With films from the south reaping big commercial success as well as critical acclaim, Hindi cinema needs to break free from the beaten track and reliance on overpriced fading stars

BY SAIBAL CHATTERJEE

Indian cinema is in the middle of a major churn. Like any major churn, this one is exciting and full of possibilities. But as with all things exciting, the seismic shift is also riddled with uncertainties.The ground beneath the feet of our filmmakers, especially those in Mumbai, has been swaying one way and then the other, leaving the industry in a state of confusion.

Take the case of Kantara, a lively drama rooted in the folkloric traditions of coastal Karnataka. It tells the story of one pugnacious man’s fight to protect the physical and spiritual core of the forest that is home to him and his people. Coming from nowhere, the film has turned out to be one of the biggest hits of 2022.

That isn’t the end of the Kantara phenomenon. In the span of a few months, Rishab Shetty’s film has gone from being one of the best reviewed releases of 2022 to popping up on yearend lists (albeit only a few) of the most overrated Indian films of the year. But that is the nature of the beast. The rough and the smooth are two sides of the same coin.

THE FESTIVAL CIRCUIT

At the recent 27th International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), two new Malayalam films—Lijo Jose Pellissery’s Nanpakal Nerathu Mayakkam (Like An Afternoon Dream), starring Mammootty, and Sanal Kumar Sasidharan’s Vazhakk (The Quarrel), with Tovino Thomas and Kani Kusrutt in lead roles—received an overwhelming response from delegates.

At every screening of these two films, there were probably more people outside the hall than inside it. Does this groundswell indicate that Nanpakal Nerathu Mayakkam and Vazhakk will be money-spinners when they play in the theatres sometime in the near future?

Filmmaker Ranjith Sankar, director of Njan Marykutty, Sunny and 4 Years, isn’t so sure. “I wonder if people will be queuing up quite like this when these films are released theatrically,” he says in an informal conversation. Sankar was on the committee that selected films for the IFFK’s Malayalam Cinema Today section.

Indian cinema is definitely changing its contours and dimensions as Mumbai movies spearheaded by Bollywood’s male megastars bite the dust with alarming regularity. The script is perforce being rewritten as much by the filmmakers themselves as by the audiences they cater to.

It is no longer good enough for a movie to stick to the tried and tested. Taking risks is the name of the game. Kantara threw caution to the wind and went out on a limb into uncharted territory. It has as a result soared to heights that medium-budget, starless films rarely do.

The sleeper hit was initially released in a limited number of theatres. Word of mouth on social media triggered a giant buzz. As a result, Shetty and his team had to add screens and release dubbed versions of the film for audiences nationwide.

BREAKING BOUNDARIES

“No language is regional anymore,” says Shetty. “The talk of pan-Indian films is, to my mind, misplaced. Every film today has the potential to break geographical boundaries, not just within the country but also across the world.” That is exactly what Kantara has achieved.

“The more regional you are the more universal you are likely to be. Hyper-local themes are the way forward for cinema,” says Shetty. Interestingly, Shetty, besides his acting and directing duties, has produced festival favourites such as Natesh Hegde’s Pedro and Jaishankar Aryar’s Shivamma, winner of the New Currents Award at the 27th Busan International Film Festival.

Shetty is also bankrolling Hegde’s sophomore venture Vagachipani (Tiger’s Pond), which will be filmed in and around the part of the Western Ghats in Karnataka where Pedro was shot. Hegde continues to live and work in his native village.

“Kannada indie films have of late been making a mark in film festivals,” says Hegde. “Unfortunately, that isn’t translating into good OTT or theatrical distribution. I strongly believe that the acceptance of indie films in their own states will result in many more such films.”

Hegde is of the opinion that the success of KGF and Kantara will lead to more big-budget extravaganzas in the Kannada movie industry. “If producers are sensible enough, they will realise the importance of a varied approach, which, thankfully, a few of them are already working towards,” he adds. However, he is worried that as a consequence of the monster hits that the south industries are delivering, independent films will be increasingly sidelined.

SUPERSTARS CHANGE TRACKS

Rishab Shetty is one of the few who straddle the distance between commercially-oriented cinema and arthouse films. His approach is indicative of another change that is sweeping through cinema in south India. The line between the two kinds of moviemaking is being blurred by adventurous producers and directors, something that Bollywood has thus far been unable to see value in.

