EGIDIO MONIZ found his passion after his retirement in a country that is a haven for the brew that delights millions across the globe

BY ROWENA KAY MASCARENHAS

“Coffee is an art, more like a passion, akin to producing grapes for wine. It obliges you to become a better farmer,” says the ‘Indiano’ in Brazil, Egidio Moniz, founder of the coffee brand, Café Goa.

My generation cannot do without it. More than two billion ‘cups of joe’ are drunk every day, and for many it is virtually impossible to carry on a work day without it. The story of coffee drinking and growing worldwide is a deeply fascinating one linked to the history of the world and its wars and that of Sufi saint Baba Budan, credited with “smuggling” the first coffee beans into India in the 17th century. When I heard recently of the Brazilian coffee brand “Cafe Goa”, I caught up with its founder, to unravel what is the fascinating story of Egidio Moniz, and his efforts to maintain a connect with his ancestral homeland, Goa.

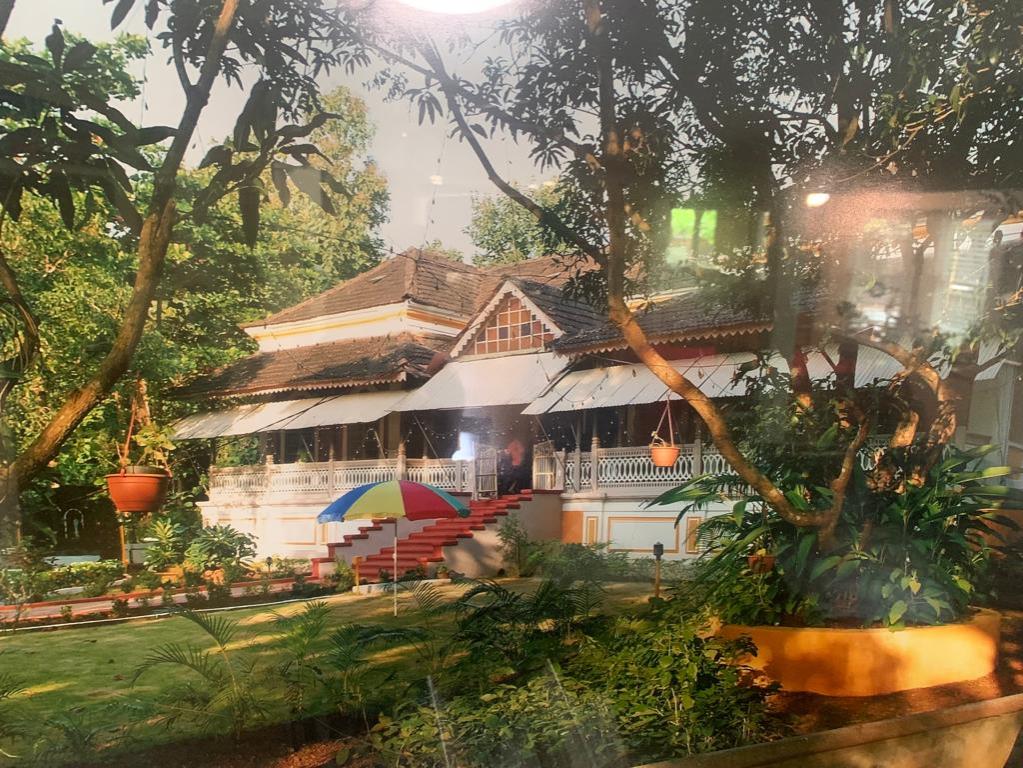

Moniz’s earliest memories relate to his grandmother’s resplendent home in Curtorim, Goa, which had a yard full of fruitbearing trees where they, as children, frolicked in the layers of hay that were used to ripen the mangoes harvested every summer. Etched in those memories are three striking coffee trees, and the process of plucking the coffee cherries when they changed from green to red. His grandmother dried, roasted, and ground the coffee cherries into coffee powder for home consumption. Always an abundance of produce off the land and fields, the home never saw any limitations on food. Little Egidio could have barely foreseen what life in Bombay would come to mean to him. As a child of nine in 1957, he accompanied his father to Bombay, an annual trip his father would make over the years to relocate each bus from the other side of the border all the

way to Bombay.”

