Extensive research undertaken to salvage the moribund language of the Great Andamanese community offers rare glimpses of the unknown world of the only-surviving pre-Neolithic tribe…

By Prof Anvita Abbi

“Hold on to your language, don’t let it slip away”

These were the words of Boa Sr, one of the last speakers of the Great Andamanese languages. Languages are the witness of the diverse and varying ways the human cognitive faculties perceive the world. Each language has unique lexical stock and unique signification. Various manifestations of language are ecological and archaeological signatures of the communities that maintain close ties to their environments. Languages carry evidence of earlier environment, habitat, practices, way of living, the worldview and secrets of survival which may or may not be in the memory of the community. Hence, language death signifies the closure of the link with its ancient heritage. When a language is on the verge of extinction a mammoth treasure dies along with the language. Its history, its culture, its ecological base, its knowledge of the biodiversity, its ethnolinguistic practices, and above all the identity of the community. Great Andamanese is such a language that is on the verge of extinction. With barely three speakers left who are more rememberers of the language than the speakers, we are on the threshold of losing one of the oldest civilizations and also perhaps the proof of the very first human language. The structures of the Great Andamanese language are unique and have no parallel with any language of the world known so far. The grammar of the language which was brought out in 2013 is proof thereof.

The history of the present critical situation of the Great Andamanese language is a saga of many tales that finally led to the almost moribund status of the language. The significance of the language can be ascertained by the fact that the latest research by geneticists indicates that Andamanese are the descendants of early Paleolithic colonisers of Southeast Asia and are the survivors of the first migration from Africa that took place 70,000 years before the present. Further studies made by the geneticists indicate that they lived in isolation all their lives till the British came to the island to make a penal colony in 1858. All these factors bring home the fact that the Great Andamanese and their languages have retained some of the archaic features in their language–untouched by any language contact. Great Andamanese is a general term used for ten different but mutually intelligible languages that were once spoken on the Great Andaman. The present Great Andamanese is a mixed language, a kind of a koiné drawing its lexicon from four different languages, viz. Jero, Bo, Khora and Sare but grammar is based on Jero. The current study was based on this koiné variety.