Take the example of actor and producer Fahadh Faasil. The Malayalam movie superstar constantly experiments with his roles and films, employing his popularity to boost the profile of unusual projects that require a hand up. In doing so, he has created a niche for himself and the kind of cinema he champions as a producer. Mahesh Narayanan’s C U Soon, made during the pandemic, and two other Fahadh Faasil starrers that landed on Amazon Prime Video in 2020-21—Dileesh Pothan’s Joji and Mahesh Narayanan’s Malik have bolstered his nationwide fan following.

In 2019, Faasil produced and acted in Madhu C. Narayanan’s Kumbalangi Nights, which was among the films that started a phase that saw him push in new directions. There are no lead actors in the Mumbai industry who possess the vision of a Fahadh Faasil or a Dhanush, one of Tamil cinema’s most bankable stars who moves freely between commerce and social relevance. That probably is one of Hindi cinema’s biggest problems.

BOLLYWOOD MALADIES

Amit Khanna, veteran film producer, screenwriter, lyricist, author and media columnist, blames the Bollywood star system for the way things have panned out in recent years. “Filmmakers in Mumbai,” he says, “did not lag behind in reinventing themselves, but the reinvention was subverted by the huge stardom of the actors.”

Khanna points out that before Laal Singh Chaddha, six to seven of Aamir Khan’s releases had scriptwriters of proven quality. Laal Singh Chaddha is Aamir’s first film without a professional writer. “He took too much upon himself. His stardom led him to believe that he could be everything,” he adds.

Overreach, Khanna fears, could be the undoing of Pathaan as well. He asks: “What business does Shahrukh Khan have to become an action star? I am not saying Pathaan might not become a big hit, but he has played a romantic hero all his life.” The shift, says Khanna, does not stand to logic. “Who are you trying to satisfy, not your loyal fan base for sure?”

Conversely, one cannot keep doing the same thing again and again, he says. Khanna, who began his career with Navketan Films in the early 1970s, adds: “We saw it with Devsaab, too. He had the most loyal fans. However, after the 1980s, though the fan base survived, he kept making bad films. When you do that, the fans might continue to love and admire you but they will stop queuing up for movie tickets.”

Therein lies the rub. “Stars tend to mistake crowds for ticket buyers. Burnouts are inevitable in stardom,” says Khanna, who is currently writing a book, Alchemy of Fame, which looks at how movie actors can lose the adulation of the public when they stop playing their cards right.

SOUTHERN FRESHNESS

On why films from the south are doing infinitely better than those from Mumbai, Khanna says: “In spite of the universality of their films, there is a fundamental freshness in how the South Indian directors treat their subjects. Plus, they have a new set of actors who have the wherewithal to carry a film on their shoulders.”

Khanna adds: “That (the rise and rise of the southern stars) has changed the competition base. Now suddenly there is a level playing field and you are not competing anymore with 10 people but with 20 or 30.” Bollywood stars trapped in old habits are inevitably going to struggle in the new scenario, he feels.

An overconfident Mumbai movie industry had expected fans to rush back to the multiplexes once the pandemic ended. Hordes of them did return for the theatrical experience but they did so more for movies from the south. Big-budget Bollywood films fell by the wayside. The industry was plunged into disarray.

ALERT AUDIENCE

Witness what transpired after the October release of the Adipurush teaser. Based on the Ramayana and starring Prabhas and Saif Ali Khan as Rama and Ravana, respectively, the mythological extravaganza, reportedly the most expensive ever made in India, promised jawdropping visual effects. What it proffered in the teaser was tacky computer generated imagery. Viewers gave vent to their disappointment on social media.

Alarmed at the flak that the teaser drew, Adipurush director Om Raut decided to postpone the release of the film by over five months—from January 12 to June 16. A salvage operation is currently on. Raut has admitted as much.

He declared on Twitter: “Adipurush is not a film but a representation of our devotion to Prabhu Shri Ram and a commitment towards our sanskriti (heritage) and history. In order to give a complete visual experience to the viewers, we need to give more time to the teams working on the film.”

The move demonstrates two key changes in the Hindi movie industry. One, the audience now has ways to express itself aggressively for better or for worse even before the release of a film, which, in turn, has led to a boycott culture. And two, filmmakers can no longer be secure in the belief that the presence of A-listers in the cast will guarantee a bumper opening.