Mazagaon, in Bombay, was where his father, Riario Moniz, had a three-room house and where Egidio would spend the next 12 years of his life with his father and siblings, while his mother, Helena Quadros, continued to look after familial responsibilities in Goa. The relocation took him from a life of abundance in Goa to a frugal one in the big city where rice, milk, sugar and flour were rationed. In Goa, the children would sink their teeth into 700 mangoes every season, but in Bombay they would get seven mangoes, one for each child. Yet, for Egidio and his siblings, the move to Bombay unlocked the best Jesuit education at St Mary’s School, a private Catholic secondary school for boys founded in 1864.

In 1969, Moniz moved to Pune to do his B.Sc. in agriculture. In 1973, he returned to Goa after completing the four-year undergraduate course and took up a job with the government as an agronomist. At the time, two significant events were unfolding in his life; both would shape his future in an immeasurable way. The first was his decision to apply for and acquire a Portuguese passport; it was to pave the path for his migration to the West. And the other was meeting his wife-to-be, Lourdes Lobo, at a family picnic in Colva. They would go on to marry in 1977, and raise two sons, Nilesh and Ravendra.

Moniz left Goa for Brazil in 1975, via France. His college senior, Gill Rebello from Divar, had moved to Brazil a few years earlier, and the experience was worthy enough for him to invite Moniz to join him there. After taking a temporary job, Moniz got his lucky break and was recruited by Imperial Chemical Industries (later acquired by AstraZeneca and Syngenta), where he went on to spend the next 36 years spanning sales, research, tech, and stewardship in sustainability. He moved seven times: Maringa in the state of Parana, Campo Mourao (also in Parana), Santo Angelo and Passo Fundo in Rio Grande de Sul, and three postings in the state of Sao Paulo, Ribeirao Preto, Campinas, finally closing a long and successful career in Sao Paulo city.

His career with ICI began with what would eventually be termed an exciting era in the “no-till movement” in Brazil. He was part of the team that worked on zero tillage, where soybean was planted through direct drilling. Yields began to double and farmers, though initially slow to catch on to technology, were sharp enough to understand that costs were less and erosion was under control. Today, it is fair to say that zero tillage has taken root in Brazil, with millions of hectares under cultivation.

However, it was Moniz’s stewardship project, School in the Field, that brought him accolades, and an award in 2008-09. Under this project, he modernised the process of training 25,000 to 30,000 school students every year, in rural areas, on the principles of Safety, Health, and Environment (SHE) in agriculture. He retired from Syngenta in 2010-11.

Moniz began to work on his 32 hectares of land at Araguari in western Minas Gerais at an altitude of 950 metres above sea level in the Cerrado biome whose weather characteristics make it easier to produce gourmet coffee. The Robusta coffee-bean trees in his grandmother’s house had a profound impact on him, as also the memories of jackfruit and cashew trees, every time he returned to visit his grandmother’s home. “I started with one worker, and gradually increased the workforce with an agronomist who would visit occasionally. Now, I have 4,000 Arabica plants per hectare, and a production capacity of 1,500 sacks of coffee per year,” says Moniz, beaming with pride.

There are two activities in the year that are significant for coffee plantation owners: harvesting and pruning. “Beginning in June and going on till the end of August, I stay at the farm for the harvesting and drying process. During this time, I employ locals to work on my farm, using machinery for harvesting and processing,” he says. Immediately after the harvest, the trees are pruned by his workers. Ninety percent of the coffee harvest is exported and 10 percent is sold locally. Sales are achieved through cooperatives as they are fair in their price and also support the plantation owner with technical assistance.

“My brand of coffee is called Café Goa, and my farm is called Fazenda Goa,” says Moniz. His message for young Goans is clear. “In agriculture,” he says, “you’ve got to relate to the crop. Plan on doing something that you love doing, and your work will become leisure with a passion. Take into account the community who will benefit from your crop, and let that decide the profitability of your initiative.”

Moniz is now thinking about his next project, which he calls the ‘Curtorim Project’. “Even though I have been in Brazil for 45 years and love this country, I miss India and Goa in a big way. I would like to do something for my beautiful village, Curtorim. I have this simple agricultural project in mind which I would like to start implementing in 2023. The project consists of encouraging each family in Curtorim to have six very important and crucial plants in their backyards. These plants will give each family a supplement to the daily nutrients: drumstick (Moringa oleifera), grapes, Acerola cherry (Malpighia emarginata), tapioca (Manihot esculenta), coffee (Robusta) and tabebuia (a beautiful flowering tree, food for the soul),” he says.