Disruptions, shortages and escalating prices due to geopolitical tensions and sanctions have truncated India’s growth story. But growth momentum will be regained as structural reforms are underway…

BY B. SHEKHAR

he unforeseen geopolitical tensions in the East European region have hit the Indian economy as well. At a time when the economy was on a steady upsurge, the Russia-Ukraine war has upset the apple cart for India and growth targets are now slightly downsized.

When it looked like the difficult Covid-19 pandemic phase was over and the global economy was on the recovery path, the Ukraine war has triggered yet another bout of economic constriction the world over. And India is no exception to this sudden economic downturn.

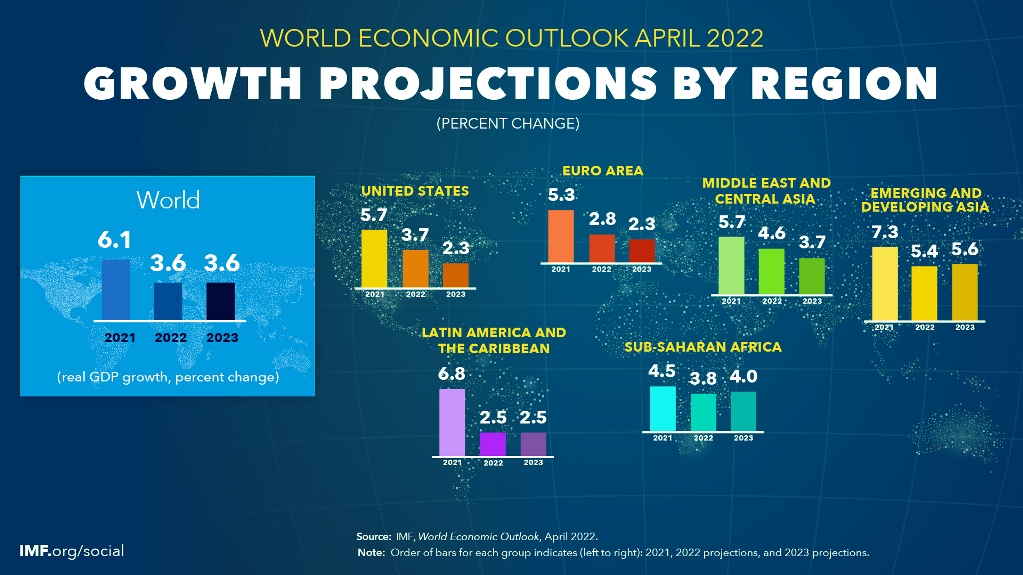

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its latest World Economic Outlook report has lowered India’s GDP growth to 8.2 percent for FY23, from 9 percent for the same period last year. The downgrade in the 2023 growth projection for India is partly reflective of the Ukraine war that has

resulted in high energy and food prices slowing down the growth momentum. Notable downgrades in the forecast for Asia include Japan (0.9 percentage point) and India (0.8 percentage point), “reflecting in part weaker domestic demand—as higher oil prices are expected to weigh on private consumption and investment—and a drag from lower net exports,” the report stated.

The Ukraine war has exacerbated two difficult policy trade-offs: between tackling inflation and safeguarding the recovery; and between supporting the vulnerable people and rebuilding fiscal buffers.

Even as the war reduces growth, it will add to inflation. Fuel and food prices have increased rapidly, with vulnerable populations, particularly in low-income countries like India, ending up the most affected. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in its May 4, 2022 Monetary Policy Statement

indicated that the headline CPI inflation surged to 7.0 percent from 6.1 percent in February, largely reflecting the impact of geopolitical spillovers. Food inflation increased by 154 basis points to 7.5 percent and core inflation rose by 54 bps to 6.4 percent. The rapid rise in inflation is occurring in an environment in which inflationary pressures are broadening across the world.

It is acknowledged that elevated inflation will complicate the trade-offs central banks face between containing price pressures and safeguarding growth. Interest rates are expected to rise as central banks tighten policy, exerting pressure on emerging markets and developing economies like India. This will directly affect the off-take of credit from the industry, thus further shutting off the decision-making process in

boardrooms for expansion or establishing new projects. And the direct effect of this turn-off is that job creation is at stake and the demographic advantage that India has gets wasted due to under-utilisation of human resource capital.

