Non-white communities in London have become more vulnerable during the pandemic because of their low economic and social status

By Deepak Pant

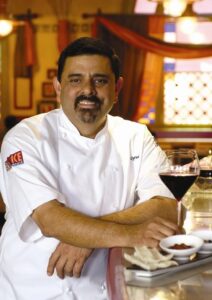

Sunil Kumar is a senior chef who migrated to London from New Delhi in 1999, going on to work in and then create several popular food joints in London over the years. He is cautiously optimistic. Many Indian restaurants closed during 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, when business dropped and owners laid off chefs and workers. “Business has slightly improved in the past six months but it is nowhere near what it was,” he says. “Things will get worse from September, when the government’s furlough scheme ends. How will the restaurants afford to keep the already reduced staff, then? People are still wary of going to restaurants, for good reason. We are hoping the government will relax its rules on 19 July.” Kumar is based currently at the Delhi Darbaar restaurant in Harrow.

He is not alone. Many owners of small businesses in the 15 lakh-strong Indian community are anxious about the future. The Boris Johnson government is due to announce a new set of rules on 19 July, with several norms likely to be relaxed, including the requirement of face-masks and social distancing. The overall situation in the United Kingdom has improved, mainly due to the success of the mass vaccination drive. Disapora Indians have been among the worst hit by the pandemic. In England alone, hospitals have recorded the deaths of 2,262 COVID-19 patients categorised as ‘British Indian’.

The Indian restaurant sector was struggling even before the pandemic due to several reasons, including tough visa rules preventing the recruitment of chefs from the Indian subcontinent.

The community has the highest death rate among all non-white communities, reflecting the fact that many work in public-facing services and industries such as health and transport. But a positive aspect is that vaccine hesitancy is among the lowest in the Indian community, unlike in other sections of the non-white population. Several religious places have been turned into community vaccination centres.

Most corner shops across Britain are historically owned by Indian migrants, with family members working in them over generations. Many have long-established relationships with local customers, as do Indian restaurant owners, who switched to offering takeaways to their loyal clientele. Both kinds of business have, largely, survived the pandemic. In central London and elsewhere, however, despite government support, many Indian restaurants have closed. They were unable to continue paying rent and meeting other expenses. Says Anuj Chande of London-based consultants Grant Thornton: “Such establishments do form an important part of the UK’s hospitality industry and while takeaway restaurants have probably benefited from the lockdown, eat-in restaurants have suffered and will struggle to recover once the government’s support measures are lifted.”

The Indian restaurant sector was struggling even before the pandemic, for several reasons including tough visa rules preventing the recruitment of chefs from the Indian sub-continent. The pandemic dealt a hard blow. Many restaurants have closed, but industry experts believe that even though the sector will recover only around 2024, the larger story of Indian food and its enduring appeal will retain its salience, with aficionados finding new ways to enjoy the cuisine.

In Southall, the complex matrix of job cuts, restrictions on movement, school and workplace closures have led to an increase in domestic violence, among other issues.

One of the casualties has been Indian Accent, an upmarket restaurant in central London that closed permanently. It has branches in New Delhi and New York but said in its closing statement: “This difficult decision was made as a last resort after carefully considering all the factors in play as a direct result of COVID-19. Social distancing would reduce the restaurant capacity to just 30 covers. This combined with the significant fixed costs as a result of operating on one of the most expensive streets in the world and the general economic uncertainty in the UK, means that the business is unviable at its current location.”

Says celebrity chef Cyrus Todiwala, who has been a leading figure in the sector since the mid-1990s, “Delivery companies were already putting restaurants out of business. This pandemic has driven a stake through our hearts. How can you sustain a business if only 20 or 30 people are allowed in a restaurant? People are scared to go to restaurants. We are all worried about the future of the industry. No one knows how the future will shape up, with a major fall in tourists and people working from home.”

The virus has taken individuals from across the community. For instance, Rajesh Jayaseelan, 45, who moved to the UK from Bengaluru a decade ago and made a living in London as a taxi driver. Several respected doctors working for the National Health Service have been lost, too. After all, doctors from India are the second largest group in the NHS, after UK-trained professionals. The grim list of doctors categorised as ‘Indian’ in COVID-19 death records include Jitendra Kumar Rathod, Krishan Arora, Rajesh Kalraiya, Pooja Sharma, Jayesh Patel, Vivek Sharma, Kamlesh Kumar Masson, Amarante Dias, Sophie Fagan, Hamza Pacheeri and Amrik Bamotra.

