For a holistic evaluation of India’s hard and long struggle for freedom from British imperialism, the nation needs to remember the crucial role of many unsung heroes and exemplary expatriate Indians

By Samudra Roy Chowdhury

This year, when Indians are busy passionately celebrating Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav, let me ask a simple question. How much do we know about the freedom struggle of India in other corners of the world? How many of us know that we were on the verge of attaining independence more than three decades before we actually became an independent nation and of the role of expatriates in it? Do we still see it through the monochromatic lens of non-violent movements that we have been taught in our schools or have we enriched our knowledge about several armed movements which immensely contributed towards our freedom from colonial rule?

Thousands of freedom fighters were imprisoned in the dreaded Andamans’ Cellular Jail by the British regime, many were hanged, many were killed in shootouts, 30,000-plus INA (Indian National Army or Azad Hind Fauj) soldiers died fighting against the British Army, many hundreds died during Army and Navy revolts thereafter. How much do we know about them? I am sure many among you would not be knowing much about these lesser-known or often forgotten chapters of our freedom struggle for we are being fed that India won freedom by spinning yarns on the supreme guidance of a Mahatma.

Long History of Armed Rebellion

I am not going to talk about details of all such events. I will focus primarily on the contribution of Indian expatriates in foreign lands, during the turbulent political climate of World War I, in the light of the Ghadar Movement and the Hindu-German Conspiracy.

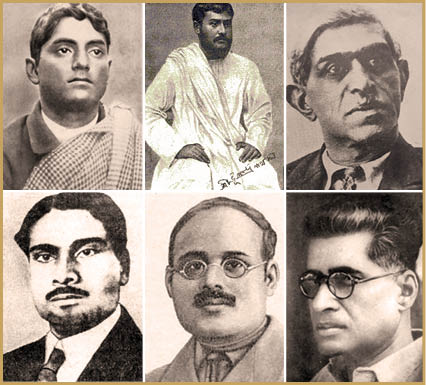

Long before Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s Great Escape during WW II from house arrest in Calcutta and his reaching out to Nazi Germany for support for India’s freedom, we had a long history of armed rebellion as part of the struggle for freedom. The army (Azad Hind Fauj) that Netaji led during WW II against the British Empire was founded by another great exiled nationalist, Rash Behari Bose, in Japan. He had to flee to Japan in 1915 after the British administration foiled his attempt at insurrection in the British Indian Army. During WW II, Rash Behari Bose convinced Japan’s government to support India’s freedom movement, formed the INA and passed the resolution in the second conference of the Indian Independence League (IIL) to invite Subhas Bose to take charge of it. Earlier, in 1912, one of the greatest Indian revolutionaries, Jatindranath Mukherjee aka Bagha Jatin met the German Crown Prince in Calcutta and secured his promise to support the Indian revolutionaries with money and arms if a war broke out between England and Germany. By that time, Bagha Jatin and his organization, Jugantar, had sent multiple revolutionaries to foreign lands, especially Europe, the US and Canada, for higher studies and also with a secret intent to learn military tactics and explosives manufacturing, and build public opinion in favour of India’s freedom.

Expatriate Connection

Two such notable leaders were Tarak Nath Das and Bhupendranath Datta (younger brother of Swami Vivekananda). Datta finished his master’s from Brown University in Rhode Island, US. He later worked closely with Ghadar leaders and went to Germany during WW I to take part in revolutionary activities. Das went to the University of California in Berkeley and later to the Georgetown University, from where he earned his PhD. Das founded the South Asian magazine, Free Hindustan, that eventually became a platform to raise a voice against British rule. He also worked very closely with Lala Har Dayal, who was one of the founders and key members of the Ghadar Party.