It is again a recognised fact that the transmission of the war shock will vary across countries, depending on trade and financial linkages, exposure to commodity price increases, and the strength of the pre-existing inflation surge. Gauging the impact, appropriate monetary policy

response is required.

Discussing this very point of geopolitical developments at the Spring Meetings in the US, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva raised concerns about its impact on the global economy and the challenges linked to the rising commodity prices due to it. Explaining India’s policy approach, Sitharaman mentioned that an accommodative fiscal stance was accompanied by major structural reforms, including support for industry, particularly MSME and other vulnerable sections.

Going by the statements made by the FM, the central government has announced a customs duty cut on petroleum products which is the key segment to soften inflationary pressure as this has a cascading effect on all commodities.

Similarly, the government also waived customs duty on the import of raw materials, including coking coal and ferronickel, used by the steel industry, a move which will lower the cost for the domestic industry and reduce prices. Also, to increase domestic availability, the duty on export of iron ore has been hiked to 50 percent and a few steel intermediaries to 15 percent. The duty changes have already been effected.

Sitharaman said that the RBI fully supported and complemented these efforts with an accommodative stance. The finance minister further stated that India has been helped by good agricultural output, supported by a good monsoon during the Covid pandemic. Agricultural exports, along with other exports, have also sharply increased. India is entering into new economic activities which will help resolve some of the global supply chain issues.

A very important and extremely bold policy decision effected by India is on the oil front. Despite the threat of US sanctions, the Indian government announced its decision to go ahead and buy Russian crude. “If oil is available and at a discount, why shouldn’t I buy it? I need it for my people,” Sitharaman said last month.

But for India, the decision to hold to its neutrality on Russia’s war in Ukraine is no longer just about keeping its options open in a world with multiple centres of power. It has evolved into a lucrative case of economic opportunism: Russian oil is just too good a deal to pass up.

India’s purchases of Russian crude have soared since the start of the war in Ukraine, rising from nothing in December and January to about 300,000 barrels a day in March and 700,000 a day in April. The crude now accounts for nearly 17 percent of Indian imports, up from less than 1 percent before the invasion. Last year, India imported about 33,000 barrels a day on average from Russia.

With Russian oil banned in the United States and Europe now proposing an embargo of its own, India can buy the crude at substantial discounts, powering its energy-thirsty economy at a lower cost. Indian refiners can also use the crude to make products like diesel and jet fuel and sell it at better-than-usual margins abroad.

As India leverages the war to help fuel its post-pandemic economic recovery, trade with Russia is likely to increase with the conflict dragging on. That could further complicate American and European efforts to choke off Russia’s economic lifeblood and strain US-Indian relations as the two nations seek to work together to counter China.

Many homegrown economists may disagree with the fact that the impact due to the Covid-19 pandemic on the country’s macroeconomic fundamentals has been minimal as compared to the other emerging economies. Due to skilful handling and bold policy initiatives, the country has been able to quickly regain its growth momentum.

There is no denying the fact that no country has a GDP growth rate beyond 4 percent, including the First World economies which are struggling at sub 4 percent growth for the past three years.

Asian Development Bank (ADB) Country Director for India Takeo Konishi said: “India is on the path to a sustained economic recovery, thanks to the vigorous countrywide drive to deliver safe and wide-reaching COVID-19 vaccinations, which helped reduce the severity of the third pandemic wave with minimal disruptions to mobility and economic activity.” He further said: “The Government of India’s policy to improve logistics infrastructure, incentives to facilitate industrial production, and measures to improve farmers’ income will support the country’s accelerated recovery.”

The government in the past year has announced large public infrastructure investments planned over the next two years. This will also encourage more private investment. Together with the PM’s Gati Shakti initiative to improve India’s logistics infrastructure, increased financial and technical support to states to expand capital investment will boost infrastructure spending and help spur economic growth. Private consumption will pick up as labour market conditions improve.

Another important and welcome aspect to note is that the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) has forecast another year of a normal monsoon, which, coupled with rising wheat prices, is expected to boost agricultural output and improve farmers’ income. The government’s production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme will provide a thrust to the manufacturing sector in FY2022 and FY2023.

India may at this point of time be experiencing economic constrictions due to externalities, but it is a temporary phase and a passing cloud. There is no denying the fact that India is still in the reckoning as far as attracting attention from global investors goes. In a few quarters from now, India may acquire the numero uno position as the manufacturing and supply chain hub of the world.

@bshekhar