Among the casualties was one of India’s pioneering women editors, Gulshan Ewing, former editor of Eve’s Weekly and Star & Style, who set benchmarks in film journalism and focused on women readers since the mid-1960s.

But Asian casualties in the medical profession tell just part of the story. BAME (black, Asian, minorities, ethnic) communities constitute 13 percent of the UK population but are disproportionately represented among the COVID-19 dead, as well as among those admitted in intensive care units and in the numbers of new cases. Several studies by government departments, think tanks and charity organisations have highlighted the pandemic’s high impact on non-white communities. The underlying causes of the toll among BAME people include socio-economic status, cultural practices, and environmental conditions (largely influenced by structural biases based on ethnicity), all of which drive systemic inequality; the high prevalence of co-morbidities such as diabetes; as well as wider social and structural disparities such as racism, deprivation, living conditions and nature of employment.

The community has the highest death rate among all non-white groups, reflecting the fact that many work in public-facing services and industries, such as health and transport.

The challenge of dealing with the virus in non-white communities includes the larger incidence of multi-generation households compared to the white community. The impact has been felt at various levels due to restrictions, including financial pressures (owed to job losses), the inability to attend family events such as funerals and marriages, mental health issues arising from prolonged isolation, and an increase in domestic violence. London-based wedding planner Saheli Mirpuri says the industry has been severely hit, with tens of thousands of weddings cancelled. Some studies also suggest that in the early stages of the pandemic key public messages (for example, “Stay home. Protect the NHS. Save lives.”) did not reach sections of the non-white communities who are not familiar with the English language.

In Southall, the complex matrix of job cuts, restrictions on movement, school and workplace closures have led to an increase in domestic violence, among other issues. Says Virendra Sharma, senior Labour MP from Ealing Southall, “In London, the number of COVID-19 cases has been the highest in Ealing Southall, but now the people understand the importance of following official guidance. There has been an increase in mental health issues, also domestic violence. For example, earlier, a typical family’s day would be the husband and wife going for work in the morning, kids in schools, and all returning home in the afternoon or evening. Their interaction was less; now they are together 24 hours at home, which leads to friction. This is not the situation in every household in my constituency, but in many of them. The stress level is high, also because houses are small and the numbers living in them are high. Mosques, temples, gurdwaras have cooperated and remained mostly closed, but there is a section of the population that believes that if you don’t go to pray, your god will be unhappy with you, which can pose another challenge in these difficult times.”

The situation is not too different in the east Midlands city of Leicester, which has the unfortunate distinction of being the British city that has endured COVID-19 curbs for the longest period. It has witnessed waves of migration over the decades, including in the early 1970s people with origins in the Indian sub-continent who were expelled from Idi Amin’s Uganda. The migration has since rejuvenated the local economy — the arterial Belgrave Road is also known as Little India — and the city is now held up as a symbol of the success of Britain’s policies of multiculturalism, but it continues to face challenges that the pandemic has highlighted. There have been reports of workers infected with the virus not reporting it for fear of losing work and wages, while cases continued to rise in the city faster than elsewhere, until recently.

Trisha Hazarika, the Leicester-based sister-in-law of the Indian cultural icon Bhupen Hazarika, says, “Most people in our communities live in extended families, with elderly parents who are more vulnerable to the virus. Cases have been going up in areas such as Highfields and in lanes around Belgrave Road. There are also those who break rules. The police are now strict and fine people found organising parties. Many doctors who had retired came out and volunteered to help in hospitals, but contracted the virus and died after a few months. Those in lower-paid jobs in the NHS did not get personal protective equipment [PPE] in the early stages but were reluctant to complain for fear of losing their jobs if they did.” Her husband Prabin Hazarika, younger brother of Bhupen, has hardly stepped out of the home for months, following advice to ‘shield’. The couple has had limited contact with their own children, grandchildren and relatives.

(The author is a London-based journalist.)