Ramesh Inder Singh who served in Punjab during the 1980s and mid-1990s recapitulates the turmoil in the state in its sheer starkness

BY DR SANJEEV CHOPRA

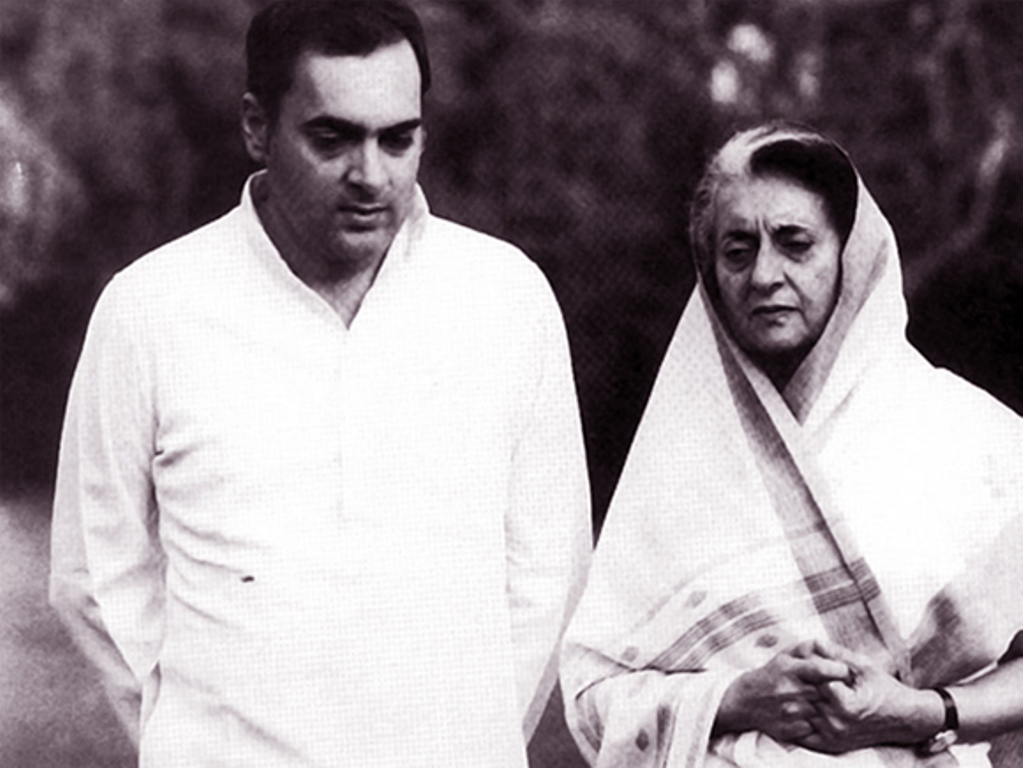

The magnum opus, Turmoil In Punjab ~ Before and After Blue Star ~ An Insider’s Story, by Ramesh Inder Singh is much more than the narration of the most difficult 15 years of Punjab: from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, which included Operation Blue Star, the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and its aftermath across the country, including Punjab. It is also a story of the breakdown of the civilian hierarchy, competitive politics, misplaced bravado, electoral compulsions, broken promises and the failure of the political leadership at the helm to respond to grievances in time. As late as March 29, 1984, Rajiv Gandhi called Bhindranwale a religious leader and argued that the police should

not enter the Golden Temple. Under such circumstances, he was also making it difficult for the Akalis to oppose Bhindranwale.

However, two months later, on June 2, 1984, in a broadcast to the nation, Mrs Gandhi talked about the situation in Punjab, spoke about the need for a dialogue, but in the same breath announced that the Army would be moving into the state. However, neither the President of India, the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, nor the top echelons of the Ministry of Defence, including the serving chief (Gen. A.S. Vaidya), and the Intelligence Bureau (IB) were actually aware of the confabulations between the prime minister and the Western Army Commander, Lt Gen. K. Sundarji.

A day later, Ramesh Inder Singh was literally catapulted into Amritsar as the deputy commissioner without the chief secretary or home secretary briefing him. The same evening, at 5 pm, Gen. K.S. Brar reached Amritsar and took charge of the operation and convened a meeting with the civil and police administration as well as the Border Security Force (BSF) and the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), who had not been briefed about the decision to hand over the operation to the Army. For all the bravado and pluck, the army commanders lacked an appreciation of the on-ground conditions but, more importantly, showed a noticeable disinclination to take the administration on board. Gen. Sundarji, who liked to think of himself as a strategist, had given a commitment to the political leadership that in a blitzkrieg operation with elements of speed and surprise, he would be able to flush out the terrorists in a matter of hours and that the sanctum sanctorum would not be damaged. However, his lack of knowledge of the precincts of the Golden Temple and the Akal Takht, and his failure to anticipate the resistance from the cashiered Major General Shabeg Singh led to hundreds of avoidable deaths—of soldiers, militants and innocent bystanders. Incidentally, Sundarji’s propensity to bypass whoever he did not like also became clear during Operation Brasstacks and the fiasco with the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF). This has also been corroborated independently in Wahajat Habibullah’s book on Rajiv Gandhi.

