The Olympics are dominated by the large and rich countries, while the small and poor lag behind.

Small economies have not yet created any stir in the Olympics, the exceptions being Kenya and Jamaica, which have specific strengths.The reason, of course, is they do not have the resources, infrastructure and, as smaller nations, have other more pressing concerns.

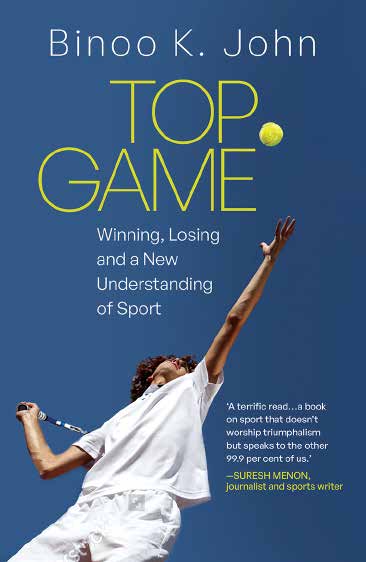

By Binoo K. John

Small countries that are developed also face the same problem. Singapore is an example—despite being an ideal state with an enviable record in nation building, the third-ranked nation in the world on per capita GDP, being a major global financial and service sector hub, with no apparent lack of facilities, Singapore has not made any headway in sport—that is, except for the achievement of Joseph Schooling who got a gold in the 100-metre butterfly race in Rio when he defeated his hero, Michael Phelps, no less. Singapore’s strengths are in table tennis and badminton, but an Olympic medal seems distant. The reason could be lack of national will and its comparatively low GDP of above $300 billion (compared to India’s over $2 trillion), ranking it thirty-sixth in the world, is another. There is no evidence of any specific traditional strengths, despite a huge percentage of the Chinese population, and no geographical advantage like say, Kenya’s Rift Valley. And of course, its frighteningly low population of just over 5 million (compared to Hong Kong’s 7 million) could be the main problem. One possible way for Singapore to emerge as a sporting nation is to invite medal-winning sportsmen from poorer countries to take up residence there like Qatar, for instance, is doing. Mind you, thirty-six migrants were among Britain’s Olympic medal-winners in London 2012! Evidence suggests that everything has to be huge for a country to become an Olympic power:economy, population, geographic size, infrastructure. This also shows that physical superiority is as much a rare phenomenon as intellectual superiority. Only the US, UK, Germany, France and China combine both.

Just as the rise of China as a sporting and economic power can be used to explain the link between wealth and sporting superiority, the economic decline of Japan during the last one decade and more can be used to further look at how national wealth reflects on its sporting ambition. Japan has been among the top ten or nearby since 1960. It came third in the Tokyo Olympics, 1964, with sixteen golds after being in the eighth rank in Rome, Italy, in 1960 (four golds,

eighteen total), demonstrating that Japan was rising up from the debris of the Second World War to assert itself as an economic and sporting power. In 1968, in Mexico, it came fifth with thirteen golds and retained the same position in 1976. In Sydney, 2000, it slumped to the fifteenth position with five golds and a total of eighteen. In 1996, in the Games held in Atlanta, Japan was beginning to go into a recession, which was a contributory factor for its lowest ranking in many years, when it won just three golds and a total of fourteen

Economists call the 1990s Japan’s ‘lost decade’ as recession (negative growth in three successive quarters by the textbook) set in. In the 1990s Japan’s GDP grew by only 1.5 per cent and this continued to the next decade in one of the most disastrous recessionary cycles happening to an advanced country. Japan was the second largest economy from the 1970s till the slump hit. In a way, China’s rise was inversely proportional to Japan’s slump. In the 1960s, Japan grew by 10 percent, 5 per cent in the 1970s and 4 per cent in the 1980s. In one quarter of 2009, Japan touched a record low of minus 4 per cent even as China

zoomed away. For some time in the decade starting 2000, Japan showed signs of coming out of recession, but again in 2014, there was a contraction.

More alarmingly, Japan’s birth rate has been falling for over a decade and its population is predicted to fall below 100 million by 2048. The country has lost 40 million people in the last fifty years. Japan’s trade war with South Korea and China has added to its problems with exports plummeting and debt spiralling out of control.

Individual brilliance can always rise above such economic hardships. The rise of Kei Nishikori as a tennis powerhouse is an instance. But games like tennis are insulated against problems of individual countries and Nishikori anyway trained and is based in the US, even though in the background there was a Japanese programme to spot geniuses in sport. Similar is the case with some Japanese athletes. But, overall, to think that Japan will emerge as a super Olympic power in the near future is open to question. The country bounced back to finish sixth with twelve gold medals in Rio, 2016, so maybe Japan has found ways of still funding sporting activity and the hosting of the 2020 Olympics.

‘Commentators have alluded to the link between economic and sporting superiority, but few have actually gone into the details of it because there is no final truth in this theory and there can always be exceptions’

Various commentators have alluded to the link between economic and sporting superiority, but few have actually gone into the details of it because there is no final truth in this theory and there can always be exceptions. But overall, there is surety about the link between economic superiority and sporting superiority, as I have shown here.

Fareed Zakaria, international affairs commentator, wrote in the Washington Post of August 2016, about the overriding superiority of

the US in the Olympics: ‘Then there is the US—decentralized, unplanned, chaotic, with a government everyone loves to hate. Yet it’s the undisputed champ. Why? Partly because US public policy actually works quite well and has encouraged excellence in many sports. Mostly it is the reflection of the American spirit which celebrates individualism, embraces diversity and relentlessly pushes for excellence. And that spirit is even more important than winning.’

Commenting on another pathetic show by India in 2016, Zakaria commented: ‘India’s underperformance might be one more reflection of an enduring feature of the Indian landscape: private excellence but public incompetence. Governance in India works very badly

Evidence suggests that everything has to be huge for a country to become an Olympic power: economy, population, geographic size, infrastructure.

‘But there is more to it than that. India does not bring the unified nationalist fervour that China brings to these global competitions. Perhaps because of India’s diversity, perhaps for other reasons, but it is difficult to imagine the country uniting as China did for the Beijing Olympics.

‘Poverty is the easy explanation. India is still a very poor country per capita. But India’s per capita GDP is what China’s was in 2000. That year China won 58 medals (with

28 golds) about 30 times as many as India won this summer.’

According to US government estimates, India will be the third largest economy by 2030, barring catastrophes. The Coronavirus pandemic is a global catastrophe and so

this projection is unlikely to come near fruition. In the case of India, no imagined catastrophe can be ruled out, but roughly the GDP in trillion dollars for the projected

top five for 2030 is as follows:

US : 23.9 I China 18.8 I India 7.3 I Japan 6.5 I Germany 4.3 I UK 3.8

This clearly shows that already developed nations may plateau out in sport, just as their economies may. This is also because the population of many such developed nations is too low to sustain any major level of growth, according to economists like Ruchir Sharma—he says that to sustain growth at present levels, Germany needs a million migrant population every year till 2030.

India thus does not fit into the economic might-to-medal theory. This is because the enviable growth of India is only about ten years old though the basis of it was laid in 1991, when the markets opened up and the economy was gradually reformed. Southeast Asian nations like South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia and even Taiwan showed how small is beautiful in economics. India had an average of 8 per cent growth for eight years and then around seven. If India sustains this growth for two decades, then the sporting scene will benefit enormously. India’s GDP calculation, however, has been disputed by some economists.

(Excerpt from Top Game: Winning and Losing and a New Understanding of Sport, Speaking Tiger, Price: Rs 499. Available around the globe on Kindle.)