One of the reasons why Hindi cinema has lost some of its lustre is the steady dilution of its primary purpose—entertainment. It now panders to the whims of overpriced stars and, worse, bends over backwards to serve up expedient propaganda.

CINEMATIC PIZZAZZ

At the other end of the spectrum, consider two recent Tamil films— Karnan, directed by Mari Selvaraj and starring Dhanush, and Jai Bhim, helmed by T.J. Gnanavel and fronted by Suriya. These films dived into the real struggles of marginalised communities to tell gripping stories of exploitation and resilience with remarkable cinematic pizzazz. Especially striking were the visual flourishes of Karnan, a film rich in metaphoric cross-references.

Karnan and Jai Bhim were 2021 releases that in significant ways redefined the parameters of commercial cinema. Pa. Ranjith, maker of Kaala, Kabali and Sarpatta Parambarai, says: “It is not easy to consistently articulate a specific social consciousness in mainstream cinema. But mainstream cinema, thanks to its reach and appeal, is the best vehicle that there can be for spotlighting stories of communities that have faced exploitation and marginalisation for centuries.”

The focus has understandably moved appreciably. On the global stage, Indian documentary makers continued to strike gold. The year 2022 began with Writing With Fire, directed by Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas, earning an Academy Award nomination in the Best Documentary Feature category.

In early 2022, Delhi-based filmmaker Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes won the Grand Jury Prize in the World Cinema Documentary competition of the Sundance Film Festival. In May, the film took home the Cannes Film Festival’s Golden Eye Prize for the best documentary.

Pan Nalin’s Gujarati-language Chhello Show (Last Film Show), an ode to cinema of the pre-digital era, has deservedly been picked as India’s official submission for the best international feature Oscar. Its tale of a village boy discovering the magic of cinema is a work that appeals to both the heart and mind.

Shimla-based filmmaker Siddharth Chauhan’s Amar Colony has bagged a Special Jury Prize at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. The young writer-director ended the year with another triumph at the IFFK—the Federation of Film Societies of India’s K.R. Mohanan Award for the best debut director.

INDIE FILMS SCORE

So independent Indian cinema, as distinct from the star-driven films that Mumbai produces, did enough in 2022 to keep the flag flying. Chauhan and his ilk embody the new spirit of adventure in the choices that he has made as a filmmaker.

“Himachal Pradesh has no filmmaking infrastructure,” he says. “But I have a small group of friends whose support I bank on to keep making films out of Shimla.” Chauhan cut his teeth on several critically acclaimed short films before beginning work on his feature-length debut, Amar Colony.

When Adipurush hits the screen in mid-2023, it might prove the detractors wrong, but the storm that it has run into and the filmmaker’s response to the hubbub bear testimony to the uneasy relationship between the industry and the constituency that keeps it alive.

Consider the fate that befell Samrat Prithviraj and Ram Setu, both starring Akshay Kumar. They arrived in the multiplexes amid great fanfare but did not create so much as a ripple. The makers of the two films learnt the hard way that it is far easier to play fast and loose with history and peddle pulpy myths than to get audiences to buy into unabashed claptrap, especially when it is aggravated by incompetence.

Akshay Kumar, who delivered other resounding duds in 2022 (Bachchan Pandey, Raksha Bandhan) was by no means the only A-list Mumbai movie star who suffered such massive debacles. Ranbir Kapoor’s Shamshera sank without a trace, Ranveer Singh’s Jayeshbhai Jordaar was a non-starter, Ajay Devgn’s Runway 34 hit turbulence and nosedived and Aamir Khan’s Laal Singh Chaddha found the going tough.

The massive vacuum created by the underperformance of the Bollywood biggies was exploited to the hilt by blockbusters from down South—Pushpa (released in December 2021), RRR, KGF 2 and Kantara. These pan-Indian hits changed the rules of the game. Bollywood suddenly realised that hyper-local themes were the order of the day.

Says Khanna: “This was coming. The newer set of directors in filmmaking centres other than Mumbai is now much better-equipped. Many of them are film school grads. Many no longer have the parochial approach that was the case 25 years ago and earlier. With their modern, global sensibilities, their creative and production practices are of the highest order.”

GLOCAL CINEMA

The change is yielding dividends and the four south Indian cinemas are no longer content to serve audiences in their own respective languages. In the past, the likes of Rajinikanth and Kamal Haasan were names to reckon with across the nation but when they needed to reach out to an audience outside their immediate sphere of influence, they had to do Hindi-language films. Today’s south Indian stars can work in their own language and still connect with audiences all over India.