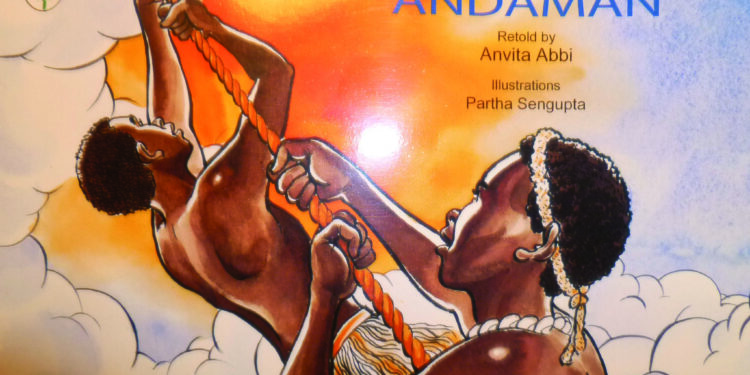

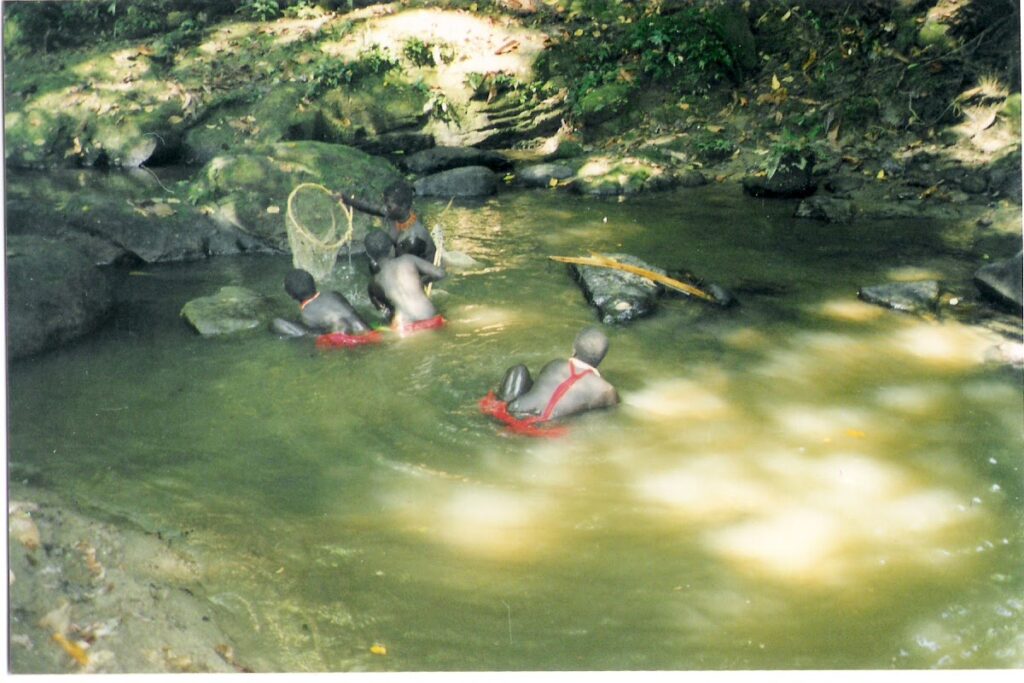

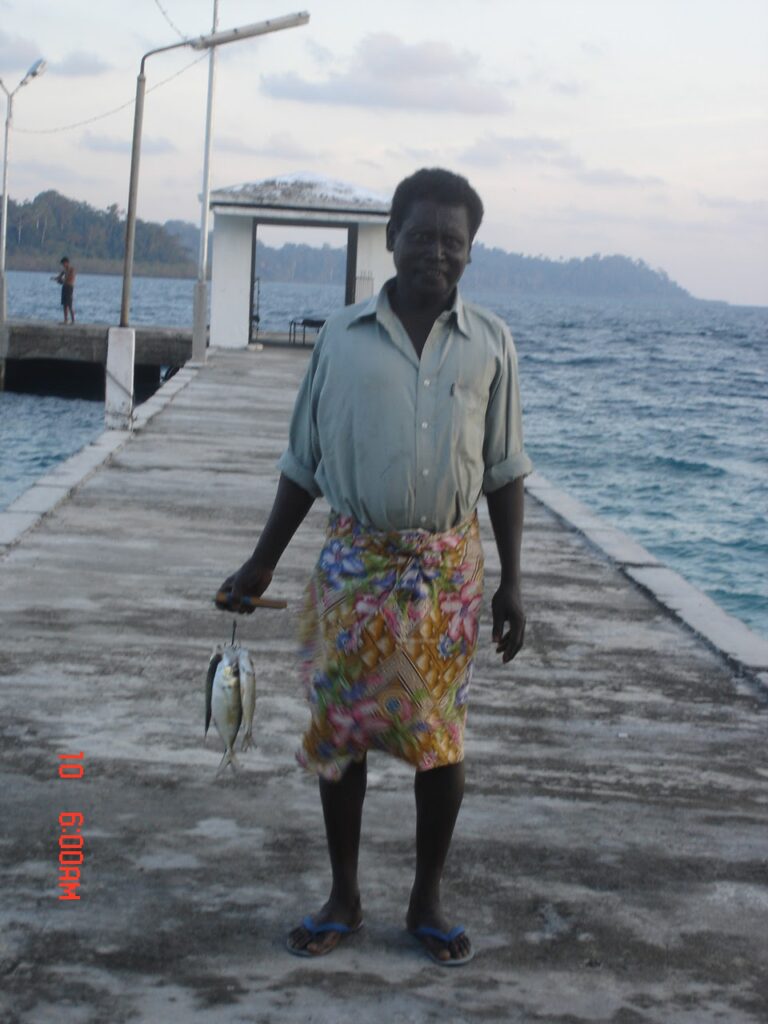

The members of the Great Andamanese community live in the city of Port Blair as well in jungles of Strait Island, 53 nautical miles away from the city of Port Blair. The Great Andamanese were hunters and gatherers till very late and some of them still prefer to hunt in the sea rather than accept free dole from the Government of India. The so-called “assimilationist policy” of the Indian government has rendered the tribe subservient to the local population and bureaucracy. My introduction to the community was made in late 2000 when I conducted a survey of the languages of the Andamans including those that were spoken by the three tribes viz. Great Andamanese, Onge, and Jarawa. My initial research indicated that Great Andamanese was very distinct from Jarawa and Onge (I call them Angan languages) and constitutes the sixth language family of India which was later corroborated by the population geneticists. Considering the language status as moribund, I geared myself to plunge into documenting their language and realised that the knowledge of the Great Andamanese people about forest, sea and the environment was captured in the language that exposed the ecological richness of the area. What followed was the encyclopaedic trilingual talking dictionary (see the cover page of the dictionary published in 2011). I was tempted to work with an ornithologist to map the Andamanese names of birds with their scientific names. We were amazed to find more than 40% parallels. This resulted in another book (see the cover of the birds book). While collecting data for the birds book I was told that although Great Andamanese are hunters, they neither hunt birds nor do they eat them as birds are considered their ancestors. This led me to explore their myths and soon I was absorbed in eliciting tales from the only living person who narrated ten stories with great difficulty as he or anybody else in the community had not heard any story in the last forty years. Two of the folk tales have already been translated into Hindi and the one on Phertajido is being translated into 12 Indian languages by the National Book Trust.

