BY RUKMA SALUJA

Designers from the Northeast have slowly acquired a footprint in fashion among discerning clients who understand heritage

Sustainable fashion is not merely a buzzword for designers from the Northeast who have made giant strides in integrating local aesthetics into mainstream fashion. No, this is not a new idea. It’s been around for a while. The fuel that drives these designers is the love for textiles, colour, design and fashion, it’s the endless patience, and commitment to preserving culture and heritage and the burning desire to give back to society that inspires some of our designers who have done remarkable work despite the many handicaps they had to deal with. For many of them, sustainable means supporting the local weavers.

“Sustainable fashion is also slow fashion,” says menswear designer Jenjum Gadi (label: Jenjum), based in Delhi with his roots in Arunachal Pradesh. “It is for those who understand and appreciate heritage and culture.” There’s a society called Exotic Echo Society in Dimapur to protect old practices. They grow and spin cotton, even dye it. “When I was asked to work on local fabrics and visited the weavers for the first time, I realised the richness of what we had and was determined to preserve the old techniques and heritage.”

This is laudable, considering production from the loin looms is painstakingly slow, sometimes as little as two metres of fabric a day. This is obviously not compatible with large collections, mass production, and the quick capsules that fast fashion demands. “This hit me but also opened a door as I began to think seriously about what I could do. It was an eye opener to see how some people are trying to protect an ancient practice in this way even though they are not designers.” He pauses and reflects, “This should be our collective responsibility, if you think about it. We are the ones who know clothes, design them, wear them.”

Charlee Mathlena, who works from Aizawl, doesn’t use mill- made fabric for his label, Heritage Mizoram by Charlee Mathlena. Together with the weavers and artisans he creates the fabrics he then uses for his designs. “It is slow,” he says. “One piece may take three weeks or a month and you have to wait for the fabric to come from the looms.” This obviously precludes following the common practice of making multiple collections in a year.

Stories on food and fashion tend to be on new talent and the latest openings and launches. We were able to speak to a few designers (we weren’t able to speak with many others), the front runners who struggled for years to put fashion from their respective states on the map, paving the way for younger talent. In most cases, it was ‘Lakme Fashion Week’ that gave them a platform over the years to showcase NE fashion or sustainable fashion. Winning titles in those early days gave them the fillip to dedicate their lives to a cause. “My father and grandfather are very well known in Meghalaya for doing social work,” says Daniel Syiem, co-founder and partner, Daniel Syiem’s Ethnic Fashion House. “I found that I could also give back to society and promote our culture and traditions through fashion.” He has adopted a number of villages in Meghalaya, helped set up looms and provides training, which has sometimes birthed new entrepreneurs.

Pollution levels in fashion are notoriously high as everyone knows. Slow fashion, according to Mathlena, sustains the artisans who make the fabric and contribute towards the industry, who do not pollute too much but are sustained by what they do. This in turn is sustained by certain people who like handwoven fabrics and handmade clothes. “Sustainable fashion is sustained by loyal clients who want your collection season after season, although we don’t do collections for every season,” he says.

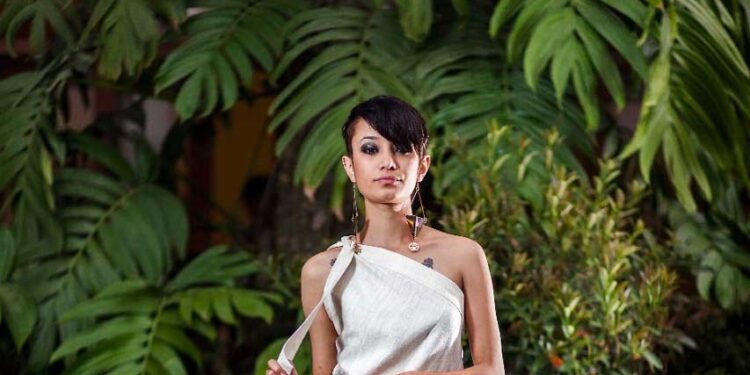

Syiem concurs. “I have a niche market. My clients understand what I do and value it. I work mostly with Ryndia, a local silk which is very expensive.” His silhouettes are inspired by the traditional jainsem and jenkasha worn by the women in Meghalaya. He turns these into contemporary glamorous drapes.

Syiem uses only vegetable dyes. These don’t allow for sharp colours but he’s okay with that. “That’s the USP of the brand. That’s what makes Ryndia so unique. It has an unfinished rough texture but the fabric is soft and smooth on the skin. The colours, I agree, are not too bright; they are dull earthy tones, which I love. These properties of Ryndia differentiate it from other fabrics.”

Mathlena, too, doesn’t strictly follow colour forecasts from the fashion world in the West. He makes his own colour scheme keeping in mind trends in Europe, but doesn’t always follow the au courant international colour palette. “I use a lot of black and white, which is always popular, and a lot of pastels and neutral tones. Softer colours work better nowadays.”

The way they incorporate local sensibilities to mainstream fashion varies. For Mathlena, it’s important to be genuine and true to his local roots and sensibility. He takes Mizo weaves to the national and international space. “One needs to understand tribal culture to be authentic,” he says. “I take up local crafts and bring them to mainstream markets by joining slow fashion or sustainable fashion. This has a niche market.” He uses traditional motifs keeping them classic or giving them a new spin. The fabrics are the same but the motifs are different. The designs are woven into the fabrics. Weavers in villages neighbouring Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, weave his designs. “When you put traditional motifs, they work the best. It’s amazing that even people who do not understand Mizo culture will be attracted to traditional motifs and weaves.”

Syiem too works with the weavers but tends to take inspiration from the clothes worn by the women in Meghalaya. His silhouettes are influenced by the jainsem and jenkasha, the traditional attire of the women in Meghalaya. These he transforms into elegant and contemporary designs.

Gadi finds it difficult to pinpoint this or that motif and its significance. While Arunachal has many tribes, he is from the Galo. “We celebrate Mopin, a harvest festival in spring during which we wear white, the colour of our tribe. It denotes purity and productivity, spring, new life. The patterns are not so important. It is the colours that are more important.” Different colours indicate different tribes. In his recent line he’s mixed

Mughal and Rajasthani patterns with tribal motifs from Arunachal. “Maybe in time this mixing of our local and indigenous designs with those from other states will become my signature style,” he says. “Perhaps that’s the way to commercialise and popularise NE designs. These haven’t been explored and used, so there’s something new.”

Waste fabric left over from cutting garments is used in accessories by all of them, or as detailing on cushion covers and runners. Gadi even makes standalone pieces from waste fabric. These are one-of-a-kind and tend to fly off the shelves.

@daniel_syiem @DanielSyiem’sEthnicfashionhouse @charleemathlena @jenjumgadi1 @jenjumgadi @rukssaluja