“Dr Tarak Nath Das, assisted by Guran Ditt Kumar, Harnam Singh, Professor Suren Bose, and after six years of zealous endeavour, reunited some Indian migrants in North America, arousing their patriotic sensibility and informing them about their rights in the country they chose to live in. This organised effort culminated with the formation of the Ghadar Party. Dr Das, with his intellectual foresight, saw the necessity of a thinker like Har Dayal to create a revolutionary movement. That was the genesis of Ghadar,” explained Dr Prithwindranath Mukherjee, a renowned historian and Padma Shri recipient. He also happens to be the grandson of Bagha Jatin. Anti-British sentiment among Indian expatriates was rising in the US and Canada during the second decade of the last century. The Komagata Maru incident in 1914 charged up the expatriate Indians even more. A group of people from British India tried to immigrate to Canada in April 1914 and travelled to Canada aboard the Japanese steamship, Komagata Maru. But most were denied entry into Canada, and they were forced to return to Calcutta. Anti-Asian lobbies in Canada and the US were so opposed to Chinese, Japanese and other South Asian immigration that Canada stopped immigration from India in 1908, which was followed by the US in 1910. Gross mistreatment of the passengers on Komagata Maru by the Canadian administration and then by the British police upon their return to Calcutta caused further uproar among overseas Indian communities, especially Punjabis. Before delving into the story of how India came closer to independence during World War I, there is a need to mention one more exemplary exiled nationalist – Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, aka Chatto, was the brother of Sarojini Naidu. Unfortunately, Mrs Naidu disassociated herself from her brother due to Virendranath’s anti-colonial activities and wrote a letter of indignation to the British authorities, stating that her brother had become wayward. Virendranath went to London to study law. He became actively involved in anti-imperialistic activities along with German, Italian and French participants. Later, Chatto built his network in Germany and made an agreement on a 15-point treaty – known as Plan Zimmermann – with the German government. Arthur Zimmermann was the State Secretary for Foreign Affairs in Germany then. That plan finally ensured the arms and money supply that the Crown Prince of Germany had promised to Bagha Jatin. He eventually became one of the most hunted men by Scotland Yard. The Kaiser himself sent a message via Indian revolutionaries to the then German ambassador in Washington, Von Bernstorff, to sanction funds to help an insurrection in India.

German consulates in New York, Chicago and San Francisco supplied money and facilities to Indian revolutionaries who were rushing to join Chatto in Berlin. In the meantime, Ghadarites in the United States, Canada and Germany made an alliance with Jugantar leaders, under the leadership of Bagha Jatin. Thousands of Ghadarites started coming back to India to join the revolution.

Stirrings of the Rebellion

Under Bagha Jatin’s instructions, Rash Behari Bose began establishing contacts in various military cantonments of North India (Benaras, Nainital, Lahore, Peshawar, etc.) and also in Fort William in Calcutta. V.G. Pingle and Sachindranath Sanyal also became active in triggering defection in the British Indian Army, under the leadership of Bagha Jatin. The revolutionaries got allegiance from multiple units like 93rd Burma Regiment and 16th Rajput Rifles. Bagha Jatin involved his right-hand man, Narendranath Bhattacharya aka M.N. Roy, who later founded the Communist Party of India and the Mexican Communist Party, in the mission. On December 7, 1914, Bernstorff acknowledged the purchase of 11,000 rifles, four million cartridges, 250 Mauser pistols, and 500 revolvers with ammunition, for India. On January 9, 1915, Von Oppenheim of the German Foreign Office confirmed that 30,000 rifles and 5,000 automatic pistols were ready to be dispatched to India.

Failed Attempt

A plan was made in the Berlin Committee to send an army, formed of imprisoned Indian soldiers in Turkey and the Middle East, to enter India through Peshawar, while Ghadar leaders under Tarak Nath Das would storm through Thailand and Burma, reach Calcutta, seize Fort William, and join the invading army at Peshawar. The revolution was ready to be launched and India was inches away from a well-fought-for independence. Bagha Jatin, the Commander-in-Chief of that operation, scheduled February 21, 1915 as the date of the insurrection. It is also known as the February Plot. Unfortunately, the plan was sabotaged by multiple betrayals and two of them proved vital. A police agent named Kirpal Singh passed the information to the British police. He was recruited by the Punjab CID to infiltrate the revolutionaries. Upon being informed, Rash Behari Bose tried to advance the insurrection to February 19. But even that date was leaked. Bose had to flee to Japan. Revolts by multiple army regiments like the Baluchi Regiment, 26th Punjab, 7th Rajput, 130th Baluch, and 24th Jat Artillery were foiled.

