for two years before the actual incident took place in 1984. Unfortunately, Keswani succumbed to COVID-19 on 22 May this year, eight days before the announcement of the Awards.

Dastan is in many ways a chronicle of the century that just went by. It is the story of Lahore, Bombay, Calcutta, Benares and Azamgarh, and of the famous personalities of the world of art, music, cinema and theatre who gave a certain and definitive direction to these genres. We learn, for example, that the movie was inspired by a play: Anarkali, first enacted in Lahore in 1922. Written by Imtiaz Ali Taj, it became immensely popular on the radio, and Munshi Premchand said that this had been the most engaging drama he had heard so far! It inspired a silent movie The Love of a Mughal Prince, in which Anarkali was enacted by Sitara Devi and Akbar’s role was performed by Taj himself. Two other versions of the Anarkali story — by Prafulla and Charu Roy, and Ardeshir Irani — also appeared in quick succession. All made money and brought considerable fame to their producers. By 1935, silent movies gave way to ‘talkies’, and Anarkali was a hit yet again.

“The book is also the story of the dreamy-eyed K. Asif, the son of a doctor, but apprenticed to a bespoke tailor who set up shop in Bombay as a ladies’ tailor. His storytelling technique got him an entry into the world of cinema.”

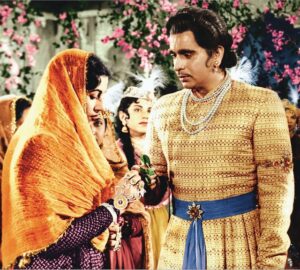

However, in the hands of K. Asif the story had a director who believed that the legend of Anarkali had to be seen on a spectacular scale. The zeitgeist had to be captured, therefore he planned to make a movie on the great Mughal in which Anarkali had a role, a significant role, but as part of a wider setting. This story, he decided, had to be seen from several viewpoints — those of a lover, a mother, an emperor and a friend. The first attempt at making this film, starring Nargis, Chandramohan and Veena, was abandoned as the producer Shiraz Ali Karim left for Pakistan in 1947. However, Asif did not give up. He convinced Seth Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry to take over as the producer. Mistry had only one condition: Prithviraj Kapoor should play the role of Akbar, and Asif promptly said ‘yes’. Dilip Kumar was chosen for the role of Prince Salim, but the search for Anarkali was made across the length and breadth of the country, with newspaper advertisements and announcements asking girls to audition for the role. Although most cinema-focused papers thought that the role would be given to Nutan, eventually Madhubala was selected, because Dilip Kumar had more than a soft corner for her.

The book is also the story of the dreamy-eyed K. Asif, the son of a doctor, but apprenticed to a bespoke tailor who set up shop in Bombay as a ladies’ tailor. His storytelling technique and ability to weave dreams soon got him an entry into the world of cinema. He made his directorial debut at the young age of 21, when he directed Phul. Then there was no looking back, and he moved on from movie to movie, and one relationship to another!

Dastan also takes us back to the first few years of our independence when the rupee had 96 paise, giving rise to the expression ‘solah anna sach’ — true as 16 annas — with each anna having six paise. There were coins called ‘chavanni’, four annas or 24 paise, and atthanni, eight annas or 48 paise. Asif would always travel around in a cab, the black and yellow taxi, which was also called the ‘six anna ride’, because each mile would cost the passenger this princely sum of money. The new Indian rupee came into existence when India shifted to the decimal system in 1956.

Another notable feature of this book is the 25 plates made by M.F. Husain. These have great value, for they show images from the sets of the movies, especially images of the sculptor chiselling the fine statue, and Anarkali in conversation with Akbar-e-Alam.

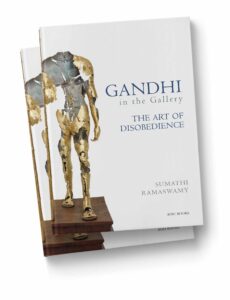

Husain is also prominently featured in the second book Gandhi in the Gallery: The Art of Disobedience, by Sumathy Ramaswamy, in which Gandhi is the muse for at least three generations of artists — starting in 1917, when his portrait was painted by Mukul Dey, and on to the montage by Pinak Bani in the Swatantrata Sangrama Sangrahalaya (Museum of the Freedom Struggle) in 2017. Ramaswamy has painstakingly captured the perceptions of Gandhi in the hands of the painters, sculptors, artists and lensmen, not just during his life but also in his afterlife. Has the essence of Gandhi ever been captured? As she says, “He is seemingly visible everywhere, but nowhere really to be seen, his complex ideas reduced to empty platitudes, and his radical disobedience tamed and tempered.” Gandhi was never a conformist, even if those who dislike him immensely still make use of his name, words and image. Knowingly or unknowingly, wittingly or otherwise, Gandhiji inspired a generation of artists who looked upon him in many ways. For the Indian National Congress and those involved in the freedom movement, he was a sage, a mahatma, a father figure, an inspiration and an icon to be followed. This was also the official image of the Mahatma which the emergent nation projected to her citizens and the world. The Indian currency carries no other image, and all governments, cutting across party lines, have invoked his name and blessings. Then we have perceptions of Gandhi which his antagonists had, from Jinnah to Churchill to Ambedkar — whose followers reject Gandhi’s term ‘Harijan’ and position him as an upholder of the Varnashrama Dharma, or caste system. Be that as it may, he was one of the most important figures of the first half of the 20th century from the time of his arrival in India from South Africa to his death by an assassin’s bullet in 1948.

Gandhi in the Gallery has so many images of him: as an icon of nonviolence, apostle of peace, leader of a mass movement, advocate for the charkha, at the helm of the Salt March. We see him in a barrister’s robe, capture his meeting with the King-Emperor and his famous fasts. We see the 21st century imagination at work with Gandhi working on a laptop and walking a dog. There is also a digital montage by Pinak Bani which is rabid in its critique of Gandhi. Here, among the worldly remains of the Mahatma, are exhibited one fourfold pyramid, representing the Varnashrama Dharma as well as a pure lead bar — molten lead is to be poured in the ears of the Shudra who dares to access the knowledge reserved for Brahmins.

If the themes are varied, so are the eclectic and wide-ranging formats of expression. We have chromolithographs, watercolour on canvas, mixed media on paper, acrylic on canvas, photographs, images, inkjet prints, casein and pigment on canvas, tempera on card and black pencil on paper, bronze busts, woodcuts, plaster of Paris figures, murals, enamel-painted metal roller shutters, acrylic and marble dust on canvas… There are first-day covers, postage stamps and calendars, as well as the ubiquitous statues and framed icons that one sees across the roads and streets of this country.

One can spend time with each of the illustrations — and every time one set is juxtaposed with another in terms of themes, timelines and mediums, one is struck by the new voices and dialogues that one encounters. In fact, the cover page, which shows the ‘hollow of the hallowed’ with a ‘firm grip on the staff’, sets one to thinking about the man whose head is not shown, but whose direction of forward march is clear! Hats off to the writer as well as the publisher for this wonderful gift on the life and afterlife of the great icon of nonviolent disobedience — the Mahatma!

Books At a Glance

Title: Dastan-e-Mughal-e-Azam

Author: Rajkumar Keswani

Publisher: Manjul Publishing House

Pages: 391

Price: Rs 1,599/-

Title: Gandhi in the Gallery:

The Art of Disobedience

Author: Sumathi Ramaswamy

Publisher: Roli Books

Pages: 216

Price: Rs 1,044/-

(The author is a historian, public policy analyst and Festival Director at the Valley of Words, Dehradun. Until recently, he was Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie.)