The heart-warming and inspiring story of the NRI, the OCI and the PIO across the globe

By Amita Prasad

Let me confess at the start that I have never been a non-resident Indian. I have never experienced their joy, their dreams and their loneliness. My exposure to them has been through those marvellous 1960s and ’70s Bollywood films, where the hat-wearing rich uncle used to be back from South Africa or London and make it good looking for and looking after property. There have been many Non-Resident Indian (NRI) friends and relatives too. The Indian diaspora or the NRI has always been a matter of intrigue, a few laughs and admiration in our family and country. We always complained that their ‘clock is stuck’ in the ’60s and they can’t see what progress India has made. However, they were saluted as risk-takers.

A businessman who narrated his story to me some time back had said that he went to the US in the ’60s with eight dollars in his pocket. Now he has money and respect, along with a beautiful American wife and plenty of tales about his success. That generation looking for opportunity abroad consisted mostly of doctors, engineers and professors. When India was wresting its freedom and going through Partition, they sought many shores, bought land, worked hard, and became a community to reckon with. They fought prejudices and made a name and place for themselves. They brought laurels to their country of birth too. The deprivation in the country in 1947 made them strong and resilient.

The NRI is, legally speaking, someone who does not live more than 182 days in the country. The story and status of the NRI have changed during the past 75 years.

From NRIs being lonely and struggling in foreign lands, India now celebrates their achievements with the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas which has accorded them pride of place in the country. The Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) status, another development in the 2000s, provided stronger ties with the homeland. However, very few came back. Swades was a watershed movie in which Shahrukh Khan returns to do something for his country. Based on a true story, the hero gets over his “readjustment” issues. Water, food, power – taken for granted in Western countries – are routine problems here. It keeps them from coming back, they say. But things have started to change slowly. The economy has opened up, visa rules have eased, the business and working environments have become alluring.

No journey is easy, whether in India or abroad. The NRIs are now more connected with their motherland. Technology has brought us closer.

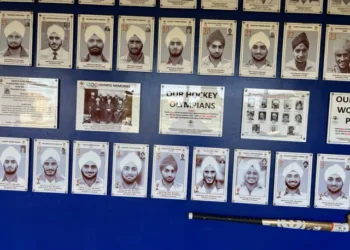

Seventy-five years of independence has seen them proudly unfurling the Indian tricolour at prominent places in their adopted countries. Going away from the motherland was nothing new for Indians. Historically, Indians went to Sri Lanka (for religion), Malaysia and South Africa (for trade), England (to serve the colonial masters), the US (as technocrats), the Middle East (as skilled workers), and Surinam, Fiji, Mauritius (as labour to work on sugarcane farms). These early settlers in foreign lands impacted the culture, traditions, languages and food habits in those places. The samosa and the Ramayana were binding factors. Recently, I met a cab driver of Indian origin in Manhattan whose family had arrived five generations earlier from India in French Guiana. He was proud of his name, Ramsagar, which he could barely pronounce in the Indian way. Both of us were happy to meet and we talked about our roots.

Making a strange place one’s home is never easy. Those who have made it big rouse our awe and inspire us. “Settling” abroad is also a matter of prestige in many communities in India. In some states, like Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, to name a few, it would not be surprising to find that at least one family member is an NRI.

No journey is easy, whether in India or abroad. The NRIs are now more connected with their motherland. Technology has brought us closer. They have joined politics and have become influencers. The curry of India has played a tremendous role in tantalising the taste buds of foreigners. The Indian sari and bindi and Bollywood films have played a yeoman’s role in disseminating knowledge about Indian culture. “Mera Joota hai Japani” has been able to do what no political dialogues could. Indians abroad played it smart and earned a reputation for hard work and non-interference in domestic policies. They are technocrats – part of schools and colleges as teachers, innovators in research and development (R&D) and information technology (IT) projects and being partners in progress. Their contribution has been noted, their culture applauded. With grit and determination they have prospered as doctors, engineers and scientists in their adopted lands.

One question not being asked or answered is why thousands leave India every year. Is it because of nosy bureaucracy which rubs citizens the wrong way, or lack of opportunity? Why do so many students leave for higher studies and never come back? There are Indians in more than 110 countries and they have built their lives there. Many leave India because they just want a happy life, without political trouble and a lack of business ethics. There are stories of ordinary people, who are not from influential families or universities, who have left India for better opportunity. They represent dreams as well as failed promises. Hard-working and strong-willed Indians failing in their motherland are instances of pain and hurt. But they succeed elsewhere. We read the stories everywhere – a taxi driver moved to Singapore and set up a travel agency, a chef moved to Australia and spawned a food chain, a farmer from Rajasthan became a successful farmer in Ethiopia. Each year the number of those leaving India is increasing. Does this migration reflect people’s deep unhappiness with India? It is a difficult question to answer.

However, the newer generation of NRIs are more connected with the motherland. They try to connect emotionally through a network. So, a student going abroad now is better networked. Crowdfunding and crowdsourcing have become popular, thanks to social media. During the COVID pandemic, many groups and agencies of NRIs tried to supply medical equipment through private initiatives. NRIs are worried about corruption and misuse of resources. Indians are experts in these two areas! There is a glaring lack of accountability in our country, which hurts efforts to improve things. Should we despair? The answer is a clear no.

The NRI or Person of Indian Origin (PIO) has been given many rights now. They have investment opportunities here. The workplace boundaries have also blurred due to the pandemic. The contribution of the overseas Indian community is being recognised since 2003. January 9, the date on which Mahatma Gandhi returned from South Africa in 1915, is marked as Pravasi Bharatiya Divas. This important platform helps NRIs to connect. They are being honoured for their contribution in various fields. This is also to appreciate their role in the India growth story. Technology and expertise are the new dollars, which India needs from them.

Now, in 2021, when India is celebrating the Amrit Mahotsav of Independence, let the NRI, PIO and diaspora connect with India, engage with India and its policies, and contribute to India’s growth. There are many opportunities in contemporary India for all age groups – culturally, socially, and economically. Re-engagement is the key along with hard work, sincerity, and loyalty. The experience earned abroad can be successfully utilised here.

As Walt Disney said, “All our dreams can come true, if we have courage to pursue them.”

(The writer is a senior IAS officer. The views expressed are personal)