If cinema is the muse, I’m not worthy enough of its love: Sudhir Mishra

With career spanning decades, acclaimed film director and screenwriter, Sudhir Mishra is by now one of the vintage visionaries in the industry. While he never officially studied film-making, he honed his skills during his time at FTII and gained valuable experience working with eminent directors like Kundan Shah, Saeed Mirza and Vidhu Vinod Chopra in the early 80s. His first film Yeh Wo Manzil To Nahin won the National Award for Best Debut Film. He’s been recognised for his illustrious work with three national awards as well as the Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government.

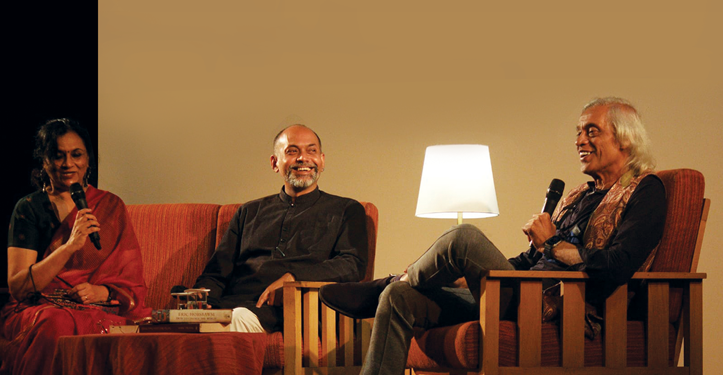

Oroon Das, a multi-disciplinary, designer, curator, and theatre artist, and Sujata Prasad, a former civil servant, author, curator, and heritage conservationist, had a detailed conversation with Sudhir Mishra at the India International Centre, New Delhi recently.

SP: You come from a solid academic background… a Nehruvian mathematician’s son who also had a profound interest in cinema. Part of your lineage is political. Your nana was D P Mishra. You were dabbling with an MPhil in psychology, and doing copious amounts of theatre in Delhi. You were part of Delhi’s third theatre or street, subaltern theatre movement of the heady 70s. You did nearly 500 street shows of Juloos all over the DU campus, in CP, in the bastis and slums of Delhi with M K Raina – creating a direct connect with the audience.

SM: Lots of people were involved with theatre at that time. Vinod Dua for instance, was part of Prayog, an avantgarde theatre group formed by Raina. Then there were Bina Paul, Anamika Haksar and several others. When I walked away to join what was popularly perceived as the corrupt world of cinema, I was called a betrayer.

SP: You have been often caught saying that you grew up with disdain for politics, and yet what you were caught up in was an extremely political theatre movement led by Badal Sircar. You were using theatre as a political instrument, weren’t you?

SM: My disdain was for all the muck that surrounds politics.

SP: What spurred you to cinema? You must have had a multitude of options to choose from. Would it be right to call you an accidental film-maker?

SM: Yes, in a sense it was accidental. Vinod Dua asked me to help him with a show being done for Doordarshan. I met Vidhu Vinod Chopra there. He invited me to work with him in Bombay and the rest is history. I learnt the craft in my father’s lap when he used to take me for screenings at the film society founded by him in Lucknow.

OD: Did you find a literary firmament when you moved to Bombay?

SM: Yes, Bombay was a different place those days. There was a vibrant theatre movement and I was in the company of stalwarts like Arvind Deshpande, Jabbar Patel, Farrukh Dhondy, the poet Adil Jussawalla, Cyrus Mistry, and Vijay Tendulkar. Tendulkar influenced me greatly. I also read a lot. My early life was spent in the fiction section of libraries. Many people say that my work is novelistic! But everything seems to have changed now. I regret that I had to completely leave academics. I hide what I have read to escape being tagged as being over-intellectual.

