Budget 2023-24 might have no major changes but a clutch of tweaks gives the Indian diaspora reason enough to continue investing back home

BY KUMUD DAS

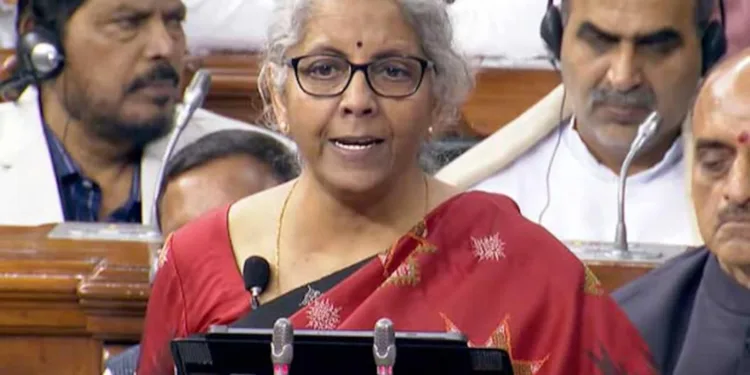

Despite there being no major announcement in this year’s Budget which was presented by Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in Parliament on February 1, it still brought smiles to the faces of 3.2 crore-odd members of the Indian diaspora. The reason is simple: A host of tweaks that could impact the way NRIs invest or earn from their Indian assets.

For instance, in a move to sync Indian foreign exchange regulations with the Income Tax Act, the Budget proposes to bring issuance of shares to non-residents above the fair market value within the tax purview. This will prevent generation and circulation of unaccounted for money from

non-resident investors in a closely held company in excess of its fair market value. Of course, this is just the tip of a large iceberg in terms of sops gifted to the Indian diaspora.

“True, there is no change in the tax slabs as was applicable for Non-Residential External (NRE) clients or other non-resident Indian clients. But they have also included the category of resident but not ordinary residents in this category, where gifting done by an NROR or non-resident ordinary resident to a resident Indian would be taxed in India going forward. Interestingly, there are a host of such sops in the proposed Budget,” says Anand Khanvilkar, product lead–Strategic Alliances, IIFL Securities.

India has caught the fancy of NRIs for the past few years. This is evident from the fact that in terms of overall remittances, India received more than $100 billion in the last financial year. On an average, remittances are growing at an annual rate of 5-6 percent. It has gone up to more than 12 percent over the last financial year, largely due to contributions by a substantial section of the diaspora, says Khanvilkar.

More than 65 percent of the Indian diaspora in the top 14 countries are today remitting large amounts of money to India. While 60 percent of such remittances go to investment in various kinds of savings in India, the balance goes into different asset classes.

According to Khanvilkar, “The fact of the matter is that the rupee has been depreciating at the rate of 3-4 percent per annum on an average for the past few years. Last year alone, it depreciated more than 10 percent, which provides an opportunity to migrant Indians to park their hard-earned money back in the country of their origin. In fact, it is also a reason behind the sudden surge of remittances happening across India.”

Coming to the various categories of migrant Indians, there are two major types: Overseas Citizens of India (OCIs) and Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs). OCIs, particularly those living in Gulf countries, who can’t have a permanent residence in those countries, prefer to live post-retirement in India.

Of course, the major component of this money is going into bank deposits today, typically in terms of NRE and NRO FCNR deposits held with public and private banks.

So, from a Budget perspective, why the government has not made any changes is because the remittances have been substantial as domestic growth is very strong in India in multiple sectors and profitability across corporates is good. There has also been transparency and ease of access to banks and capital markets, with a dedicated scheme of NRI segments catering to the requirements. The currency interest rate arbitrage and return arbitrage is the most critical thing to consider, as compared to what the NRI customers are getting in their in-country investment opportunities. The larger portion is typically in banks where larger amounts of deposits are held tax-free. So, from the point of view of the Budget, there was nothing in terms of investment to be sought or a certain kind of investment to be discounted for taxes.

As for the interest rate scenario prevailing back home, it has reduced drastically to 4-5 percent now from 12-13 percent until 2006-07.

NRI customers are taxed at the same rate applicable for

domestic customers. So there has been no per se change in terms of taxation from an NRI perspective because short-term and long-term capital gain taxes were applicable earlier as well. So primarily there has been no change in terms of assessing the fair market value. They can always take the fair market value in terms of the indexation benefit which they get and also the grandfathering clause, which they can apply, where they can also look at the current market price or the market price applicable as per the grandfathering clause.

From a short-term and long-term perspective, the tax rates have remained unchanged for quite some time. The short-term capital gains tax is 15 percent which comes to post-cess around 17.94 percent; long-term is around 10 percent which would be around 11.96 percent which remains the way it was. They have been paying taxes and banks have been deducting taxes at source on any kind of equity market or debt market transactions that the customers are doing today. Similarly, they are applicable for even PIS investments. Things have changed in terms of debt mutual funds from a short-term perspective. The effective taxes have come down slightly by around 2-2.5 percent to around 39 percent. From

an equity mutual fund perspective, in the short term, the implications are the same.

They will have to pay around 39 percent of tax for short-term purposes. The same element will be applicable for AIS as well. There will be a benefit for the client in terms of whether the client has a tax residency certificate (TRC) for availing of the double taxation avoidance agreement between the two countries. If they are able to provide a TRC, they will get benefit in case of tax for income distribution on mutual funds.

(The writer is a Mumbai-based senior business journalist)