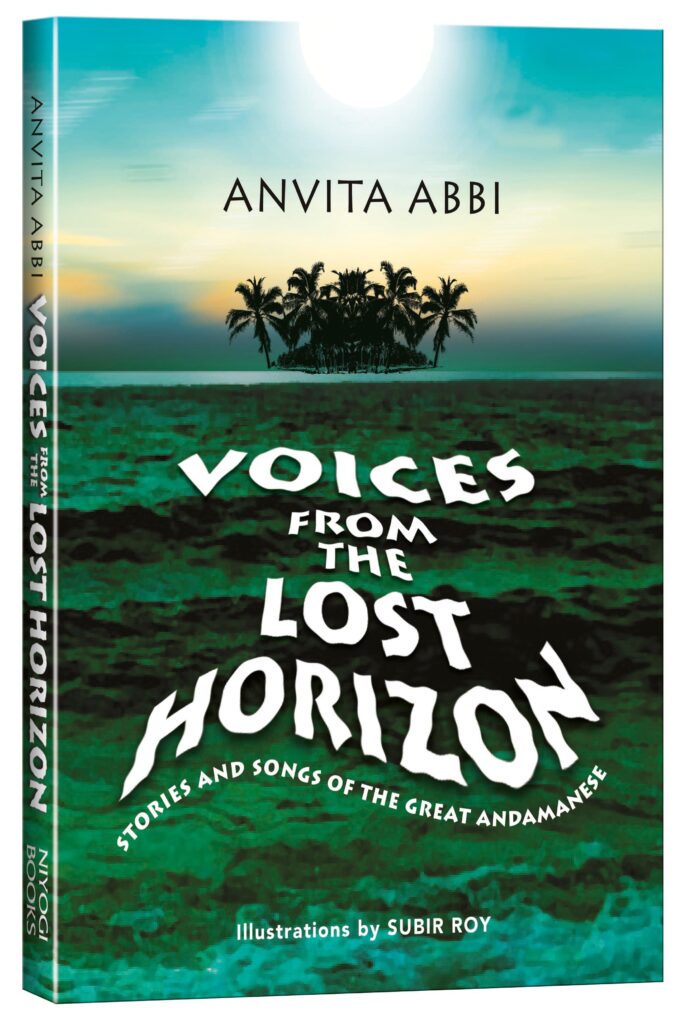

When a language dies the narrative power dies first. Another member of the tribe who spoke the Bo language sang several songs which were recorded in the tsunami relief camp in 2005 but it took me more than three years to translate them as the language had almost perished with only one speaker remaining in the community. These stories and songs are documented in my new book Voices from the Lost Horizon. It is a unique document as this is the very first and perhaps the very last (as singers and narrators are no longer on this earth) piece of the oral tradition of the Great Andamanese that has come to light. The book comes with the first-person narration of the process of elicitation of stories from a dying language and of course 10 valuable unique stories including creation tales as rendered to me by Nao Jr, the speaker of the Jero language who breathed his last in 2009. Each story is beautifully illustrated. There are 46 songs in the language with Romanisation followed by Devanagari script so that the Andamanese children can recite them and English translation. It carries a QR code that helps readers to log on to the video of songs rendered by Boa Sr. who left this world in 2010.

The present Great Andamanese is a mixed language, a kind of a koiné drawing its lexicon from four different languages, viz. Jero, Bo, Khora and Sare but grammar is based on Jero.

About The Author

Anvita Abbi, an eminent linguist and social scientist, has identified the sixth language family of India. A recipient of the Padma Shri and Kenneth Hale Award, she was a Guest Scientist at the Max Planck Institute, Leipzig, and Leverhulme Professor at the University of London. She has taught at the Jawaharlal Nehru University and in universities across Europe, Australia, Canada and the US. Renowned for her research on lesser-known languages extending from the Himalayas to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, she has numerous publications in the field and is now documenting endangered languages of the Nicobar Islands.

Fading Memories of the Great Andamanese

Excerpts from the book ‘Voices from the Lost Horizon. Stories and Songs from the Great Andamanese’ by Anvita Abbi

The Andamanese forgot their language, could not speak full sentences, and remembered only the words

“While each story or song in this collection carries extraordinary beauty, the ‘Great Narrative of Phertajido’ has resonant quality unlike any other. A short but complex narrative of ethnogenesis, the story is suffused with emotion and themes of survival. We are introduced to Phertajido, the first man of the Andaman Islands, who originated from the hollow of a bamboo stalk”.

Mart Turin

University of British Columbia, Vancouver

“On my first visit to the island, I was disappointed to see that most of the adults spoke in Andamanese Hindi. When I asked why they did not speak in their indigenous language, they admitted that they had forgotten it all. On pressing a little hard, I realised that they remembered the words, but perhaps not full sentences. I said, ‘Ok, you can teach me words,’ and thus started my journey of learning Great Andamanese. It also turned out to be a journey of language revival, as some elders started speaking among themselves to use it as a code language so that I don’t understand their communication. This was encouraging, as I came to know they still had competency in the language, but their situation did not allow them to practice it. I grabbed the opportunity and gradually convinced them to translate a few Hindi sentences in Great Andamanese.”

Anvita Abbi, p.34

From the story, I learned that there were four kinds of funerals in their society.

- When a person dies of a natural death or in illness s/he is buried in the earth (‘boa-phong’ meaning ‘hole in the earth’).

- When a person dies while hunting/killing, then s/he is put on a platform made on a tree (‘machaan’ in Hindi) and burnt.

- When a person dies because of choking on a fishbone, his body is taken to a particular place near Mayabandar in the northern part of the Andaman Islands and left for a month on a tree for vultures to eat. The bones are collected after a month.

- When children pass away, they are not buried initially; they are left untouched for a few days, then they are cremated.

Juro’s story raised mixed feelings of remorse and pity. Juro’s son loved his mother but could not bear her atrocious habits of headhunting and, thus, he became instrumental in her killing. Nao thought what he did was right and beneficial for the society. I was amazed at the way he compared Juro with the Hindu goddess, Kali, repeatedly. Although I found little similarity between the two, I didn’t contradict him.

p.55

The Tale of Maya Lephai

Lephai was a young man who loved a girl immensely. He wanted to marry her though his friends warned him that the girl was seen with another man and did not bear a good reputation. He did not believe his friends and said, ‘No, no, I am going to marry her,’ and he did so eventually. They had four children thereafter, two boys and two girls. One fine day, he went hunting in the jungle to catch some game for his children. Somehow, he got delayed in coming home. When he came back, he found his wife missing. When he looked inside the house, he found his children crying and there was no sign of their mother. He asked them,‘Why are you crying?’

p.63

Konjo song of the Jeru language

ṭuṭu li nukhu

thara chaṭo

ṭuṭu li nukhu

thara chaṭo

—Sung by Nao Jr (M 55)

Straightening small bamboos,

sweat drops fall.