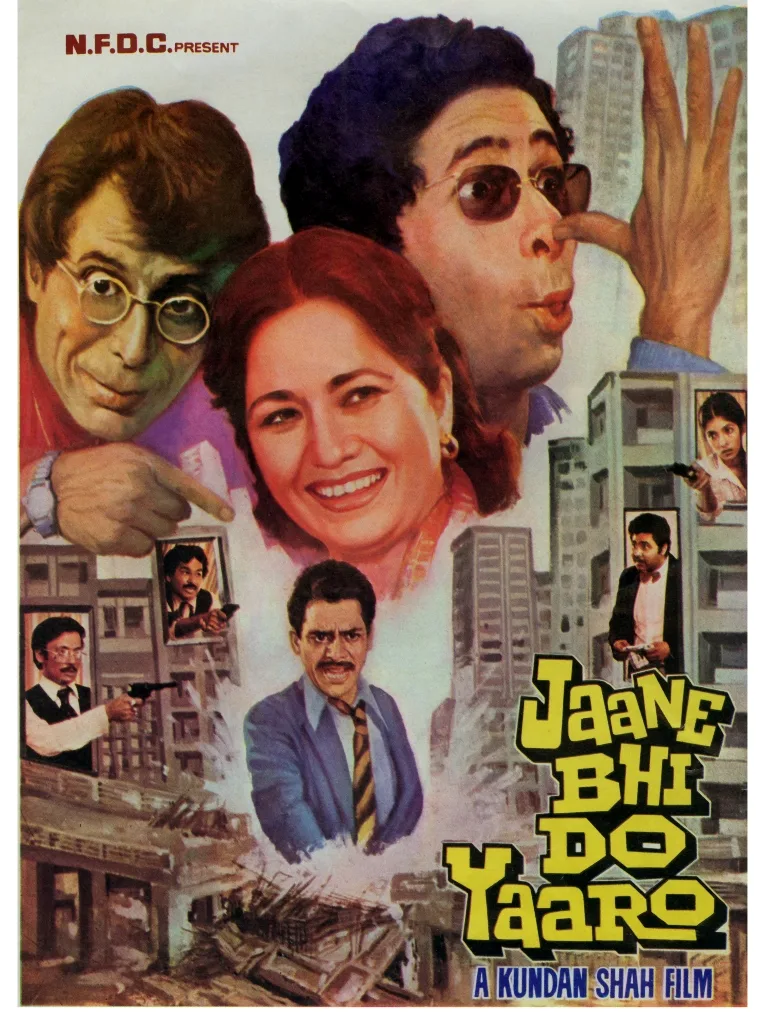

SP: Cut to 1982-83 – to the sets of Kundan Shah’s cult black political comedy Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro – dubbed by Saeed Mirza as an act of celluloid rebellion – a film in which you played multiple roles as the screenplay writer, assistant director and editor. Some of the finest minds came together in the making of the film…for you it must have been nothing less than a masterclass in filmmaking and most certainly in editing.

SM: I was on the sidelines of the film, it was Kundan Shah who was at the centre. I did everything that was expected of me. This included wiping the floor, pushing the trolly, writing the script with Kundan, handing over the tea, waking up the actors, sitting at the editing table…a true masterclass.

SP: Most of the actors were hugely sceptical of the film… Naseer thought it was going to be the worst film ever…but apologised after seeing the first cut. Ravi Baswani said he should have died after the film… He could have become the James Dean of India, a legend. Quite poignantly, Kundan thought of a sequel, but lost interest after Ravi died in 2010.

SM: Yes, Ravi was quite sceptical when I approached him for the film. Kundan, in his terrycot shirt, umbrella, and account book looked more like a Gujarati stockbroker than a filmmaker. Chashme Buddoor had been released and Ravi was quite a star. I knew him from Delhi theatre days and hence managed to persuade him. It eventually brought him the Filmfare Best Comedian Award in 1984.

Om Puri had also got his big break in Ardh Satya. We chased him all the way to the Bandra station and found him standing in the third-class ticket line. He heard the story during the brief train journey and said yes. In some ways, it was a replay of my Delhi days. Most of the actors – Satish Kaushik, Rajesh Puri, Pankaj Kapur, Neena Gupta, Om Puri – were from the National School of Drama.

SP: A film that was so completely irreverent, a scathing commentary on corruption made with an unbelievable budget of Rs 17 lakhs. Isn’t it?

SM: The budget was much less, merely Rs 8 lakhs. I was paid only 4000 rupees for all the services rendered. Kundan tried to save every penny: we travelled all over Bombay using the cheapest public transport, and ate the most ordinary food: in the morning we ate aloo gobhi and in the evening gobhi aloo. The star amongst us was Naseeruddin Shah. He too was compelled to shoot 72 hours at a stretch. Those were difficult days. I was a good assistant to Kundan: when Kundan would say that shooting would stop at 10 at night, I would independently tell the production team that shooting was likely to go on all night. And it would…

