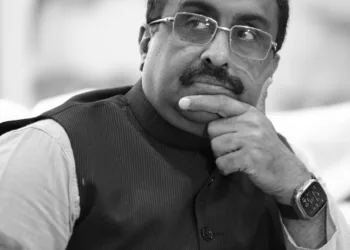

At the 17th Pravasi Bharatiya Divas 2023, held in January at Indore, President Draupadi Murmu presented the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman Award for community welfare to Dr Kannan Ambalam. An associate professor of public administration in Wollega University in Nekemte, in Western Oromia region of Ethiopia, Dr Ambalam has no formal training in civil engineering or water-related issues, but is the man behind various projects in the African country—including construction of 93 bridges, 55 streams, two check dams, a school toilet and electrification of a village.

Inspired to get into community service by his teacher in school, he sought to join the civil service to work for social upliftment. Unsuccessful in the exam, the young man was undeterred. In Ethiopia, he dedicated himself to community service. He works alongside villagers, barefoot like them, and lives with them—eating the same simple food and sleeping in their huts. Dr Ambalam would frequently travel to interior villages, most of the time on foot.

In Ethiopia, he has received recognition from the local communities, from Woreda Offices, Wollega University, and the Ministry of Education. In India, apart from the Pravasi Bharatiya Samman Award, he is a recipient of Zee TV’s Covid Warrior Award and Ananda Vikatan’s Nambikai Manithar Award.

Excerpts from an interview by Pravasi Indians:

Let us begin with your early life…

I was born on June 15, 1977, in Pondhugampatty village, Madurai district, Tamil Nadu, and completed schooling at Government Higher Secondary School, Palamedu, Madurai. My higher education was at Thiagarajar College, Madurai, where I did BSc in chemistry. I joined Madras Christian College for an MA in public administration. Subsequently, I moved to New Delhi and completed MPhil and a PhD from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

In January 2009, I joined Wollega University in Ethiopia as a lecturer in the Department of Public Administration and Development Management. I later became assistant professor and then associate professor. At Wollega University, I served as director, Centre for the Studies of Environment and Society, and vice director of the Corporate Communications Directorate.

And how did you get involved with rural infrastructure?

Along with my teaching responsibilities, I would actively engage the students and the local communities in addressing the pressing problems of rural infrastructure in Ethiopia. Issues such as construction of bridges, micro check dams, water springs, toilets in schools and electrification of villages…

Why did you want to encourage your students to do this?

The purpose of involving students is to shift the knowledge confined in education institutions to social fields for enabling them to have a better understanding of their community’s problems and to equip them with problem-solving skills. It also encourages them to apply developmental concepts and theories in practical situations.

In the context in which you work, all types of resources are limited. How do you cope?

By taking into account the existing socio-economic conditions and to encourage the local communities to build similar projects in other areas, my team and I use low-cost techniques. Similarly, we apply simple technologies by extensively utilising the indigenous and locally available resources. This does away with dependency and also leads to villagers taking pride in solving problems by using their own resources.

Can you trace your inspiration for this work?

I was inspired by my teacher, Kuppusamy, in the government school I attended in Palamedu. He encouraged me to take up community service in the school and its surroundings. He had planted trees. He was interested in gardening. The interest in community work continued during my days in Thiagarajar College, in Madras Christian College and in JNU where I was president of Jhelum Hostel for two terms.

In Ethiopia, what was the very first project you did?

One day, I was in the field with my students to collect research data. We saw a woman struggling to cross a river. With my students, I built a small bridge across the river. It made the local communities so happy. This incident gave me a new energy, a new purpose and mission in life. On our return to class, the students narrated stories of villagers drowning while crossing flooded streams. From that day onwards, I began building low-cost bridges for the communities in Wallega.

You are not an engineer, though.

I am not a professional engineer and I have no formal training in civil engineering or water-related issues. I learned from documentaries on the internet the basics of construction. I depend mainly on my students and local communities for manpower. I draw inspiration from the British civil engineer, John Pennycuick, who built the Mullaperiyar dam in India.

Initially my team and I built wooden bridges but later we upgraded to a composite bridge by blending wood, steel reinforcement and cement. Wooden bridges do not last long due to exposure to sun and rain. Besides, donkeys and horses are mainly used by rural communities to transport their agricultural products to the nearby markets and the animals’ legs would fall into the gaps of wooden bridges. The new cement bridges are fine.

What is the process of a project?

The team visits the project area and holds consultations with the surrounding communities. During these meetings, the issues related to project design, nature of the project, arrangements for resource sharing and schedule for project completion are discussed.

These grassroots-level projects are need-based ‘alternative developmental’ initiatives which mainly rely on creating excellent partnerships with stakeholders, massive participation of local communities and extensively using locally available resources. That means the communities contribute to the construction of the projects by working physically and supplying the locally available materials.

How many projects have been completed so far? What are the benefits?

So far our team has constructed 93 bridges, 55 water springs, one school toilet, two micro check dams, and completed electrification of one village. These projects have a major impact on improving the livelihoods of rural communities. The bridges enable better rural-urban connectivity for the local communities and provide easy access to markets, besides access to medical facilities. Also, people’s income has increased, and the dropout rate in schools has come down. A bridge provides easy access to farmland and grazing grounds on the other side.

If you had to put it in a nutshell, what is the learning from your life’s work?

Use indigenous solutions for problems. Since the villages are located in remote areas, undertaking major construction is costly and hence there are not many bridges for the local communities who have to cross many rivers before reaching the closest urban centres. We have shown how people can come together and build a bridge for themselves and improve their lives.