Two other expatriates, Pingle and Kartar Singh Sarabha, who returned from the United States to lead segments of the holistic armed rebellion, put their last efforts into starting the mutiny in the 12th Cavalry regiment in Meerut. Both were eventually captured and tried in the Lahore Conspiracy Case and hanged on November 16, 1915. The British regime brutally suppressed the movement by hanging 46 Ghadarites and sending hundreds of them to life imprisonment. “Even when, under the joint direction of Jatin and Rash Behari, the All-India uprising of February 21, 1915 failed, a number of regiments participated in the revolutionary project: the 12th and 23rd Cavalry, the 128th Pioneers, the 7th and 14th Rajputs inside India; the 5th Light Infantry and the Malaya States Guides in Singapore. The last two regiments maintained a one-week state of siege, after having occupied the Singapore fort,” wrote Dr. Prithwindranath Mukherjee in The Intellectual Roots of India’s Freedom Struggle (1893-1918).

Rebounding from Setback

Even after that major setback, Bagha Jatin didn’t waver from his commitment to free India by taking advantage of the World War I situation. Germany had already planned to send over 4,000 rifles and around one million cartridges to India, using two German vessels, Annie Larsen and SS Maverick. At that time the United States had not joined the war and was maintaining neutrality. The Annie Larsen left San Diego port in the US in February 1915 in order to meet with SS Maverick and offload the shipment to be dispatched to the Indian revolutionaries. But the British Secret Service had learned of the plot and the Royal Navy cruiser, H.M.S. Newcastle, shadowed the Annie Larsen throughout. After almost five months of failed attempts, when the Annie Larsen returned to the US west coast port city of Hoquiam on June 29, 1915, the US Customs officials at Grays Harbor seized the ship, which was found to be carrying arms and ammunition in violation of neutrality laws. This made the British Foreign Office even more vigilant and it expanded its network in America and Canada. It started actively pursuing Indian students and other expatriates in the United States. It took the help of the Czech counter-espionage network run by E.V. Voska and planted a Czech refugee as a spy, disguised as a housekeeper, in the apartment of some Indian nationalists in New York City. An Irish double agent and an Indian agent codenamed ‘C’ passed valuable information to the British. ‘C’ is believed to have been a wayward Jugantar member, Chandrakanta Chakrabarti.

In the meantime, Bagha Jatin and members of Jugantar planned to receive another shipment of 9,000 firearms and over four million pieces of ammunition from German ships S Henry and SS Djember, using the East Asian route. They were planning another insurrection on December 25, 1915, the Christmas Day Plot.

The Final Battle

The plan was to take control of Fort William in Calcutta and execute simultaneous revolts by Ghadarites in Burma and Siam. The United Kingdom had already dispatched a majority of the British Indian forces outside India to fight World War I. A smaller number of regiments were there to guard India. Bagha Jatin knew this was the right opportunity to defeat them. He sent M.N. Roy to Batavia (part of current-day Indonesia) to implement the plan of getting German ammunition from the SS Djember. As Roy later recounted, “The plan was to use German ships interned in a port at the northern tip of Sumatra to storm the Andaman Islands and free and arm the prisoners there and land the army of liberation on the Orissa coast. The ships were armoured, as many big German vessels were ready for wartime use.” Orissa’s Balasore coast was selected for the final arms drop. But the acts of the Czech spy in the United States, and of the Baltic-German double agent codenamed ‘Oren’ in Batavia foiled that plan as well. The Berlin Committee had to abandon the shipment. Not knowing about the betrayal, Bagha Jatin with his followers had already arrived at the Balasore coast, only to be countered by the Deputy Commissioner of Calcutta Police, Charles Tegart, on September 9, 1915. They fought a heroic gun-battle that lasted 75 minutes; some of the revolutionaries died and Bagha Jatin was captured, mortally wounded. He died the next day in a Balasore hospital. Before the battle, his followers had told him to flee. He had said in Bengali, “Amra morbo, jagat jagbe” or “We will die to awaken the nation”. The Ghadar movement maintained its momentum for some time. The Berlin Committee (or Indian Independence Committee) was successful in forming a provisional Indian government in exile, in Kabul on December 1, 1915, with support from the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria). Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh served as the president in that government. In November 1917, the United States started the Hindu-German Conspiracy Trial in the district court of San Francisco. It lasted five months and many of the Ghadar leaders, among other Indian revolutionaries, were convicted on the charge of waging military action against Britain while taking advantage of American neutrality during the initial phase of World War I.