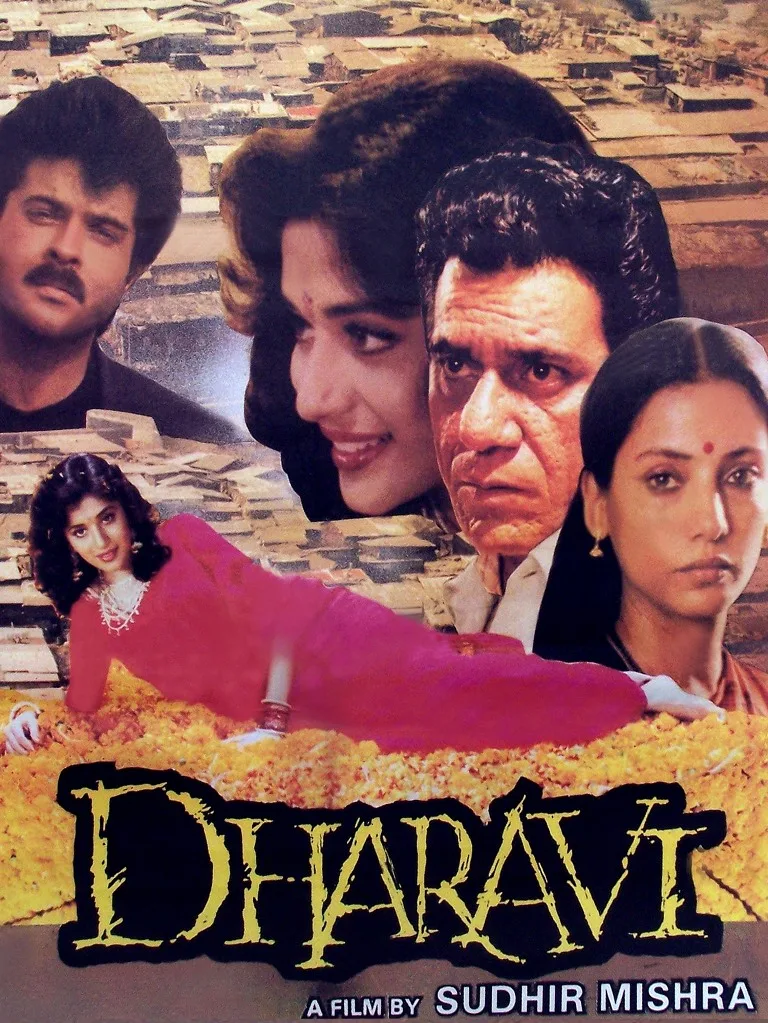

But I must admit that it was a dream period of NFDC. It was in the 70s and much of the 80s, a wonderful, autonomous body committed to the promotion of excellence in cinema. When I made my first film, doyens like Shyam Benegal, Shashi Kapoor, Aravindan, Gautam Ghose, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Basu Bhattacharya were in the NFDC’s board of directors, with Hrishikesh Mukherjee as the chairperson. There was a managing director named Malati Tambay Vaidya who was extremely supportive. My 1992 film Dharavi was one of the last well-known films of that golden phase.

SP: Let’s talk about your intensely profound, poetic, political film, Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi – in a sense an autobiography of our times. Extremely important in these times of amnesia. The film with its beautiful music, cinematography was incredibly nuanced and non-didactic in its treatment of the complex history of the movement. I still remember my first viewing and the intensity with which the film spoke to me not only politically, but also as a woman. You have often said that you identify most with Gita, the female protagonist. I am reminded of what Virginia Woolf wrote about the androgynous mind…it is resonant, porous and the most tuned to creative freedom.

SM: I accept the fluidity that this implies. Let me tell you a story. Many years ago, when I was very young, I went to New York with a bunch of friends. We were told that Gabriel Garcia Marquez was in town. We started chasing him in book-stores and restaurants. We finally found him and hung out with him in a coffee bar. Amongst other things he shared that the mantra of writing female characters was to understand that they are as capable of betrayal as the male characters.

SP: Can we take a pause and talk a little about your personal life – and about the woman in your life, your partner Renu Saluja – a three-time national award-winning editor who edited films like Ardh Satya, Parinda, Dharavi, Bandit Queen, and Saeed Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho, amongst a host of other seminal films. In some senses she was like the female protagonist of the film – feisty, confident, with an indomitable spirit.

SM: Yes, quite a bit. She was independent, brilliant, supremely confident. Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro is a cult classic because of her. I did not know how to write – I was barely 22. Editing is the final stage of the scripting of a film, she made it the most important. I was at the editing table with her as her assistant.

SP: Let me swerve back to another remarkable film, Serious Men, adapted from Manu Joseph’s novel. Made in 2020, it won the Filmfare OTT Awards for best film and best actor. The movie brings out the pain and angst of a man’s desperate attempt to break the frozen caste and class barrier, a role essayed perfectly by Nawazuddin Siddiqui.

SM: My protagonist has the right to dream, the right to make choices, even somewhat wrong ones. In his aspirational quest to take a generational leap, he draws his son into a game of deception…

OD: Where do you locate yourself in the industry?

SM: On the fringe, but the industry side of the fringe. I have many friends in the industry. I survived in Bombay because of the grace and generosity of people like Saeed Mirza, Kundan Shah, Shekhar Kapur, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Ketan Mehta, Javed Akhtar and Mahesh Bhatt. I still meet them but may be not so frequently.

OD: You have been difficult to catch in terms of your affiliations and allegiances. You seem to have pretty much dodged everyone.

SM: This could be due to the early influence of a mind like Badal Sircar’s. I gathered what the real left ideology was by reading authentic Marxist literature and not just pamphlets. I understood that the Bolshevik Revolution was just a coup, so when the Berlin Wall was broken, I was not heartbroken. As a filmmaker you learn to constantly question. I question even myself and feel that if cinema is the muse, I am not worthy enough of its love.