Well, given the might of the Indian Army, Shabeg stood no chance but, as Singh points out, Blue Star was not the epilogue but the prologue to the violent struggle for Khalistan. It is fortuitous that things did not go out of hand but for the record 29,000 troops in various Sikh paltans—the Ramgarh Training Centre in Bihar, the First Sikh, Ninth Sikh at Rajasthan, the Third Sikh in the Northeast, and Eighteen Sikh at Meeran Sahib near Jammu—abandoned their positions, the first time ever in the history of independent India. Although both Mrs Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi insisted that Blue Star was not a blunder, Gen. P.N. Hoon called it “ill-planned, ill-conceived and ill-implemented—a black chapter in the history of the armed forces”

The visits of the President and the PM did not help: It made matters worse. They had no explanation to offer, and no one was fooled by the ‘symbolic’ gestures. They were not given the traditional siropas (traditional welcome scarf ) and after they left, the hymn sung in the Durbar Saheb was from Babur Vani—Nanak’s anguish against the ruler—and it read, “Kings are like bloodthirsty tigers, and their officials are bloodhounds.”

Although the President was able to negotiate a pardon for himself, the government of the day wanted to deny him any credit for the withdrawal of the Army. Punjab had become a garrison state in which civilian authority—starting from the divisional commissioner of Jalandhar to the SDMs and OCs—was placed under the Army, who in turn started with the impression that ‘no one in the civil police and administration could be trusted’. Thanks to the patient and mature handling by officers like Singh and his rapport with the senior Army commanders, many issues were resolved. However, reading the chapter gives one an idea of why Pakistan has descended into the chaos that it is today.

Although Rajiv Gandhi started his term with the unfortunate statement about collateral damage when a big tree falls and an election campaign which was blatantly communal and holding the entire Sikh community responsible for Mrs Gandhi’s assassination, once in power he displayed political sagacity and opened a dialogue with Longowal, conceding most points. The credit for the Punjab Accord and political settlement goes to Arjun Singh, the politically savvy governor who began his short but meaningful innings in Punjab with an oath in Punjabi, and reached out to the Shiromani Gurudwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) and the Akali leadership and S.S. Barnala took over as the chief minister. However, the machinations of Buta Singh continued and the first breach of the Rajiv-Longowal accord took place when Chandigarh was not transferred to Punjab because in an extremely short-sighted, or if one may say cynical, move the focus had shifted to the elections in Haryana and the commitments made to Longowal were set aside, besides placing the state under President’s Rule yet again.

Taking a cue from the botched Blue Star, Operation Black Thunder—a joint operation of the National Security Guard (NSG), paramilitary and Punjab Police in April 1986—was better planned, and even though there were acrimonious moments, including the author threatening to withdraw the state government’s requisition of the NSG, the swift and short operation was completed in less than seven hours. But the key factor was negotiation and involvement of the high priests. The second edition of Black Thunder took place on May 9, 1988 and was even more successful. It resulted in the death of 30 militants and meek surrender of the rest in single file formation with their hands raised above their heads in broad daylight.

We now come to the Gill doctrine—the physical elimination of terrorists without conceding any of their demands. K.P.S. Gill secured political endorsement from Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, Governor Surendra Nath and the newly elected chief minister, Beant Singh. The Gill doctrine included the ‘militarisation’ of Punjab Police—arming it with bullet-proof cars and jeeps with mounted machine guns, LMGs, AK-47s, mine detectors, bomb disposal squads, coupled with the induction of young operational commanders from the CRPF and BSF, and the direct reporting of SSPs to the DGP. The jury is still out on whether there was any alternative to the Gill doctrine, considering that the political leadership—both in the Congress and the Akali Dal—often dithered.

In my view, this book will become an iconic book, much like Joseph Davy Cunningham’s History of the Sikhs: From the origin of the nation to the battles at Sutlej, and Khushwant Singh’s two-volume scholarly study, The Sikhs. Cunningham talks of the origin of the movement, and the consolidation and decline of political authority after the death of Ranjit Singh, and Khushwant Singh takes the narration up to the partition of the country and the establishment of present-day Punjab. Correspondingly, Turmoil… is indeed the book to be read for understanding Punjab in the turbulent Eighties and mid-Nineties, and there was no one who could have done a better job than scholar-administrator Ramesh Inder Singh.

(The reviewer is a historian, public policy analyst, and Festival Director at the Valley of Words, Dehradun. Until recently, he was the Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, Mussoorie.)