The plan was to take control of Fort William in Calcutta and execute simultaneous revolts by Ghadarites in Burma and Siam. The United Kingdom had already dispatched a majority of the British Indian forces outside India to fight World War I. A smaller number of regiments were there to guard India. Bagha Jatin knew this was the right opportunity to defeat them. He sent M.N. Roy to Batavia (part of current-day Indonesia) to implement the plan of getting German ammunition from the SS Djember. As Roy later recounted, “The plan was to use German ships interned in a port at the northern tip of Sumatra to storm the Andaman Islands and free and arm the prisoners there and land the army of liberation on the Orissa coast. The ships were armoured, as many big German vessels were ready for wartime use.” Orissa’s Balasore coast was selected for the final arms drop. But the acts of the Czech spy in the United States, and of the Baltic-German double agent codenamed ‘Oren’ in Batavia foiled that plan as well. The Berlin Committee had to abandon the shipment. Not knowing about the betrayal, Bagha Jatin with his followers had already arrived at the Balasore coast, only to be countered by the Deputy Commissioner of Calcutta Police, Charles Tegart, on September 9, 1915. They fought a heroic gun-battle that lasted 75 minutes; some of the revolutionaries died and Bagha Jatin was captured, mortally wounded. He died the next day in a Balasore hospital. Before the battle, his followers had told him to flee. He had said in Bengali, “Amra morbo, jagat jagbe” or “We will die to awaken the nation”. The Ghadar movement maintained its momentum for some time. The Berlin Committee (or Indian Independence Committee) was successful in forming a provisional Indian government in exile, in Kabul on December 1, 1915, with support from the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria). Raja Mahendra Pratap Singh served as the president in that government. In November 1917, the United States started the Hindu-German Conspiracy Trial in the district court of San Francisco. It lasted five months and many of the Ghadar leaders, among other Indian revolutionaries, were convicted on the charge of waging military action against Britain while taking advantage of American neutrality during the initial phase of World War I.

Not Just a Failure

It may seem that the Hindu-German Conspiracy failed to liberate India. But we should remember that every revolutionary activity snowballs into another. The next generation of revolutionaries like Bhagat Singh was highly influenced by that struggle. When Jugantar organised Bagha Jatin’s eighth death anniversary commemoration from Calcutta to Lahore on September 9, 1923, the young Bhagat Singh participated in it. And the feeling of patriotism and nationalism that the rebellion fostered by Bagha Jatin with passionate support from expatriate leaders spawned within the British Indian Army during WW I can be traced to WW II with the formation of the INA/Azad Hind Fauj. I think this feeling culminated during the Naval Revolt of 1946. Even though the Naval Revolt is unfortunately not given its due in our mainstream history, it was significant. In fact, there were multiple revolts in the Royal Indian Navy between 1943 and 1945. During the 1946 revolt, multiple army barracks supported the Navy revolt. In one instance, when British army officials ordered the Gurkha regiment in Karachi to fire on the navy personnel, they refused and the British realised that they had lost control over the Indian armed forces, and that it was time to leave India. In a seminar in 1967, on the 20th anniversary of Independence, the then British High Commissioner, John Freeman, marked the Naval Revolt as one of the key factors in Britain leaving India. He said, “The British were petrified of a repeat of the 1857 Mutiny, since this time they feared they would be slaughtered to the last man.”

Do We Remember?

Known as the Hindu-German Conspiracy, the above described armed rebellion envisaged by Bagha Jatin was one of the most significant efforts against the imperial British Empire that took us to the verge of freedom, three decades before we actually got it. Jatin’s adversary, the Commissioner of Police, Charles Tegart, later said, “Bagha Jatin, the Bengali revolutionary, is one of the most selfless political workers in India. If an army could be raised or arms could reach an Indian port, the British would lose the war.” It was a war of independence where expatriate Indians played a critical part. However, the immense sacrifice of Bagha Jatin and his group of committed revolutionaries, which included a few exemplary people from the Indian diaspora, has been neglected by our mainstream history and consequently has been long forgotten in our popular culture. This is our collective shame as a nation.

(The writer is an IT professional, passionate about Indian history and the founder of www.indicvoices.com)

(The writer is an IT professional, passionate about Indian history and the founder of www.indicvoices.com)

Contact Us

M/s Template Media LLP

(Publisher of PRAVASI INDIANS),

34A/K-Block, Saket,

New Delhi-110017

www.pravasindians.com

Connect with us at:

Mobile: +91 98107 66339

Email: info@pravasindians.com

Copyright 2023@ Template Media LLP. All Rights Reserved.