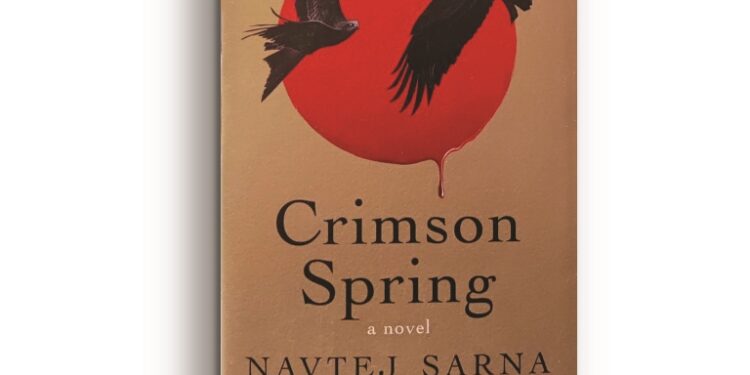

Navtej Sarna brings out the angst and poignancy of the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy, refracted through the lives of simple people

BY PARSA VENKATESHWAR RAO JR

While reading this novel, you must remove the historical and literary scaffolding that author Navtej Sarna sets up. The historical scaffolding is about the dates, the terrain of Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar, the chronology of events from the days leading to the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, and what followed, and winding its way to the hanging of Udham Singh in 1940 after he killed Michael O’Dwyer, who was the lieutenant governor of Punjab. There is also a need to ignore the explanations the author provides through many interviews. The literary scaffolding lies in the gallery of characters he sets up, some of them fictional, some real, through whom he tells the story. It is an artifice, an interesting one. Something that a good writer like Sarna does not hesitate to place up front. But the reader can do without them and plunge directly into the story.

The story of Maya Dei and Joga Singh is at the heart of the book, and how these two are caught in the political storm of 1919 Punjab. Maya is the simple rural woman of Punjab, she has her feelings and she has her values. Her faith provides the ballast. She walks through life’s vicissitudes with integrity. Joga is a man who chooses to lead the quiet life despite his education and his prospects in urban Rawalpindi. He keeps to his books and to the plain rhythm of an idyllic rural haunt with its fresh mountain streams and open fields. Maya and Joga are the quiet people who enjoy the blessings of life without being too self-conscious about the felicity of the life they chose without deliberation.

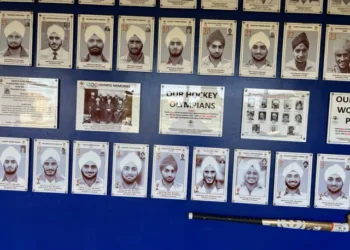

The Jallianwala Bagh explosion takes place and Maya and Joga are caught in it. Sarna describes the aftermath of the explosion with Homeric simplicity: “The sun went down in an ocean of blood and the night that enveloped Jallianwala Bagh was death itself, visiting each shadow, teasing out and trapping each escaping life.” And Maya’s traumatic moment is narrated in these short sentences: “Nobody else in the world knew that Joga Singh was dead, shot neatly through the forehead on Baisakhi day. Only she could do what needed to be done. She tried not to think of anything else.” The tragedy of Jallianwala Bagh is embodied in the lives of Maya and Joga. The other tender stories briefly narrated are of Mehtab Singh and Jindi, and of Hugh Porter and Milly.

The other characters—Ralla, Kirpal—are lovable, lonely individuals. Ralla finds his inner strength in the faith provided by his spiritual mentor. Kirpal, despite his exposure to the big, wide world and its momentous war, sinks into existential desolation, but he overcomes it and readies to join the fight against the brutal coloniser—joining the movement for the reform of gurudwaras. But Sarna captures the temporary moment of desolation powerfully: “All that he had been doing with pride now seemed so useless, futile. The uniform, the rank, the glory of battle was a sham, a huge deception.”

What makes this book an absorbing read is that it is written with a novelist’s circumspection for language, which is witty and arresting. Sarna describes the small gesture of Punjab Chief Secretary Porter to correct the wireless message he has dictated: “…he read carefully through the draft wireless message he had dictated, a blue pencil poised in his hand for corrections like a harpoon looking for a fish under the water’s surface.”

The Ghadar strand of the story is perhaps the most neglected part of the Punjab of those days. Sarna tries to weave it into the main story as it were. It can even be said that the Ghadar story is the main strand. But somewhere it remains unassimilated. We do not get a picture of Ghadar people, but only their mission to drive out the British. It is told through Sucha’s awakening, the orphan who reaches Tibba, the fictional village with its akhara, the wrestling pit, and the theka, the drinking den, and is taken care of by Bhima. The Ghadar folk remain hazy. Umrao Singh. Baba Wasakha Singh. The Ghadar movement must have fired the imagination of the patriotic people then.

But what hangs heavy in the book is Sarna’s earnest attempt to get the sense of Jallianwala Bagh and the Punjab of the times right and that is why he includes the Udham Singh story. And the restrained language falters when he writes the Udham Singh diary: “I have become immortal. I have become Bhagat Singh.” Something as bad as Thomas Hardy’s last lines in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, as pointed out by R.G. Collingwood!