There are glitches and hurdles aplenty on the way, but people and governments can reach out to solutions to speed the process of inoculating the 90 crore

By Dr O.P. Yadava

The coronavirus pandemic has struck unsuspecting humanity with the force of a lightning bolt. We were caught totally off-guard. In too many instances, our response was paralysis. Just as when all seemed to have been lost in this apocalyptic scenario, the medical scientific community rose to the occasion by innovating effective vaccines against the novel coronavirus in record time.

India, too, did well to manufacture two ‘made in India’ vaccines relatively early in the course of the pandemic, and launched the world’s largest vaccination drive against COVID-19 across 3,006 vaccination sites in the country on 16 January 2021. The government laid out a tiered vaccination programme, starting with frontline workers, followed by 12 crore seniors aged 60 and up, then 20 crore residents aged 45–60, and now a whopping 90 crore residents above 18 years of age.

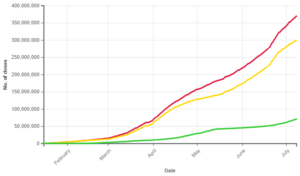

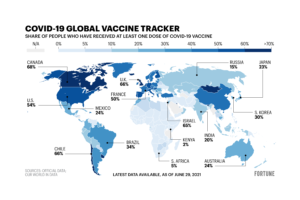

As of 3 July 2021, at the time of going to press, India had administered 34 crore doses of COVID-19 vaccines and 66.2 lakh people had been fully vaccinated with both doses (Fig. 1). Though India ranks in the top five countries of the world in the absolute number of vaccine doses administered, considering the percentage of the population vaccinated, these impressive numbers pale when compared to those of other nations. Israel, for instance, has vaccinated upwards of 50 percent of its population (Fig. 2).

India was one of the early countries to begin its vaccination drive, but we got complacent. In the first months of 2021 we came to believe that we had conquered the coronavirus. This was indeed a major lapse, and a significant contributor to the scale and miseries of the second wave. To make matters worse, the skewed and flawed government policy of asking the private sector and the states to acquire vaccine doses directly from manufacturers ensured that the vaccination drive stuttered badly. Certain states, especially those ruled by Opposition parties, repetitively flagged the shortages in vaccine supply and even alleged that the union government was wilfully squeezing supply, which, obviously, the government vehemently denied. The government did make amends later, once again assuming the responsibility of procuring and supplying vaccine doses to the states at zero cost. Even lactating and pregnant women have now been covered. Hopefully, children will be next, once ongoing international trials confirm the safety of vaccinating them. All these actions, however, came a bit too late to stop the horse of the second wave bolting. Nevertheless, better late than never.

Notwithstanding the government awakening, delayed as it was, there are still some issues with the progress of vaccinations in India. They include the emergence of mutant strains; inequitable distribution of vaccine doses, both in terms of the rural-urban divide and with vulnerable groups unable to compete for access with privileged groups. Opening up the vaccination programme to the 45-plus age group from 1 April, and to the 18-plus more recently, has disadvantaged high-risk and elderly residents. Urban youngsters have smartphones and good Internet connectivity, and they are Net-savvy. Therefore, they are better adapted to corner the elusive vaccine appointment slots online. Even the drive-through vaccination programmes have ensured that a lot of vulnerable individuals, especially senior citizens and the underprivileged, get sidelined from the vaccination drive. Another bottleneck pertains to allegations of favouritism in vaccine supply towards states ruled by the dominant Bharatiya Janata Party, as against those ruled by Opposition parties. The sub-optimal maintenance of the cold chain for vaccine storage and transport is yet another bottleneck, in view of the limited (around 30,000) cold storage facilities, often plagued by power cuts and transmission faults.

The roll-out of vaccination in the rural areas has not picked up, neither from the government’s side, where the delivery mechanisms are not very robust, nor from the patients’ side, because of vaccine hesitancy. The government has not done much to tackle this hesitancy, even though the supply of the vaccine has improved.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has flagged three key reasons for vaccine hesitancy:

Lack of confidence in the vaccine, courtesy a false narrative floated for nefarious political one-upmanship by various political parties, especially those in the Opposition.

Complacency, where the government itself is the prime culprit, and the

Logistics of vaccine availability, another off-shoot of the powerful central government’s vaccine policy.

Recent reports of complications like post-vaccine myocarditis in the young, albeit rare, also have dented the resolve of people to get vaccinated. In developing countries, and countries as diverse and heterogenous like India, matters get complicated further by the social, linguistic, religious, educational, geographical and cultural diversities. To top it all is the gross mistrust amongst the various stakeholders, especially the Centre and the States in the federal structure of governance. Thus, amongst myriad issues, India’s biggest challenge will be to bridge this trust deficit, with a view to improving the vaccine acceptance rates, and to mobilise the bourgeoisie to go to vaccination centres.

The unrealistic, low pricing of the vaccines, too, may surreptitiously play spoilsport. In the current scenario of all-round misery and general pessimism, however, any talk of profit margins may be considered sacrilegious, so manufacturers have been raising these issues in hushed tones. These are real issues, and ethical too, and must be addressed in letter and spirit, so that vaccine availability is not thwarted on some unsubstantive grounds.