“With the advent of multiplexes, there is a need to constantly feed the 4,500-plus screens across India. These screens can facilitate a pan-Indian release irrespective of language,” says Khanna.

Not that the aforementioned south Indian films, barring the Kannada-language Kantara, had any intrinsic merit beyond their surface gloss, star power and technical razzmatazz. One might argue that the Telugu-language RRR is all the rage in the West today and that its maker, S.S. Rajamouli, has been adjudged best director of 2022 by the New York Film Critics Circle and has also bagged a Golden Globe nomination. Truth be told, it is a manipulative, cheesy, crass Indian potboiler, only flashier and louder than any Hindi movie of a similar timbre has ever been.

PULP FICTION

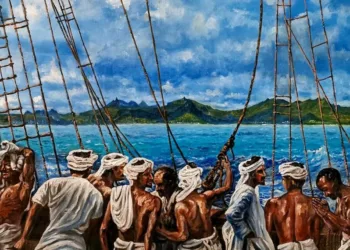

In RRR, history is a big casualty. The epic scale of the movie is impressive, no doubt, but it expends an inordinate amount of energy on the trivialisation of the under documented history of tribal resistance against the British Raj and other forces of exploitation about one hundred years ago.

The nuances of the battles that marginalised communities wage or any meaningful detailing of time, place and character are beyond the ken of RRR. So, what was it about the movie that made the very elements that undermined the likes of Samrat Prithviraj and Ram Setu the reason for its enviable commercial success? Hard to put a finger on it.

In mythologising the real struggles of real personages, RRR appropriates the struggle of forest dwellers and tribals and uses it as a mere pretext for an SFX-laden, power-packed cinematic blitzkrieg that obviates all possibility of a genuinely empathetic account of the rebellion of oppressed people.

Nagraj Manjule’s Jhund, with Amitabh Bachchan and a host of amateur actors, played a very different game. Unsurprisingly, the three-hour film failed at the box-office, but it showed exactly how the theme of caste and class oppression can be handled without turning it into a pretext for stuffy spectacle.

Jhund is a story of the walls that the socially marginalised run into, and are thwarted by, at every turn. It does away with two mythologies that form the foundation of mass entertainment in this country: one springs from the Hindu epics, the other from the dominant idioms of Indian popular cinema.

With both given a wide berth, what emerges in Jhund is a structure and a style that are embedded in the very nature of the struggle that the dispossessed are engaged in on a daily basis merely to keep their heads above water.

Jhund puts one of the biggest stars of Hindi commercial cinema front and centre and, drawing upon true events, constructs a narrative that captures a motley group of marginalised youth who, through a mix of good fortune, bold assertion and daring action, seek to break free from the life of petty crime, drug addiction and privation that they are condemned to due to social ostracism, poverty and lack of education.

Big-budget Bollywood is paying a high price for underestimating an audience that has evolved since the coronavirus outbreak thanks to its exposure via the streaming services to cinema of all kinds and from diverse geographies.

Be that as it may, it isn’t all doom and gloom for Bollywood. It did have a few success stories in the year gone by. Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2, a horror comedy, and Brahmastra Part One: Shiva, a superhero fantasy that enabled Ranbir Kapoor to live down the abominable Shamshera, found takers at the box-office.

DETHRONING MASCULINITY

Brahmastra, which kicked off Bollywood’s first-ever proposed superhero trilogy, has dashes of originality to go with its sweep, scale and style. That is not to say that it is perfect. Parts of it are rudimentary, others could have done with some pruning. Overall, Brahmastra tweaks the conventions of the superhero movie somewhat. As a result, it isn’t slavishly derivative.

For one, Brahmastra abjures the kind of hypermasculinity that films of this nature usually perpetuate. The screenplay does not celebrate unbridled machismo.The male protagonist willingly acknowledges the centrality of the woman in his life, played by Alia Bhatt.

Bhatt spearheaded another of the year’s better commercial movies, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Gangubai Kathiawadi. Women of the world’s oldest profession plying their trade and fighting for justice in Bombay’s Kamathipura in the Nehruvian era are at the heart of the film.

