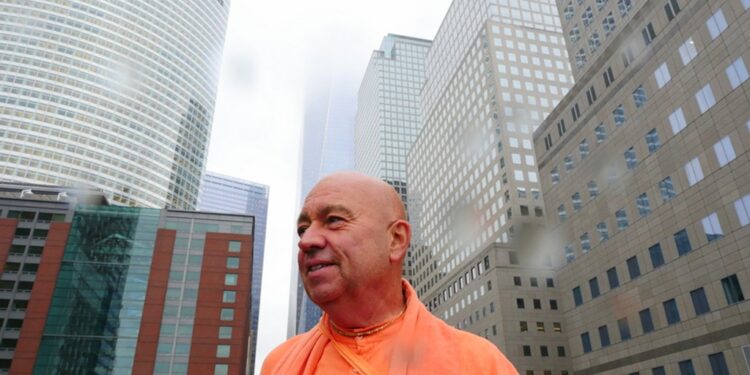

The young man who took to Krishna Consciousness and vegetarianism when he was 20 in 1973 never looked back. DIVYA KAELEY speaks to Bhaktimarga Swami on his journey of marathon walking and praying.

“So, here I was a pilgrim, a Caucasian in Indian orange garb, going through the rhythm of the day, taking in the good, the bad, and the ugly. But in truth, it’s all good.”

– Bhaktimarga Swami in The Saffron Path

Bhaktimarga Swami, born as John Vis in Chatham, Ontario, Canada, is also known as The Walking Monk for having trekked four times across Canada. He also crossed the US, Israel, Ireland, Guyana, Trinidad, Mauritius, and the Fiji islands and believes in the idea of pilgrimage. A documentation of his Canadian walks is found in two films: The Longest Road by the National Film Board of Canada, and Walking: The Lessons of the Road by Michael Oesch. He is also an instructor of Bhakti Yoga, a frontrunner in musical mantra meditation called kirtan, and a speaker on the science of the self, based on the teachings of the Bhagvad Gita. He pursues monastic ways, but maintains his artistic outlet through morality theatre as a playwright and director. This gives him an opportunity to work with the young in various communities.

The Walking Monk first took to the road as a marathon walker in 1996 to honour the centennial year of his guru, Srila Prabhupada, the Founder Acharya of ISKCON, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.

In “I don’t like cars”, the second chapter of his recent publication, The Saffron Path, the monk explains that his personal disconnect with the automobile began back when he was celebrating “those single digit birthdays”. He shares no romance with what he calls “the machines of madness”. “I was five when I made more serious and solo walking excursions to school and back home each day. No bus, no car, no regrets,” he mentions. “I don’t like cars, and when given the choice, I prefer to walk,” he adds.

As a youth, Bhaktimarga was a student of fine arts, but took to the life of a Hare Krishna monk at age 20 in 1973.He recollects the North America of the 1960s and ’70s. The presentation of India during those times was that people were poor, they worshipped cows and there was a dysfunctional caste system in the country.

The presentation was backward, even though there was a caste system in Europe as well and more corrupt. He says his interest was aroused by what “he didn’t hear”, with the absence of information and that’s what intrigued him.

He mentions Chaitanya as an interesting figure of the 15th century, who would travel on foot to various places in a state of absolute bliss chanting the Hare Krishna Mahamantra. Bhaktimarga says that as children they learnt about the British and Canadian traditions in history books, but nothing about Indian history. “Images of snake charmers and cows eating all the food” were more prominent and stereotypical.

Born in a white community in southern Ontario, and raised in an area where a lot of immigrants settled, Bhaktimarga was always fascinated by black Africans. “The first brown person that I met was my math teacher—Mr Budhram from Trinidad.” He goes on to say that “Indians are mild mannered people”.

Another big influence was a movie that Bhaktimarga watched during his young days, Nine Hours to Rama, that first exposed him to Indian culture. The film is a fictional narrative set in the nine hours in the life of Nathuram Godse leading up to his assassination of Gandhi.

At this time, there were also a lot of celebrities from Hollywood going to India to be with yogis. Especially the Beatles. When they returned from India, they started wearing Indian clothes and growing their hair longer, says Bhaktimarga. George Harrison took lessons in the sitar and took to chanting Hare Krishna. Harrison was, perhaps, the most unusual Beatle in his religious beliefs. Even before the Beatles went to India in 1968, he was captivated by Indian philosophy, culture and religion.

Bhaktimarga recalls meeting five Hare Krishna monks at that time and being influenced by their views on vegetarianism, reincarnation and chanting during a brief overnight stay at his apartment. At age 20, when he arrived at the ISKCON temple in Toronto, he sensed a past life connection and already felt like a Brahmachari. In 1973, he made a decision to bid farewell to his academic life for one of renunciation. As a child, he was raised on a farm, but could never understand how farm animals could become dinner. After meeting the Hare Krishna monks, he adopted vegetarianism, a tradition deeply embedded in India.

“When I told my parents that I was going to move into an exotic religious movement which had roots in India, they didn’t take it too well,” he says. There was one year left for his fine arts degree. “But they let me do what I wanted to do, as long as I wasn’t doing anything destructive. They were loving parents.” He told them he would have a simple life of discipline and they got used to the monk that he is.

After becoming a monk, Bhaktimarga embraced his new way of life. He joined ISKCON in Toronto. He discovered numerous ravines for their greenness and walkability. “In India people have been doing this for centuries,” he says, as pilgrimage is part of Indian spirituality. He recalls, in The Saffron Path, how in 1996, while doing rigorous walking, he spent eight hours a day chanting on the japa mala (chanting beads). “This ongoing process of repetitious utterance of the sacred sound offered solace to my mind.”

Bhaktimarga chose praying and walking as his wealth. At this time, he did observe a lot of his contemporaries having failed marriages and getting into drugs.“ Do introspective walking. People are overly materialistic and self-centred these days. Spirituality is on the backburner. We are not just made of fire, earth and water—we are much more than that. We are not this body, we are spirit (Atman).”

The Saffron Path is about the journeying in Canada and abroad. Bhaktimarga says today it’s important for young children to have exposure to spirituality and Indian traditions. This is possible if our culture is presented with an attractive western and “cool” twist. “Our teenagers can be role models for the younger ones and Sunday schools play a crucial role here.” Perhaps, if we present it in a fun way, they are going to like the culture, like mantra chanting with drums and harmonium. If you don’t do that, kids will go to rock concerts or resort to Bollywood; these may conflict with family values. “Give them a culture, not in a forceful way but in a loving way,” he smiles.

Apart from being an instructor in bhakti yoga, mantra meditation, kirtan, and interactive dance, Swami Bhaktimarga is also known for his passion for the performing arts. He has taken an active role in writing and directing morality theatrical productions that are presented all over the world. Some of his productions include The Jagannatha Story, Demon, Dhruva, Three Lives of Bharat, Ramayana, and Krishna the Eighth Boy.

Bhaktimarga Swami, now 70, has walked across Canada from coast to coast multiple times. He aims at the spiritual healing of the country. As he relives the emotional moments with his father—when he visited him during his final days—he recalls him telling the nurses: “That’s my son. He has walked across Canada several times. He is the strongest man in the world.” For what the monk does, the words certainly hold true.