“Until we have the vaccine jab available to all of us, let us make use of the next best, and that is the behavioural vaccine: double-masking, 2-metre distancing and frequent handwashing”.

Despite significantly improved vaccine delivery, achieving the number of vaccinations required to mitigate the third wave in India looks, at this moment, a remote possibility. With a population of 90 crore above 18 years of age, we need at least 1.8 billion doses. The availability of the two Indian vaccines in June 2021 was 11 crore doses per month. At this rate, India will take 12–18 months more to vaccinate the entire eligible population.

To answer this challenge, the government has taken steps to boost vaccine availability by placing advance orders with the two Indian manufacturers, paying them upfront to expand production capacity, banning the export of vaccines and recognising international vaccines for use in India. Thus, Rs4,500 crore was sanctioned with a view to increasing the Serum Institute of India’s Covishield vaccine output from 7 crore to 10 crore doses per month by July, and Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin from 3 crore to 5.8 crore doses per month by August. These numbers, augmented by new vaccines approved by the Drugs Controller General of India, give a ray of hope. The total doses expected to be available in 2021 do exceed the target of 1.8 billion doses needed to inoculate all eligible citizens above 18 years of age.

Recently, however, the central government has brought down the estimated availability of the COVID-19 vaccines from 2.16 billion to 1.35 billion doses by December 2021. This includes 50 crore doses of Covishield, 40 crore of Covaxin, 30 crore of Biological E’s vaccine, 5 crore of Zydus-Cadila’s DNA vaccine and 10 crore of Sputnik V. The government has lately gone the extra mile to recognise certain other vaccines from Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna. All these, going forward, should contribute significantly to the pool of available vaccines.

Another important route India can take to boost vaccine availability in quick time is through compulsory licencing. There is a large number of small- to mid-sized units in India that have vaccine manufacturing capabilities but are not equipped for research and innovation. If the two major players release their patent rights voluntarily, or the government does it through the compulsory licencing route, these units can be regulated and supervised to manufacture quality vaccines. Unfortunately, in the government, the left hand knows not what the right hand does! In fact, India and South Africa proposed the intellectual property rights waiver idea before the World Trade Organization, after due diligence, keeping in mind the socio-economic, political and scientific context of the pandemic in the developing world. Even the European Union has backed the IPR waiver. The NITI Aayog, however, contradicted and negated the idea, thereby echoing the interests of the pharma lobby (Pfizer’s expected earnings from its COVID-19 vaccine are $26 billion in 2021) and subjecting the country to embarrassment on the international stage, besides denying the vast vulnerable mass of Indians the easy and affordable availability of a life- and livelihood-saving vaccine.

Compulsory licencing may not be the silver bullet and the nay-sayers may have many a bone to pick, but it would certainly soften the blow of the pandemic for the have-nots of the world. It would nullify to a fair extent the ‘vaccine nationalism’ that the affluent countries of the world have displayed, as they hoard a vast surplus of doses of various vaccines while low-income countries have been able to vaccinate barely 0.7 percent of their populations with even one dose of any vaccine. What better example of inequity and unfairness?

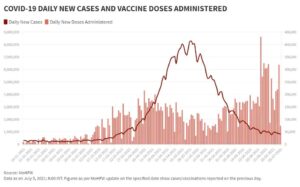

Notwithstanding the relatively rosy picture of improved vaccine availability, the success of the COVID-19 vaccination programme in India now depends entirely on last-mile connectivity. In the new policy, although the responsibility of providing vaccine doses rests with the Centre, the planning and logistics of delivery of vaccines to residents are the states’ responsibility. We need to vaccinate 8 lakh–1 crore people every day to be able to vaccinate the entire 18-plus population of the country by December 2021. We are currently vaccinating 30–40 lakh per day (Fig. 3). Therefore, the infrastructure to deliver these vaccines needs to be ramped up and the private sector should be roped in for this effort. On-the-spot registration is the right way, as this will reduce vaccine wastage, which was occurring earlier with the strategy of providing vaccines only to those with an appointment.

India is at least a year away from reaching anywhere near the 70 percent benchmark of herd immunity. While the USA and certain European countries are now getting back to the pre-pandemic habit days of going maskless in open spaces and the UK is removing legal restrictions on public behaviour, these things remain an elusive dream for us in India. However, India has the capacity to scale up the vaccination drive, as has been shown with multiple campaigns which India has launched successfully in the past, like the smallpox and the Pulse polio vaccination programmes. Even in the COVID-19 scenario, India administered 86 lakh doses on 21 June 2021, which is the highest number for a single day. So, India already has proof of concept, it just needs a little will power and coordination, besides depoliticisation of the vaccination drive, to pull off a truly humanitarian marvel.

Until we have the vaccine jab available to all of us, let us make use of the next best, and probably equally if not more effective alternative, and that is the ‘behavioural vaccine’: double-masking, 2-metre distancing and frequent handwashing. Believe me, these behavioural tweaks are not as obtrusive as we fear, if we think right and make them a habit. Remember when we took to helmets and seatbelts for driving? It’s the same principle. Give it a go! We need to do this for our own sake, our nation’s sake and for the sake of all of humanity on this planet of ours.

(The author is CEO & Chief Cardiac Surgeon, National Heart Institute, New Delhi.)