Straightening small bamboos

Sweat drops fall.

p.119

A Bo Song

aan khile ṭhii maa

era chomer ṭu oroo

laa ee ḍaa gri laa roo

laa ee ḍaa gri laa roo

—Sung by Boa Sr (F 80)

Leaves, flowers, bees,

falling on the ground.

Cutting tree for a boat!

Cutting tree for a boat!

p.144

“The salvation work undertaken by Professor Abbi was far from easy, considering the practical problems of conducting linguistic fieldwork and compiling an audio-visual documentation in an environment with minimal infrastructure—only two hours of electricity daily—with the additional initial reluctance of the community members to open up their world to outsiders, who only too often are identified with the forces that have led to the loss of their culture and of their self-esteem.

It is fortunate that a scholar with Professor Abbi’s tenacity, as well as her scientific credentials, was available and willing to conduct this work. She has rendered the documentation of the language by recording stories and songs, and has also compiled a substantial grammar and dictionary of the language, the first truly modern linguistic studies of any of the indigenous languages of the Andaman Islands. This is truly ground-breaking work that has saved a language from oblivion”.

Bernard Comrie, Santa Barbara, California

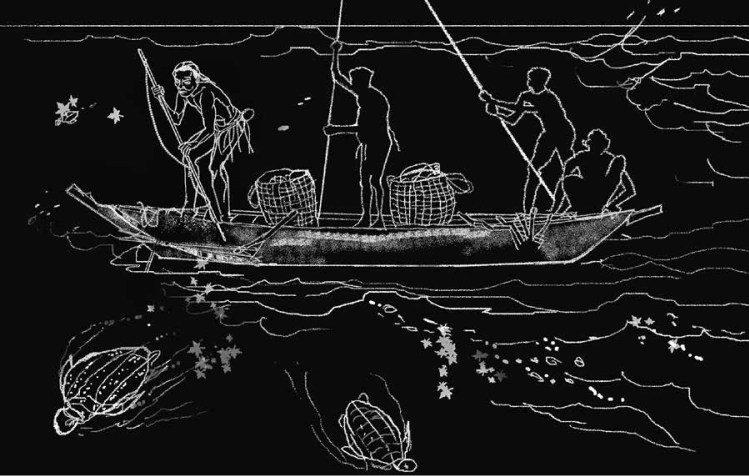

Illustration by Subir Roy p.100

Publisher’s Take

‘Language comes first, thoughts and imaginations follow.’ When I begin with this famous quote, I mean to say that a language not only chariots our thoughts but also it has the power to even mould our thoughts. Wittgenstein once famously said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” So, as the language gets limited, so does our cognitive ability. And when we lose a language, we lose all the ideas which are perhaps unique to the land as well as the people and culture. For example, the Great Andamanese language has 91 words for “birds” and 6 words for the “sea shore”! But, as the speakers of this language go obsolete, we lose a very important link of our humanity.

Hence, we at Niyogi Books, firmly believed that the book – “Voices from the Lost Horizon”, which tries to document some of the stories and songs from the Great Andamanese, both in the written words as well as in the audio-visual format, needs to be published. Dr Anvita Abbi is an authority in this subject and her extensive work is not limited to endangered languages but also the correspondingly endangered ecology. She also points out the interconnectedness of nature and languages while drawing attention to the devastating consequence of the loss of the language on humanity.

This book is also one of our first attempts to capture these endangered languages through stories, songs and other forms of literature keeping in mind for posterity. While the intellectual activities behind the making of this book are much more important than the final product, as a publisher, we thought the final product might make the readers think and make their languages more vibrant. I believe if we coalesce more often and bring out a significant body of such works, we can truly make a difference.

Trisha Niyogi,

COO & Director, Niyogi Books