Factual accuracy isn’t the period drama’s strong suit. But Bhansali, aided by a gifted female lead, squeezes every ounce of dramatic effect out of the script. The result is an immersive film that does not feel overly stretched even though it runs a little over two and a half hours. Meant to be a satire on patriarchy, Jayeshbhai Jordaar is one of many recent Yash Raj Films (YRF) releases that failed to connect with the masses. Samrat Prithviraj, also a YRF production, is, expectedly, a purveyor of fanciful history draped in the glossiest of Bollywood finery. It is colourful, action-packed and laced with music but spectacularly soulless.

Another YRF dud, Shamshera was an excruciatingly bad action flick. Set in the second half of the 19th century, an era in which the heroine is allowed to be draped in new millennium fabrics, it throws a bundle of things into a cauldron that turns everything to ash and dust.

Laal Singh Chaddha, a reworking of the 1994 Hollywood hit Forrest Gump, wasn’t half as bad. The principal strength of Laal Singh Chaddha stemmed from its stress on the power of hope in a time of violence and venality. Unity in diversity isn’t a particularly original idea, but its reiteration, no matter in what form, had never been more necessary. Unlike Laal Singh Chaddha, Aanand L. Rai’s Raksha Bandhan, a film without any redeeming features, is set in contemporary times. But it could be mistaken for a 1950s film, given the shockingly regressive ideas it embraces.

Raksha Bandhan would have us believe that girls are worth nothing if they are not married and domesticated. Headlined by Akshay Kumar (Bollywood’s poster boy of all things sanskari) who plays big brother to four girls incapable of finding their way in the world.

Raksha Bandhan, Shamshera, Ram Setu and the rest sum up the redundancy of Bollywood’s old ways. It was hard to believe that anybody would make a film such as these in 2022. The girls of Raksha Bandhan, like the film and the industry, were caught in a time warp.

MANI RATNAM’S MAGIC

One of the high points of the past year was Ponniyin Selvan – Part 1. Shrinking a complex five-volume novel into a two-part movie was no mean feat. Mani Ratnam pulled it off in style. The sprawling, spectacularly mounted film is an ambitious, near-flawless adaptation of a much-loved work of Tamil literature.

Needless to say, the tale makes huge technical and artistic demands on Ratnam and his cast and crew. They prove equal to the onerous task of attaining the magnitude, the pacing and the stylistic flourishes that the story demands and available image-making technology allows.

Ratnam does not resort to sensory or visceral overdrive, drawing strength instead from the smart script written by him, B. Jeyamohan and Elango Kumaravel and from a cast of actors at the top of their game. PS-1 is a treat for the eyes as much as it is for the mind.

History and mythology coalesce purposelessly in Ram Setu, a cinematic abomination of epic proportions. The film occasionally cites books and other sources of knowledge to draw a convenient conclusion about the Ramayana, Lord Rama and Ram Setu that smacks of brazen mendacity.

Parts of Ram Setu, based on a story by creative producer Chandraprakash Dwivedi (who helmed Samrat Prithviraj, which was designed to feed into a largely similar narrative) pretend to be science fiction.

NEW STUFF

Two inventive Mumbai movies that have made amends to a certain extent for all the low-grade stuff that Bollywood foisted upon its fans were Amar Kaushik’s Bhediya and Anirudh Iyer’s An Action Hero. The former, filmed entirely in Arunachal Pradesh, subverted the bodyhorror genre to craft a tale about the man-animal conflict and the need to protect indigenous cultures and reverse the denudation of forests.

The latter tapped into the conventions of a revenge tale to construct a lively and entertaining commentary on notions of heroism, the nature of movie stardom, the scourge of media overreach and distortions of reality in a world where truth is invariably buried under an avalanche of noise, images and hysteria.

In the guise of a thriller, An Action Hero held up a meta-mirror to Mumbai movies and the masses that consume them. The relationship between the two has been fraught, of late. Repeated box-office failures have compelled complacent film producers to shed dead habit and return to the drawing board.

As filmmakers from the south make dramatic inroads into the pan- Indian market and some of them also earn critical hosannas in the bargain, Hindi cinema can ill afford to rest on its oars and let fading superstars keep holding it to ransom. It desperately needs to break free from its methods of yore and seek fresh avenues that lead into the future. If not exactly a now or never situation, it is a call to action that Bollywood can ignore only at its own peril.

(The writer is a reputed film critic and columnist.)