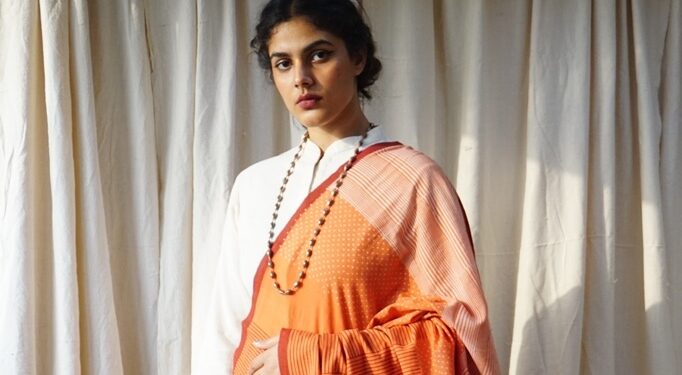

Khadi has a historical connotation but does it still resonate with the young Indian? We speak with experts to understand the best way forward to keep this beautiful fabric relevant

BY RUKMA SALUJA

Khadi, handspun cotton on the charkha and woven into fabric on traditional manual looms with slubs and irregularities firmly in place. Not

intentionally, but because of the handmade element and lack of technological expertise back in the 1920s when it became a rallying point and a part of the Swadeshi movement. That’s not to say it was a new idea at the time. Handspun and handwoven go further back in time to before the machines took over. Gandhi ji made it a movement of the people for the people to take a stand against the British predatory practice of buying low-cost raw material from India and selling finished fabric back to Indians at high profit margins. In later years, it lost sheen, becoming the fabric of choice for professors and nerdy intellectuals. Until designers like Rohit Bal, Ritu Beri and Ritu Kumar, Anju Modi, Rajesh Pratap Singh and others began to use it in their collections.

Fashion moves on in search of newer textiles and styles. Besides, globally, the industry has made enormous strides in sophisticated technology and production. Low-cost, breathable, comfortable and sustainable, khadi always made a lot of sense. In recent years, it has found easy and casual acceptance with style-conscious shoppers. Or has it?

Gandhi ji spinning yarn on the charkha is the abiding image we have of khadi. But the world has moved on since then and ‘that’ khadi has morphed into yarn spun on amber and New Model charkhas, updated versions of the old one or you could say a replica of a non-mechanised or a manual powerloom. A contradiction in terms but that’s what the upgraded version amounts to. Khitish Pandya of Eco Tasar with roots in Bihar, who manufactures handwoven fabric for export and large-scale orders for home furnishings, believes it is all a matter of economics. “It is not viable to continue with that old style of weaving. There’s the matter of quality and also of price. Obviously, mill-made fabric is going to be

cheaper and of better quality.”

The government of India understood this as far back as the Sixties and has made a push to subsidise it ever since. Pandya feels a better approach would be to support weavers and designers and allow it to become a niche artisanal product. “Handloom cannot meet the volumes the market demands,” he says. “It doesn’t make sense to have it compete with mill-made fabrics. This is the story even in technologically advanced countries. You still have artisans making handmade tapestries that sell at astronomical sums. We can accord our weavers and artisans the same respect.” The push given by the government can only go so far if we continue to expect it to be on a par with industrially-produced textiles. “The Ambanis may be able to buy it at exorbitant sums of money at an event, but how often will it be worn and how many

sales did that event or that gesture generate? What measly percentage of that money from that sale or that government push actually percolate down to the weaver? At best it’s a talking point. We want to keep alive the romance of khadi in the traditional sense.”

Sudha Dhingra, professor at NIFT, and director at the Centre of Excellence for Khadi (CoEK), a government-funded project, feels there is a huge difference in what khadi was, and what it is. “It is no longer that thick, unattractive, rough-looking fabric. It can be as fine and diaphanous as

muslin,” she says. “It is no longer coarse khaddar. There’s very fine cotton coming from West Bengal, and a fine silk called eri from Assam and the Northeast which is called ahimsa silk.” The cocoons are not boiled to take the worms out. A slit is made in the cocoon to let the worm slip away. “CoEK aims to build capacity and leverage the fabric to the high-end rather than the mass consumer,” she says.

The KVIC (Khadi & Village Industries Commission) started CoEK with the aim of diagnosing and correcting khadi’s problems and image. Part of the aim is to bring in a fresher and younger aesthetic to the finished garments. With Delhi as its headquarters, there are centres in Shillong,

Kolkata, Gandhinagar and Bengaluru. According to the website: “Khadi and Village Industries production is more than Rs. 27,000 Crore and providing employment opportunities to 1.34 Cr. persons.” That’s not surprising at all as apart from apparel, other items available include blankets, furnishings, stationery. Toiletries from brand Khadi are known to be made from largely natural, even vegan, formulations.

Khadi is sold at the Bhavans where the styling is old-fashioned and sloppy, where the bureaucrats running them are not aware of fashion. The same old kurta-pyjama sold for decades in the same old cuts holds little appeal for the fashion conscious shopper. Diksha Khanna (label:

Diksha Khanna) says, “Khadi products are ‘flawed’ and not mindless creations of machines. This versatility makes it an all-season fabric. At the same time, khadi should be made into products that are relevant in today’s fashion scenario. This needs a careful study of national and

international trends in colours, styles and silhouettes and their interpretation for Indian and international consumers. Also, the design explorations could be made classier, keeping in mind the key forecast trends and the target market.”

Dhingra has identified another bottleneck. Designers like Anavila Misra, Shani Himanshu, Rta Kapur Chishti, Anju Modi, and Rajesh Pratap Singh, who even makes a range using khadi denim, use it regularly but cannot call it khadi as that would require certification from KVIC,

which involves a rather confusing, cumbersome and protracted procedure. Without certification, they use the terms handspun and handwoven. There are other young designers who are keen to use it and to market it as khadi but when they can’t due to stringent government rules, the loss unfortunately is brand khadi’s. The ‘khadi numbers’ therefore tend to remain slow if not static. Also, the cap on the numbers or volumes sold through KVIC with the khadi brand is a deterrent.

Perhaps Pandya is right; perhaps the government should not try to make it a commercial success through volumes. Handloom with its meagre output from the looms cannot achieve the quantities woven by the mills. Let it be exclusive, he suggests, so that the money and the respect percolate to the weaver, the artisan.

@cvic @dikshakhanna