How a British Asian refugee and his family overcame the challenges of being migrants twice over and what it has taken to rebuild their lives

BY RAM GIDOOMAL

A rich Indian boy turned refugee tells the story of coming full circle to succeed in ways beyond his imagination. Born into a family that fled British India during the partition of India and Pakistan, Ram’s childhood in Mombasa seemed charmed with wealth and success. However, losing all of this overnight through a second deportation, this time from Kenya to the UK, he saw the course of his life change beyond recognition. Starting again from scratch, Ram built a successful career in business. An unusual day trip in Mumbai changed his life forever, transforming him from someone enriching himself and his shareholders to someone enriching the world. And this time, the change was his choice. He is included in High Flyers 50, the fifty most eminent people of Indian origin living and working outside India.

I am proud to be an Overseas Indian—I am in fact an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) and it is always a joy for me to visit my motherland.

My family was impacted by Partition in 1947 when we found ourselves on the wrong side of the border. I come from a Hindu family and the part my family were living in—Sindh—became part of Pakistan.

We Sindhis are born traders. I love to do business, especially import/export business. As I often say in Hindi — Eeder ka maal oodur aur oodur ka maal eeder. Goods are sent from here to there and from over there to here—and on both transactions we make margins and profits!

In fact, on my first visit to India I heard this rather disturbing anecdote “that if you see a Sindhi or a poisonous snake don’t even think about who to knock out first!” My friends shared this with me in humour but I realise the negative perceptions that underlie such anecdotes and felt it was unfair given the amount my family has contributed to India and wherever in the world we have settled.

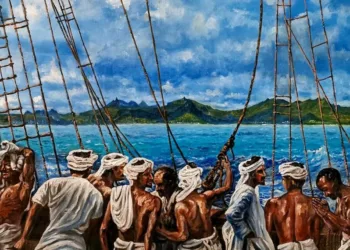

My grandfather and his brothers set up a business trading in silk between Japan and Africa. We saw an opportunity to sell silk saris to the Indian indentured railway workers and were sure the railway workers would use their hard earned money to buy these silk saris for their wives.

What is amazing is that in Sindh in British India, we were funeral singers and the lowest of the low castes. Yet my grandfather and his brothers were able to come out of relative poverty and made their fortune from this silk trade. My family set up an import and export business supplying silk from Japan to the ports of East and South Africa.

We generated enough wealth to build a palace—Moti Mahal—in Hyderabad, Sindh, British India.

I marvel at what it must have taken for my family to achieve what they did. No internet, no easy telephone service, just telegrams and letters sent by sea mail and then airmail. If my family could build their Silk Road when facing so much disadvantage then surely it has to be possible today to help the poorest of the poor to overcome poverty and build their own silk road.

The question is HOW do you do that when you have lost everything?

Our family had to flee from what was to become Pakistan during Partition, losing everything in Sindh. We managed to get on a ship just a couple of weeks before Partition and made our way to Mombasa in Kenya where my grandfather’s brothers continued in business.

We were in Kenya for 20 years and sadly once again were expelled with just 24 hours’ notice in 1966. I still remember the day when I found out the shocking news that my family had been given 24 hours’ notice to leave Mombasa.

Where would we go? Where would we stay? We were living in a 15-bedroom flat in the centre of Mombasa, with domestic helpers, cooks, cars and drivers. I was at a good school and doing well. What would happen to my education now and how would I handle the emotions of losing all my friends? Not to mention the daily swim at the local beach. Having lost everything again and arriving as refugees in London, we started life in a corner shop. Fifteen of us had to make do with four bedrooms and just one joint toilet and bathroom.

In tragic circumstances I lost my father in Kenya when I was just six weeks old and then my uncle when I was 17 years old. This is the cost and tragedy of partition and expulsions that so few people see or acknowledge in public.

My four brothers and I now had the enormous task and responsibility of seeking to not only survive but to build our own silk road following in the footsteps of our parents and grandparents.

Some of the lessons I learned on this journey on My Silk Road included learning how to live frugally. It is called very poshly— ‘deferred gratification’. What it meant for me was—very few immediate treats. Thank God I was not a smoker and I had to develop strong self-will to resist eating the chocolates in the shop I was helping run.

My brothers and I worked hard and were constantly on the lookout for opportunities to do more business. It’s called market research but really all I did was look and listen. I talked with our customers and learned that they were keen for us to be open outside the normal hours of 7.00 am to 5 pm. So my brothers and I decided to open the shop at 4.00 am to home-deliver newspapers to local customers for an extra fee. One evening after 9 pm we saw crowds of people coming out of a building and learned that they had spent their evening playing Bingo in the local Bingo hall. So we opened our shop for longer hours in the evening and were packed from 9 pm to 10 pm. So the same business asset—our local

corner shop—was now being worked harder and generating more cash and profit.

With my Open Ears and Eyes I heard and saw customers with a different accent and learned that they too were immigrants! Their accent was Irish. They were from Ireland! Their needs were simple. They told us that “We miss our local Irish newspapers and the chocolates and cigarettes that are sold in Ireland.” So we imported these goods for them and made even greater margins and the cash was flowing so fast that within two years we had six shops, each run by a different brother—although I was given charge of the finances. This involved not just cash flow management but also becoming an expert in dealing with hoondees—Bills of Exchange to raise working capital for a fast growing business. Banks were not willing to lend money to newly arrived refugees so hoondees were used by us to work with other newly arrived immigrants who had also started businesses—some having more cash than they needed immediately and others like us—needing more working capital. I often

had to ask family connections overseas for finance and this involved using the famous hawala system of international funds transfer. Without these desi financial instruments we would never have been able to generate the working capital and investment funds to run our businesses. So even though no banks were willing to lend us money given our lack of a track record in the UK we were able to draw on our international network of connections developed over years from the time of my grandfather and his brothers. The result was that we not only survived but thrived and succeeded beyond our imagination.

When I got married, my wife’s uncle invited me to work for his business—the Inlaks Group of companies and it was here that I was able to use my trading and financing skills with great ease and rapidly earn a promotion to become the Group Commercial Director, helping run a business that by the 1980s had several thousand employees, operating in 15 countries and turning over just under US$200 million per annum.

Those were heady days but one key lesson I learned during my time helping run the corner shop was the importance of getting a good education. Speaking with customers who clearly appeared to be professional and educated, I could see they were well-paid and worked limited hours. I learned a lot by reading stories in the newspapers and watching television programs that covered people of achievement and heard success stories on the radio. The common link in all these stories was—they were educated with professional qualifications and degrees. I am not saying this is essential because there are many who have succeeded despite having no formal education. But I could see the common thread of the significant part played by education.

I was also constantly reminded by my mother of how she watched her older sister Hari studying hard day and night and how Aunty Hari got a scholarship from Sindh to ultimately study for a PhD from the US. This was in the India of the 1930s! She set up the very successful Tagore International School in Delhi that today is run by her son Deepak and his wife Madhu. They now run not one but two schools!

So I decided consciously to follow my maasi, Aunty Hari’s example.

She became my role model. Here is another key point I learned. The importance of Role Models.

I myself had a battle to fight against the odds to get a scholarship to do my bachelor’s and postgraduate degrees. Of course my maasi’s challenges were more intense. A woman in the 1930s and 1940s travelling by ship to California on her own— wow, that must have been quite something.

I decided to follow her example and the rest, as they say, is history. A story that I have documented in my memoirs: “MY SILK ROAD: The Adventures and Struggles of a British Asian Refugee.”