A folk art form practised by women in Bihar that gained worldwide recognition in the 1960s

By Kumud Das

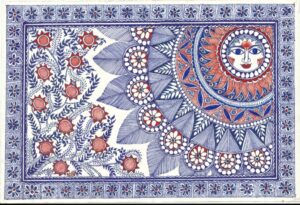

Mithila art is known around the world, most commonly as Madhubani painting, the folk-art form from Bihar that is now a household name for art lovers everywhere.

It is deemed to have originated in the kingdom of Mithila, ruled by Janaka, Sita’s father in Valmiki’s Ramayana. The area falls in present-day Bihar. It is a popular Indian folk art form, practised mostly by women and meant as a religious offering. Mithila paintings are characterised by line-based patterns, a form that is said to trace back to the anecdote in the Ramayana in which Lakshmana, the younger brother of Rama, drew the famous Lakshman Rekha for Sita, outside her dwelling.

If one visits a home in this region where a wedding is to take place, one will see the kohbar, or nuptial chamber, decorated with these paintings. The images are based on mythological and folk themes as well as tantric symbolism. The central themes, invariably, are love and fertility.

The credit for taking this art form to the outside world goes to the British of the Raj. They discovered it after an earthquake in 1934. Most Mithila art is done as wall murals. The colours are created using natural products like vegetable dyes. Sketches are prepared using the ‘karchi’ (bamboo twig), and depict gods as well as flora and fauna.

What we know as modern Mithila painting was born in the early 1960s, following a terrible famine in Bihar. Women living in the region applied their painting skills to a new medium, paper, to bring in a living. They had painted the walls of their huts for centuries and their work had remained unknown to the outside world; now, on paper, it could travel the world.

Mithila painting entered the limelight during the early years of the current century. Art dealers, museums, exhibitions, and scholars the world over have helped it gain wide publicity. Still, the tantric art style of painting which uses natural vegetable colours for creations is fast losing its sheen in its home territory of Mithilanchal, in northern Bihar. Even people of the region now shy away from putting up Mithila paintings inside their houses.

For connoisseurs, Mithila art is aesthetic, authentic and pleasant, primarily due to its visual discipline and underlying stories.

Godawari Dutta, who was conferred a Padma Shri, the fourth highest civilian award in the country, in 2019 for her contributions in the field of Mithila painting, says that it is this art which made her a globetrotter and earned her fame. She is well versed in the Kayastha style of Mithila painting that favours black and white contrasts. Unlike other artists, she uses bamboo sticks to paint. Recurring themes in her art are portrayals of characters from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, as well as events of daily life like weddings or dances.

“Whenever I make an aripan,” which is a pattern drawn with rice paste and sindoor or vermilion on the floor, “I feel that Saraswati [the goddess of knowledge] is sitting next to me,” she says.

“There is a big change which has happened [in Mithila art] over a period of time. Initially, it was just line painting. Later, colour paintings were introduced as per demand. The art was made by the upper-caste women only, but now it is made by women from different castes. Interestingly, marginalised people have joined the bandwagon as well, and thus become financially strong, which is a positive development,” says Dutta.

She has faced obstacles in her life. But she is happy that, with determination and patience, she has come out of adversity. She has visited Japan seven times, staying there for six months to a year. Works she created during those visits are now owned by the Mithila Museum in Takomachi and the Fukuoka Art Museum in Japan.

Mithila art is broadly present in three forms, known as Bharni (coloured), Katchni (line sketches) and Godna (a kind of mandala done in concentric circles).

Practised mostly by Brahmins, Bharni combines relatively sparse linework with solid-colour infill. Katchni is popular among Kayastha artisans and can be easily recognised because of the rectilinear and curvilinear lines of different widths and colours used to depict gods. Artists from comparatively lower castes (Dushadhs, in particular) use the Godna style, in which shapes and figures are outlined in black paint using nib-pens. The Mithila Museum in Japan holds several Godna artworks by Dalit artists. Interestingly, Dulari Devi, this year’s Padma Shri recipient, who hails from the marginalised Dalit Mallah caste, has adopted Katchni and Bharni styles rather than Godna.

Gods and goddesses chosen for depiction are taken generously from within the capacious boundaries of Hinduism: Shiva, Durga, Rama, Sita, Krishna, Vishnu and Kali may all figure. Goddesses, like Durga, Saraswati, Kali and Naina Jogin, are as prevalent as gods like Rama, Krishna, Vishnu and Shiva.

Shashikala Devi, another renowned Madhubani artist, says that although she herself has never used artificial colours, contemporary Mithila artists don’t hesitate to use even fabric colours for their work. She also says that she has never worked for commercial gain.

Most Mithila artists share a couple of remarkable characteristics. Most of them are formally unschooled, even if they have earned name and fame at a global level with their art. Second, these artists don’t hesitate to respond, in their works, to the various modern conflicts that confront their changing society.

Renowned artist Ravindra Kumar Das says that Mithila painting has an edge over other forms of folk art in the country, the credit for which goes to art-lovers from abroad who recognised the significance of the art form. They did not hesitate to invite Mithila artists direct from their doorsteps in the Mithilanchal to distant countries in the Western world.

What are the tools used by Mithila artists? They use a variety of traditional tools besides their fingers, such as twigs, brushes, nib-pens and matchsticks, and they use natural dyes and pigments. There is ritual content for particular occasions, such as births or weddings, and festivals such as Holi, Diwali, Surya Shasti, Bhratri Dwitiya and Dussehra.

“We are working on a book that provides commentary and reflections on, and descriptions of the centuries-old Mithila art tradition. One may ask, why do we need yet another book on an art form when there are so many authoritative books? Well, art is a reflection of humanity. As humanity changes, so does art and its role in our lives. For example, the story of Bharund [shown and described in this book which has chapters from scholars from three continents] perfectly describes for me the constant battle we all have to fight with the many distractions that the modern world provides,” says Minu Agarwal (Adjunct Assistant Professor at CEPT University, Ahmedabad) who has co-edited Mithila Art: A 360 Degree Review of Madhubani Painting, coming out this year.

(The author is a senior journalist.)